Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjectivity, imagination, and appreciation of nature in society and culture during the Age of Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution.

Romanticists rejected the social conventions of the time in favor of a moral outlook known as individualism. They argued that passion and intuition were crucial to understanding the world, and that beauty wasn't purely intellectual but rather something that evokes a strong emotional response. With this philosophical foundation, the Romanticists elevated a number of key themes to which they were deeply committed: a reverence for nature and the supernatural, an idealization of the past as a nobler era, a fascination with the exotic and the mysterious, and a celebration of the heroic and the sublime.

The Romanticist movement had a particular fondness for the Middle Ages, which to them represented an era of chivalry, heroism, and a more organic relationship between humans and their environment. This idealization contrasted sharply with the values of their contemporary industrial society, which they considered alienating for its economic materialism and environmental degradation. The movement's illustration of the Middle Ages was a key theme in debates, with allegations that Romanticist portrayals often overlooked the downsides of medieval life.

The consensus is that Romanticism peaked from 1800 until 1850. Romanticism was a complex movement, with a variety of viewpoints that permeated Western civilization across the globe. The movement and its opposing ideologies mutually shaped each other as time went on. Even after its end, Romantic thought exerted a sweeping influence on art and music, cinema, speculative fiction, philosophy, politics, and environmentalism that has endured into the present day.

The movement is the reference for the modern notion of "romanticization" and the act of "romanticizing" something.

Background[edit]

Timeline[edit]

For most of the Western world, Romanticism was at its peak from approximately 1800 to 1850. The period typically called Romantic varies greatly between different countries and different artistic media or areas of thought. Margaret Drabble described it in literature as taking place "roughly between 1770 and 1848",[1] and few dates much earlier than 1770 will be found. In English literature, M. H. Abrams placed it between 1789, or 1798, this latter a very typical view, and about 1830, perhaps a little later than some other critics.[2] Others have proposed 1780–1830.[3] In other fields and other countries the period denominated as Romantic can be considerably different; musical Romanticism, for example, is generally regarded as only having ceased as a major artistic force as late as 1910, but in an extreme extension the Four Last Songs of Richard Strauss are described stylistically as "Late Romantic" and were composed in 1946–48.[4] However, in most fields the Romantic period is said to be over by about 1850, or earlier.

The first Romantic ideas arose from an earlier German Counter-Enlightenment movement called Sturm und Drang (German: "Storm and Stress"). This movement directly criticized the Enlightenment's position that humans can fully comprehend the world through rationality alone, suggesting that intuition and emotion are key components of insight and understanding.[5] Published in 1774, "The Sorrows of Young Werther" by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe began to shape the Romanticist movement and its ideals. The events and ideologies of the French Revolution were also direct influences on the movement; many early Romantics throughout Europe sympathized with the ideals and achievements of French revolutionaries.[6]

The early period of the Romantic era was a time of war, with the French Revolution (1789–1799) followed by the Napoleonic Wars until 1815. These wars, along with the political and social turmoil that went along with them, served as the background for Romanticism.[7] The key generation of French Romantics born between 1795 and 1805 had, in the words of one of their number, Alfred de Vigny, been "conceived between battles, attended school to the rolling of drums".[8] According to Jacques Barzun, there were three generations of Romantic artists. The first emerged in the 1790s and 1800s, the second in the 1820s, and the third later in the century.[9]

A confluence of circumstances led to Romanticism's decline in the mid-19th century, including (but not limited to) the rise of Realism and Naturalism, Charles Darwin's publishing of the Origin of Species, the transition from widespread revolution in Europe to a more conservative climate, and a shift in public consciousness to the immediate impact of technology and urbanization on the working class. By World War I, Romanticism was overshadowed by new cultural, social, and political movements, many of them hostile to the perceived illusions and preoccupations of the Romantics.

Though the High Romantic Era is considered to have ended around 1850, a "Late Romantic" period and "Neoromantic" revivals are also discussed. These extensions of the movement are characterized by a resistance to the increasingly experimental and abstract forms that culminated in modern art, and the expansion and deconstruction of traditional tonal harmony in music. They continued the Romantic ideal, stressing depth of emotion in art and music while showcasing technical mastery in a mature Romantic style. By the time of World War I though, the cultural and artistic climate had changed to such a degree that Romanticism essentially dispersed into subsequent movements. The final Late Romanticist figures to maintain the Romantic ideals died in the 1940s. Though they were still widely respected, they were seen as anachronisms at that point.

However, Romanticism has had a lasting impact on Western civilization, and many works of art, music, and literature that embody the Romantic ideals have been made after the end of the Romantic Era. The movement's advocacy for nature appreciation is cited as an influence for current nature conservation efforts. The majority of film scores from the Golden Age of Hollywood were written in the lush orchestral Romantic style, and this genre of orchestral cinematic music is still often seen in films of the 21st century. The philosophical underpinnings of the movement have influenced modern political theory, both among liberals and conservatives.

Context and place in history[edit]

Romanticism was partly a reaction to the Industrial Revolution,[10] and the prevailing ideology of the Age of Enlightenment, especially the scientific rationalization of Nature.[11] The movement's ideals were embodied most strongly in the visual arts, music, and literature; it also had a major impact on historiography,[12] education,[13] chess, social sciences, and the natural sciences.[14]

The more precise characterization and specific definition of Romanticism has been the subject of debate in the fields of intellectual history and literary history throughout the 20th century, without any great measure of consensus emerging. Its relationship to the French Revolution, which began in 1789 in the very early stages of the period, is clearly important, but highly variable depending on geography and individual reactions.

Romanticism had a significant and complex effect on politics: Romantic thinking influenced conservatism, liberalism, radicalism, and nationalism.[15][16] Most Romantics can be said to be broadly progressive in their views, but a considerable number always had, or developed, a wide range of conservative views,[17] and nationalism was in many countries strongly associated with Romanticism.

Characteristics[edit]

Individualism and emotion[edit]

Romanticism embodied a new and restless spirit, seeking violently to burst through old and cramping forms, a nervous preoccupation with perpetually changing inner states of consciousness, a longing for the unbounded and the indefinable, for perpetual movement and change, an effort to return to the forgotten sources of life, a passionate effort at self-assertion both individual and collective, a search after means of expressing an unappeasable yearning for unattainable goals.

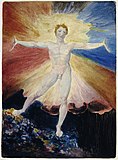

Romanticism placed the highest importance on the freedom of the artists to authentically express their sentiments and ideas. The movement prioritized the artist's unique, individual imagination above the strictures of classical form, and emphasized intense emotion as an authentic source of aesthetic experience. It granted a new importance to experiences of sympathy, awe, wonder, and terror, in part by naturalizing such emotions as responses to the "beautiful" and the "sublime".[19][20]

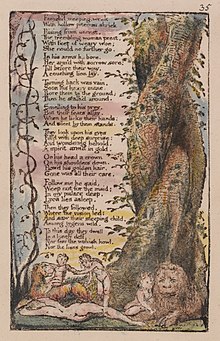

Romantics like the German painter Caspar David Friedrich believed that an artist's emotions should dictate their formal approach; Friedrich went as far as declaring that "the artist's feeling is his law".[21] The Romantic poet William Wordsworth, thinking along similar lines, wrote that poetry should begin with "the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings", which the poet then "recollect[s] in tranquility", enabling the poet to find a suitably unique form for representing such feelings.[22]

The Romantics never doubted that emotionally motivated art would find suitable, harmonious modes for expressing its vital content—if, that is, the artist steered clear of moribund conventions and distracting precedents. Samuel Taylor Coleridge and others thought there were natural laws the imagination of born artists followed instinctively when these individuals were, so to speak, "left alone" during the creative process.[23] These "natural laws" could support a wide range of different formal approaches: as many, perhaps, as there were individuals making personally meaningful works of art. Many Romantics believed that works of artistic genius were created "ex nihilo", "from nothing", without recourse to existing models.[24][25][26] This idea is often called "romantic originality".[27] The translator and prominent Romantic August Wilhelm Schlegel argued in his Lectures on Dramatic Arts and Letters that the most valuable quality of human nature is its tendency to diverge and diversify.[28]

Romantic literature was frequently written in a distinctive, personal "voice". As critic M. H. Abrams has observed, "much of romantic poetry invited the reader to identify the protagonists with the poets themselves."[29] This quality in Romantic literature, in turn, influenced the approach and reception of works in other media; it has seeped into everything from critical evaluations of individual style in painting, fashion, and music, to the auteur movement in modern filmmaking.

Nature[edit]

Romantic artists also shared a strong belief in the importance and inspirational qualities of Nature. Romantics were distrustful of cities and social conventions. They deplored Restoration and Enlightenment Era artists who were largely concerned with depicting and critiquing social relations, thereby neglecting the relationship between people and Nature. Romantics generally believed a close connection with Nature was beneficial for human beings, especially for individuals who broke off from society in order to encounter the natural world by themselves.

Nationalism[edit]

One of Romanticism's key ideas and most enduring legacies is the assertion of nationalism, which became a central theme of Romantic art and political philosophy. From the earliest parts of the movement, with their focus on development of national languages and folklore, and the importance of local customs and traditions, to the movements that would redraw the map of Europe and lead to calls for self-determination of nationalities, nationalism was one of the key vehicles of Romanticism, its role, expression and meaning. One of the most important functions of medieval references in the 19th century was nationalist. Popular and epic poetry were its workhorses. This is visible in Germany and Ireland, where underlying Germanic or Celtic linguistic substrates dating from before the Romanization-Latinization were sought out.

Early Romantic nationalism was strongly inspired by Rousseau, and by the ideas of Johann Gottfried von Herder, who in 1784 argued that the geography formed the natural economy of a people, and shaped their customs and society.[30]

The nature of nationalism changed dramatically, however, after the French Revolution with the rise of Napoleon, and the reactions in other nations. Napoleonic nationalism and republicanism were, at first, inspirational to movements in other nations: self-determination and a consciousness of national unity were held to be two of the reasons why France was able to defeat other countries in battle. But as the French Republic became Napoleon's Empire, Napoleon became not the inspiration for nationalism, but the object of its struggle. In Prussia, the development of spiritual renewal as a means to engage in the struggle against Napoleon was argued by, among others, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, a disciple of Kant. The word Volkstum, or nationality, was coined in German as part of this resistance to the now conquering emperor.

Other themes and motifs[edit]

- Nostalgia

- Romantics stressed the nobility of folk art and ancient cultural practices, but also championed radical politics, unconventional behavior, and authentic spontaneity. In contrast to the rationalism and classicism of the Enlightenment, Romanticism revived medievalism[31] and juxtaposed a pastoral conception of a more "authentic" European past with a highly critical view of recent social changes, including urbanization, brought about by the Industrial Revolution.

- The Romantic hero

- Romanticism lionized the achievements of "heroic" individuals – especially artists, who began to be represented as cultural leaders (one Romantic luminary, Percy Bysshe Shelley, described poets as the "unacknowledged legislators of the world" in his "Defence of Poetry").

Literature[edit]

In literature, Romanticism found recurrent themes in the evocation or criticism of the past, the cult of "sensibility" with its emphasis on women and children, the isolation of the artist or narrator, and respect for nature. Furthermore, several romantic authors, such as Edgar Allan Poe, Charles Maturin and Nathaniel Hawthorne, based their writings on the supernatural/occult and human psychology. Romanticism tended to regard satire as something unworthy of serious attention, a view still influential today.[32] The Romantic movement in literature was preceded by the Enlightenment and succeeded by Realism.

Some authors cite 16th-century poet Isabella di Morra as an early precursor of Romantic literature. Her lyrics covering themes of isolation and loneliness, which reflected the tragic events of her life, are considered "an impressive prefigurement of Romanticism",[33] differing from the Petrarchist fashion of the time based on the philosophy of love.

The precursors of Romanticism in English poetry go back to the middle of the 18th century, including figures such as Joseph Warton (headmaster at Winchester College) and his brother Thomas Warton, Professor of Poetry at Oxford University.[34] Joseph maintained that invention and imagination were the chief qualities of a poet. The Scottish poet James Macpherson influenced the early development of Romanticism with the international success of his Ossian cycle of poems published in 1762, inspiring both Goethe and the young Walter Scott. Thomas Chatterton is generally considered the first Romantic poet in English.[35] Both Chatterton and Macpherson's work involved elements of fraud, as what they claimed was earlier literature that they had discovered or compiled was, in fact, entirely their own work. The Gothic novel, beginning with Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto (1764), was an important precursor of one strain of Romanticism, with a delight in horror and threat, and exotic picturesque settings, matched in Walpole's case by his role in the early revival of Gothic architecture. Tristram Shandy, a novel by Laurence Sterne (1759–67), introduced a whimsical version of the anti-rational sentimental novel to the English literary public.

Architecture[edit]

Romantic architecture appeared in the late 18th century in a reaction against the rigid forms of neoclassical architecture. Romantic architecture reached its peak in the mid-19th century, and continued to appear until the end of the 19th century. It was designed to evoke an emotional reaction, either respect for tradition or nostalgia for a bucolic past. It was frequently inspired by the architecture of the Middle Ages, especially Gothic architecture, it was strongly influenced by romanticism in literature, particularly the historical novels of Victor Hugo and Walter Scott. It sometimes moved into the domain of eclecticism, with features assembled from different historic periods and regions of the world.[36]

Gothic Revival architecture was a popular variant of the romantic style, particularly in the construction of churches, Cathedrals, and university buildings. Notable examples include the completion of Cologne Cathedral in Germany, by Karl Friedrich Schinkel. The cathedral's construction began in 1248, but was halted in 1473. The original plans for the façade were discovered in 1840, and it was decided to recommence. Schinkel followed the original design as much as possible, but he also used modern construction technology, including an iron frame for the roof. The building was finished in 1880.[37]

In Britain, notable examples include the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, a romantic version of traditional Indian architecture by John Nash (1815–1823), and the Houses of Parliament in London, built in a Gothic revival style by Charles Barry between 1840 and 1876.[38]

In France, one of the earliest examples of romantic architecture is the Hameau de la Reine, the small rustic hamlet created at the Palace of Versailles for Queen Marie Antoinette between 1783 and 1785 by the royal architect Richard Mique with the help of the romantic painter Hubert Robert. It consisted of twelve structures, ten of which still exist, in the style of villages in Normandy. It was designed for the Queen and her friends to amuse themselves by playing at being peasants, and included a farmhouse with a dairy, a mill, a boudoir, a pigeon loft, a tower in the form of a lighthouse from which one could fish in the pond, a belvedere, a cascade and grotto, and a luxuriously furnished cottage with a billiard room for the Queen.[39]

French romantic architecture in the 19th century was strongly influenced by two writers; Victor Hugo, whose novel The Hunchback of Notre Dame inspired a resurgence in interest in the Middle Ages; and Prosper Mérimée, who wrote celebrated romantic novels and short stories and was also the first head of the commission of Historic Monuments in France, responsible for publicizing and restoring (and sometimes romanticizing) many French cathedrals and monuments desecrated and ruined after the French Revolution. His projects were carried out by the architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. These included the restoration (sometimes creative) of the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris, the fortified city of Carcassonne, and the unfinished medieval Château de Pierrefonds.[37][40]

The romantic style continued in the second half of the 19th century. The Palais Garnier, the Paris opera house designed by Charles Garnier was a highly romantic and eclectic combination of artistic styles. Another notable example of late 19th century romanticism is the Basilica of Sacré-Cœur by Paul Abadie, who drew upon the model of Byzantine architecture for his elongated domes (1875–1914).[38]

-

Hameau de la Reine, Palace of Versailles (1783–1785)

-

Cologne Cathedral (1840–80)

-

Grand Staircase of the Paris Opera by Charles Garnier (1861–75)

-

Basilica of Sacré-Cœur by Paul Abadie (1875–1914)

Visual arts[edit]

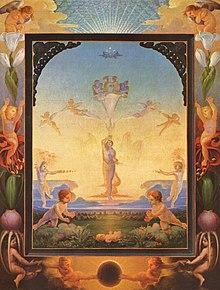

Romanticism in the visual arts, originating in the 1760s, marked a shift towards depicting wild landscapes and dramatic scenes, reflecting a departure from classical artistic norms. This movement emphasized the sublime beauty of nature, the intensity of human emotions, and the glorification of the past, often through the lens of national identity and historical events.

Romantic art spread across Europe, gradually influencing various forms of artistic expression, and later resonated in America where artists incorporated these themes into portrayals of the unique American landscape. Its influence eventually spread globally, shaping various art forms and inspiring artists to express a more profound, emotional response to the natural world and societal changes. Romantic art highlighted the power of the individual perspective and the universal human experience, resonating across different cultures and leading to lasting impacts on artistic expression worldwide.

- Gallery

Old Age (1842)

Music[edit]

The term "Romanticism" when applied to music has come to imply the period roughly from 1800 until 1850, or else until around 1900. Musical Romanticism is predominantly a German phenomenon—so much so that one respected French reference work defines it entirely in terms of "The role of music in the aesthetics of German romanticism".[41] Another French encyclopedia holds that the German temperament generally "can be described as the deep and diverse action of romanticism on German musicians", and that there is only one true representative of Romanticism in French music, Hector Berlioz, while in Italy, the sole great name of musical Romanticism is Giuseppe Verdi, "a sort of [Victor] Hugo of opera, gifted with a real genius for dramatic effect". Similarly, in his analysis of Romanticism and its pursuit of harmony, Henri Lefebvre posits that, "But of course, German romanticism was more closely linked to music than French romanticism was, so it is there we should look for the direct expression of harmony as the central romantic idea."[42] Nevertheless, the huge popularity of German Romantic music led, "whether by imitation or by reaction", to an often nationalistically inspired vogue amongst Polish, Hungarian, Russian, Czech, and Scandinavian musicians, successful "perhaps more because of its extra-musical traits than for the actual value of musical works by its masters".[43]

In the contemporary music culture, the romantic musician followed a public career depending on sensitive middle-class audiences rather than on a courtly patron, as had been the case with earlier musicians and composers. Public persona characterized a new generation of virtuosi who made their way as soloists, epitomized in the concert tours of Paganini and Liszt, and the conductor began to emerge as an important figure, on whose skill the interpretation of the increasingly complex music depended.[44]

- Origins of applying the term "Romanticism" to music

Ludwig van Beethoven, painted by Joseph Karl Stieler, 1820 - One of the first significant applications of the term to music was in 1789, in the Mémoires by the Frenchman André Grétry, but it was E. T. A. Hoffmann who established the principles of musical romanticism, in a lengthy review of Ludwig van Beethoven's Fifth Symphony published in 1810, and an 1813 article on Beethoven's instrumental music. In the first of these essays Hoffmann traced the beginnings of musical Romanticism to the later works of Haydn and Mozart. It was Hoffmann's fusion of ideas already associated with the term "Romantic", used in opposition to the restraint and formality of Classical models, that elevated music, and especially instrumental music, to a position of pre-eminence in Romanticism as the art most suited to the expression of emotions. It was also through the writings of Hoffmann and other German authors that German music was brought to the center of musical Romanticism.[45]

-

Felix Mendelssohn, 1839

-

Robert Schumann, 1839

-

Franz Liszt, 1847

-

Daniel Auber, c. 1868

-

Hector Berlioz by Gustave Courbet, 1850

-

Giovanni Boldini, Portrait of Giuseppe Verdi, 1886

-

Richard Wagner, c. 1870s

-

Gustav Mahler, 1896

Outside the arts[edit]

- Sciences

- The Romantic movement affected most aspects of intellectual life, and Romanticism and science had a powerful connection, especially in the period 1800–1840. Many scientists were influenced by versions of the Naturphilosophie of Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and others, and without abandoning empiricism, sought in their work to uncover what they tended to believe was a unified and organic Nature. The English scientist Sir Humphry Davy, a prominent Romantic thinker, said that understanding nature required "an attitude of admiration, love and worship, [...] a personal response".[46] He believed that knowledge was only attainable by those who truly appreciated and respected nature. Self-understanding was an important aspect of Romanticism. It had less to do with proving that man was capable of understanding nature (through his budding intellect) and therefore controlling it, and more to do with the emotional appeal of connecting himself with nature and understanding it through a harmonious co-existence.[47]

- Historiography

- History writing was very strongly, and many would say harmfully, influenced by Romanticism.[48] In England, Thomas Carlyle was a highly influential essayist who turned historian; he both invented and exemplified the phrase "hero-worship",[49] lavishing largely uncritical praise on strong leaders such as Oliver Cromwell, Frederick the Great and Napoleon. Romantic nationalism had a largely negative effect on the writing of history in the 19th century, as each nation tended to produce its own version of history, and the critical attitude, even cynicism, of earlier historians was often replaced by a tendency to create romantic stories with clearly distinguished heroes and villains.[50] Nationalist ideology of the period placed great emphasis on racial coherence, and the antiquity of peoples, and tended to vastly overemphasize the continuity between past periods and the present, leading to national mysticism. Much historical effort in the 20th century was devoted to combating the romantic historical myths created in the 19th century.

- Theology

- To insulate theology from scientism or reductionism in science, 19th-century post-Enlightenment German theologians developed a modernist or so-called liberal conception of Christianity, led by Friedrich Schleiermacher and Albrecht Ritschl. They took the Romantic approach of rooting religion in the inner world of the human spirit, so that it is a person's feeling or sensibility about spiritual matters that comprises religion.[51]

- Chess

- Romantic chess was the style of chess which emphasized quick, tactical maneuvers characterized by aesthetic beauty rather than long-term strategic planning, which was considered to be of secondary importance.[52] The Romantic era in chess is generally considered to have begun around the 18th century (although a primarily tactical style of chess was predominant even earlier),[53] and to have reached its peak with Joseph MacDonnell and Pierre LaBourdonnais, the two dominant chess players in the 1830s. The 1840s were dominated by Howard Staunton, and other leading players of the era included Adolf Anderssen, Daniel Harrwitz, Henry Bird, Louis Paulsen, and Paul Morphy. The "Immortal Game", played by Anderssen and Lionel Kieseritzky on 21 June 1851 in London—where Anderssen made bold sacrifices to secure victory, giving up both rooks and a bishop, then his queen, and then checkmating his opponent with his three remaining minor pieces—is considered a supreme example of Romantic chess.[54] The end of the Romantic era in chess is considered to be the 1873 Vienna Tournament where Wilhelm Steinitz popularized positional play and the closed game.

See also[edit]

|

Related terms

|

Opposing terms

|

Other

|

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ in her Oxford Companion article, quoted by Day, 1

- ^ Day, 1–5

- ^ Mellor, Anne; Matlak, Richard (1996). British Literature 1780–1830. NY: Harcourt Brace & Co./Wadsworth. ISBN 978-1-4130-2253-7.

- ^ Edward F. Kravitt, The Lied: Mirror of Late Romanticism Archived 2022-12-04 at the Wayback Machine (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1996): 47. ISBN 0-300-06365-2.

- ^ Hamilton, Paul (2016). The Oxford Handbook of European Romanticism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-19-969638-3.

- ^ Blechman, Max (1999). Revolutionary Romanticism: A Drunken Boat Anthology. San Francisco, CA: City Lights Books. pp. 84–85. ISBN 0-87286-351-4.

- ^ Greenblatt et al., Norton Anthology of English Literature, eighth edition, "The Romantic Period – Volume D" (New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc., 2006): [page needed]

- ^ Johnson, 147, inc. quotation

- ^ Barzun, 469

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica. "Romanticism. Retrieved 30 January 2008, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 13 October 2005. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ Casey, Christopher (October 30, 2008). ""Grecian Grandeurs and the Rude Wasting of Old Time": Britain, the Elgin Marbles, and Post-Revolutionary Hellenism". Foundations. Volume III, Number 1. Archived from the original on May 13, 2009. Retrieved 2014-05-14.

- ^ David Levin, History as Romantic Art: Bancroft, Prescott, and Parkman (1967)

- ^ Gerald Lee Gutek, A history of the Western educational experience (1987) ch. 12 on Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi

- ^ Ashton Nichols, "Roaring Alligators and Burning Tygers: Poetry and Science from William Bartram to Charles Darwin", Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 2005 149(3): 304–15

- ^ Morrow, John (2011). "Romanticism and political thought in the early 19th century" (PDF). In Stedman Jones, Gareth; Claeys, Gregory (eds.). The Cambridge History of Nineteenth-Century Political Thought. The Cambridge History of Political Thought. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University. pp. 39–76. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521430562. ISBN 978-0-511-97358-1. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ Guliyeva, Gunesh (2022-12-15). "Traces of Romanticism in the Creativity of Bahtiyar Vahabzade" (PDF). Metafizika (in Azerbaijani). 5 (4): 77–87. eISSN 2617-751X. ISSN 2616-6879. OCLC 1117709579. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-11-14. Retrieved 2022-10-14.

- ^ Day, 1–3; the arch-conservative and Romantic is Joseph de Maistre, but many Romantics swung from youthful radicalism to conservative views in middle age, for example Wordsworth. Samuel Palmer's only published text was a short piece opposing the Repeal of the corn laws.

- ^ Berlin, 92

- ^ Coleman, Jon T. (2020). Nature Shock: Getting Lost in America. Yale University Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-300-22714-7.

- ^ Barnes, Barbara A. (2006). Global Extremes: Spectacles of Wilderness Adventure, Endless Frontiers, and American Dreams. Santa Cruz: University of California Press. p. 51.

- ^ Novotny, 96

- ^ From the Preface to the 2nd edition of Lyrical Ballads, quoted Day, 2

- ^ Day, 3

- ^ Ruthven (2001) p. 40 quote: "Romantic ideology of literary authorship, which conceives of the text as an autonomous object produced by an individual genius."

- ^ Spearing (1987) quote: "Surprising as it may seem to us, living after the Romantic movement has transformed older ideas about literature, in the Middle Ages authority was prized more highly than originality."

- ^ Eco (1994) p. 95 quote: Much art has been and is repetitive. The concept of absolute originality is a contemporary one, born with Romanticism; classical art was in vast measure serial, and the "modern" avant-garde (at the beginning of this century) challenged the Romantic idea of "creation from nothingness", with its techniques of collage, mustachios on the Mona Lisa, art about art, and so on.

- ^ Waterhouse (1926), throughout; Smith (1924); Millen, Jessica Romantic Creativity and the Ideal of Originality: A Contextual Analysis, in Cross-sections, The Bruce Hall Academic Journal – Volume VI, 2010 PDF Archived 2016-03-14 at the Wayback Machine; Forest Pyle, The Ideology of Imagination: Subject and Society in the Discourse of Romanticism (Stanford University Press, 1995) p. 28.

- ^ Breckman, Warren (2008). European Romanticism: A Brief History with Documents. Rogers D. Spotswood Collection. (1st ed.). Boston: Bedford/St. Martins. ISBN 978-0-312-45023-6. OCLC 148859077.

- ^ Day 3–4; quotation from M.H. Abrams, quoted in Day, 4

- ^ Hayes, Carlton (July 1927). "Contributions of Herder to the Doctrine of Nationalism". The American Historical Review. 32 (4): 722–723. doi:10.2307/1837852. JSTOR 1837852.

- ^ Perpinya, Núria. Ruins, Nostalgia and Ugliness. Five Romantic perceptions of Middle Ages and a spoon of Game of Thrones and Avant-garde oddity Archived 2016-03-13 at the Wayback Machine. Berlin: Logos Verlag. 2014

- ^ Sutherland, James (1958) English Satire Archived 2022-12-04 at the Wayback Machine p. 1. There were a few exceptions, notably Byron, who integrated satire into some of his greatest works, yet shared much in common with his Romantic contemporaries. Bloom, p. 18.

- ^ Paul F. Grendler, Renaissance Society of America, Encyclopedia of the Renaissance, Scribner, 1999, p. 193

- ^ John Keats. By Sidney Colvin, p. 106. Elibron Classics

- ^ Thomas Chatterton, Grevel Lindop, 1972, Fyffield Books, p. 11

- ^ Weber, Patrick, Histoire de l'Architecture (2008), p. 63

- ^ a b Weber, Patrick, Histoire de l'Architecture (2008), pp. 64

- ^ a b Weber, Patrick, Histoire de l'Architecture (2008), pp. 64–65

- ^ Saule & Meyer 2014, p. 92.

- ^ Poisson & Poisson 2014.

- ^ Boyer 1961, 585.

- ^ Lefebvre, Henri (1995). Introduction to Modernity: Twelve Preludes September 1959 – May 1961. London: Verso. p. 304. ISBN 1-85984-056-6.

- ^ Ferchault 1957.

- ^ Christiansen, 176–78.

- ^ Rothstein, William; Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (2001). "Articles on Schenker and Schenkerian Theory in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd Edition". Journal of Music Theory. 45 (1): 204. doi:10.2307/3090656. ISSN 0022-2909. JSTOR 3090656.

- ^ Cunningham, A., and Jardine, N., ed. Romanticism and the Sciences, p. 15.

- ^ Bossi, M., and Poggi, S., ed. Romanticism in Science: Science in Europe, 1790–1840, p.xiv; Cunningham, A., and Jardine, N., ed. Romanticism and the Sciences, p. 2.

- ^ E. Sreedharan (2004). A Textbook of Historiography, 500 B.C. to A.D. 2000. Orient Blackswan. pp. 128–68. ISBN 978-81-250-2657-0.

- ^ in his published lectures On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and The Heroic in History of 1841

- ^ Ceri Crossley (2002). French Historians and Romanticism: Thierry, Guizot, the Saint-Simonians, Quinet, Michelet. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-97668-3.

- ^ Philip Clayton and Zachary Simpson, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Science (2006) p. 161

- ^ David Shenk (2007). The Immortal Game: A History of Chess. Knopf Doubleday. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-307-38766-0.

- ^ Swaner, Billy (2021-01-08). "Chess History Guide : Chess Style Evolution". Chess Game Strategies. Retrieved 2021-04-20.

- ^ Hartston, Bill (1996). Teach Yourself Chess. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-340-67039-2.

Sources[edit]

- Adler, Guido. 1911. Der Stil in der Musik. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel.

- Adler, Guido. 1919. Methode der Musikgeschichte. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel.

- Adler, Guido. 1930. Handbuch der Musikgeschichte, second, thoroughly revised and greatly expanded edition. 2 vols. Berlin-Wilmersdorf: H. Keller. Reprinted, Tutzing: Schneider, 1961.

- Barzun, Jacques. 2000. From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life, 1500 to the Present. ISBN 978-0-06-092883-4.

- Berlin, Isaiah. 1990. The Crooked Timber of Humanity: Chapters in the History of Ideas, ed. Henry Hardy. London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-4789-X.

- Bloom, Harold (ed.). 1986. George Gordon, Lord Byron. New York: Chelsea House Publishers.

- Blume, Friedrich. 1970. Classic and Romantic Music, translated by M. D. Herter Norton from two essays first published in Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Black, Joseph, Leonard Conolly, Kate Flint, Isobel Grundy, Don LePan, Roy Liuzza, Jerome J. McGann, Anne Lake Prescott, Barry V. Qualls, and Claire Waters. 2010. The Broadview Anthology of British Literature Volume 4: The Age of Romanticism Second Edition[permanent dead link]. Peterborough: Broadview Press. ISBN 978-1-55111-404-0.

- Bowra, C. Maurice. 1949. The Romantic Imagination (in series, "Galaxy Book[s]"). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Boyer, Jean-Paul. 1961. "Romantisme". Encyclopédie de la musique, edited by François Michel, with François Lesure and Vladimir Fédorov, 3:585–87. Paris: Fasquelle.

- Christiansen, Rupert. 1988. Romantic Affinities: Portraits From an Age, 1780–1830. London: Bodley Head. ISBN 0-370-31117-5. Paperback reprint, London: Cardinal, 1989 ISBN 0-7474-0404-6. Paperback reprint, London: Vintage, 1994. ISBN 0-09-936711-4. Paperback reprint, London: Pimlico, 2004. ISBN 1-84413-421-0.

- Cunningham, Andrew, and Nicholas Jardine (eds.) (1990). Romanticism and the Sciences. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-35602-4 (cloth); ISBN 0-521-35685-7 (pbk.); another excerpt-and-text-search source Archived 2022-12-04 at the Wayback Machine.

- Day, Aidan. Romanticism, 1996, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-08378-8, 978-0-415-08378-2.

- Eco, Umberto. 1994. "Interpreting Serials", in his The Limits of Interpretation Archived 2022-12-04 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 83–100. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-20869-6. excerpt Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Einstein, Alfred. 1947. Music in the Romantic Era. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Ferber, Michael. 2010. Romanticism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-956891-8.

- Friedlaender, Walter, David to Delacroix, (Originally published in German; reprinted 1980) 1952.[full citation needed]

- Greenblatt, Stephen, M. H. Abrams, Alfred David, James Simpson, George Logan, Lawrence Lipking, James Noggle, Jon Stallworthy, Jahan Ramazani, Jack Stillinger, and Deidre Shauna Lynch. 2006. Norton Anthology of English Literature, eighth edition, The Romantic Period – Volume D. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-393-92720-7.

- Grétry, André-Ernest-Modeste. 1789. Mémoires, ou Essai sur la musique. 3 vols. Paris: Chez l'auteur, de L'Imprimerie de la république, 1789. Second, enlarged edition, Paris: Imprimerie de la république, pluviôse, 1797. Republished, 3 vols., Paris: Verdiere, 1812; Brussels: Whalen, 1829. Facsimile of the 1797 edition, Da Capo Press Music Reprint Series. New York: Da Capo Press, 1971. Facsimile reprint in 1 volume of the 1829 Brussels edition, Bibliotheca musica Bononiensis, Sezione III no. 43. Bologna: Forni Editore, 1978.

- Grout, Donald Jay. 1960. A History of Western Music. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

- Hoffmann, Ernst Theodor Amadeus. 1810. "Recension: Sinfonie pour 2 Violons, 2 Violes, Violoncelle e Contre-Violon, 2 Flûtes, petite Flûte, 2 Hautbois, 2 Clarinettes, 2 Bassons, Contrabasson, 2 Cors, 2 Trompettes, Timbales et 3 Trompes, composée et dediée etc. par Louis van Beethoven. à Leipsic, chez Breitkopf et Härtel, Oeuvre 67. No. 5. des Sinfonies. (Pr. 4 Rthlr. 12 Gr.)". Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 12, no. 40 (4 July), cols. 630–42 [Der Beschluss folgt.]; 12, no. 41 (11 July), cols. 652–59.

- Honour, Hugh, Neo-classicism, 1968, Pelican.

- Hughes, Robert. Goya. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004. ISBN 0-394-58028-1.

- Joachimides, Christos M. and Rosenthal, Norman and Anfam, David and Adams, Brooks (1993) American Art in the 20th Century: Painting and Sculpture 1913–1993 Archived 2022-12-04 at the Wayback Machine.

- Macfarlane, Robert. 2007. 'Romantic' Originality Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine, in Original Copy: Plagiarism and Originality in Nineteenth-Century Literature Archived 2022-12-04 at the Wayback Machine, March 2007, pp. 18–50(33)

- (in Polish) Masłowski, Maciej, Piotr Michałowski, Warszawa, 1957, Arkady Publishers

- Noon, Patrick (ed), Crossing the Channel, British and French Painting in the Age of Romanticism, 2003, Tate Publishing/Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Novotny, Fritz, Painting and Sculpture in Europe, 1780–1880 (Pelican History of Art), Yale University Press, 2nd edn. 1971 ISBN 0-14-056120-X.

- Ruthven, Kenneth Knowles. 2001. Faking Literature. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-66015-7, 0-521-66965-0.

- Poisson, Georges; Poisson, Olivier (2014). Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (in French). Paris: Picard. ISBN 978-2-7084-0952-1.

- Samson, Jim. 2001. "Romanticism". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- Saule, Béatrix; Meyer, Daniel (2014). Versailles Visitor's Guide. Versailles: Éditions Art-Lys. ISBN 9782854951172.

- Smith, Logan Pearsall (1924) Four Words: Romantic, Originality, Creative, Genius. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Spearing, A. C. 1987. Introduction section to Chaucer's The Franklin's Prologue and Tale[full citation needed]

- Steiner, George. 1998. "Topologies of Culture", chapter 6 of After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation, third revised edition. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-288093-2.

- Wagner, Richard. Opera and Drama, translated by William Ashton Ellis. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995. Originally published as volume 2 of Richard Wagner's Prose Works (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., 1900), a translation from Gesammelte Schriften und Dichtungen (Leipzig, 1871–73, 1883).

- Warrack, John. 2002. "Romanticism". The Oxford Companion to Music, edited by Alison Latham. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866212-2.

- Waterhouse, Francis A. 1926. Romantic 'Originality' Archived 2016-05-06 at the Wayback Machine in The Sewanee Review, Vol. 34, No. 1 (January 1926), pp. 40–49.

- Weber, Patrick, Histoire de l'Architecture de l'Antiquité à Nos Jours, Librio, Paris, (2008) ISBN 978-229-0-158098.

- Wehnert, Martin. 1998. "Romantik und romantisch". Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart: allgemeine Enzyklopädie der Musik, begründet von Friedrich Blume, second revised edition. Sachteil 8: Quer–Swi, cols. 464–507. Basel, Kassel, London, Munich, and Prague: Bärenreiter; Stuttgart and Weimar: Metzler.

Further reading[edit]

This 'further reading' section may need cleanup. (February 2024) |

- Berlin, Isaiah. 1999. The Roots of Romanticism. London: Chatto and Windus. ISBN 0-691-08662-1.

- Blanning, Tim. The Romantic Revolution: A History (2011).

- Breckman, Warren, European Romanticism: A Brief History with Documents. New York: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2007. Breckman, Warren (2008). European Romanticism: A Brief History with Documents. Bedford/St. Martin's. ISBN 978-0-312-45023-6.

- Chaudon, Francis. 1980. The Concise Encyclopedia of Romanticism. Secaucus, N.J.: Chartwell Books. ISBN 0-89009-707-0.

- Clewis, Robert R., ed. The Sublime Reader. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019.

- Fay, Elizabeth. 2002. Romantic Medievalism. History and the Romantic Literary Ideal. Houndsmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Garofalo, Piero. 2005. "Italian Romanticisms." Companion to European Romanticism, ed. Michael Ferber. London: Blackwell Press, 238–255.

- Gaull, Marilyn. 1988. English Romanticism: The Human Context. New York and London: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-95547-7.

- Gay, Peter. 2015. Why the Romantics Matter. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300144291.

- Halmi, Nicholas. 2019. "European Romanticism." In The Cambridge History of Modern European Thought, ed. Warren Breckman and Peter Gordon, vol. 1, 40-64. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107097759.

- Halmi, Nicholas. 2021. "Romantic Thinking." In Thought: A Philosophical History, ed. Daniel Whistler and Panayiota Vassilopoulou, 61-74. ISBN 9780367000103.

- Hamilton, Paul, ed. The Oxford Handbook of European Romanticism (2016).

- Hesmyr, Atle. 2018. From Enlightenment to Romanticism in 18th Century Europe

- Honour, Hugh. 1979. Romanticism. New York: Harper and Row. ISBN 0-06-433336-1, 0-06-430089-7.

- McCalman, Iain (ed.). 2009. An Oxford Companion to the Romantic Age. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. Online at Oxford Reference Online (subscription required)

- Mazzeo, Tilar J. 2006. Plagiarism and Literary Property in the Romantic Period. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-812-20273-1

- O'Neill, J, ed. (2000). Romanticism & the school of nature : nineteenth-century drawings and paintings from the Karen B. Cohen collection. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Rosen, Charles. 1995. The Romantic Generation. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-77933-9.

External links[edit]

- Romantics & Victorians Archived 2016-07-01 at the Wayback Machine explored on the British Library Discovering Literature website

- The Romantic Poets

- The Great Romantics

- "Romanticism", Dictionary of the History of Ideas

- "Romanticism in Political Thought", Dictionary of the History of Ideas

- Romantic Circles—Electronic editions, histories, and scholarly articles related to the Romantic era

- Romantic Rebellion