Onondaga Lake

| Onondaga Lake | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Onondaga County, New York, United States |

| Coordinates | 43°05′21″N 76°12′37″W / 43.0891802°N 76.2103857°W[1] |

| Primary inflows | Ninemile Creek, Onondaga Creek |

| Primary outflows | Seneca River |

| Basin countries | United States |

| Max. length | 4.6 mi (7.4 km) |

| Max. width | 1 mi (1.6 km) |

| Surface area | 4.6 sq mi (12 km2) |

| Max. depth | 63 ft (19 m) |

| Surface elevation | 370 feet (110 m) |

Onondaga Lake is located in Central New York, immediately northwest of and adjacent to Syracuse, New York. The southeastern end of the lake and the southwestern shore abut industrial areas and expressways; the northeastern shore and northwestern end border a series of parks and museums.[2]

Although it is near the Finger Lakes region, it is not traditionally counted as one of the Finger Lakes. Onondaga Lake is a dimictic lake,[3] meaning that the lake water completely mixes from top to bottom twice a year. The lake is 4.6 miles (7.4 km) long and 1 mile (1.6 km) wide making a surface area of 4.6 square miles (12 km2).[3] The maximum depth of the lake is 63 feet (19 m) with an average depth of 35 feet (11 m).[4] Its drainage basin has a surface area of 642 square kilometers (248 sq mi), encompassing Syracuse, Onondaga County except the eastern and northern edges, the southeastern corner of Cayuga County and the Onondaga Nation Territory,[5] and supports approximately 450,000 people.[6]

Onondaga Lake has two natural tributaries that contribute approximately 70% of the total water flow to the lake. These tributaries are Ninemile Creek and Onondaga Creek. The Metropolitan Syracuse Wastewater Treatment Plant (METRO) contributes 20% of the annual flow.[4][7] No other lake in the United States receives as much of its inflow as treated wastewater.[6] The other tributaries, which include Ley Creek, Seneca River, Harbor Brook, Sawmill Creek, Tributary 5A, and East Flume, contribute the remaining 10% of water flow into the lake.[4][7] The tributaries flush the lake out about four times a year.[6] Onondaga Lake is flushed much more rapidly than most other lakes.[7] The lake flows to the northwest[8] and discharges into Seneca River which combines with the Oneida River to form the Oswego River, and ultimately ends up in Lake Ontario.[3]

The lake is sacred to the Onondaga Nation. The Onondaga people had control of the lake taken from them by New York State following the American Revolutionary War. During the late 19th century, European-Americans built many resorts along the lake's shoreline, as it was a destination of great beauty. The Onondaga Nation continues to have a religious and cultural presence on the shores of the lake, today.

With the industrialization of the region, much of the lake's shoreline was developed; domestic and industrial waste, due to industry and urbanization, led to the severe degradation of the lake. Unsafe levels of pollution led to the banning of ice harvesting as early as 1901. In 1940, swimming was banned, and in 1970 fishing was banned due to mercury contamination.[3][6] Mercury pollution is still a problem for the lake today.[4] Despite the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1973 and the closing of the major industrial polluter in 1986, Onondaga Lake remained one of the most polluted lakes in the United States until several initiatives, including a 15-year multi-stage program completed in late 2017, allowed the lake to reach criteria required by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and the United States Environmental Protection Agency.[9] This includes implementing a long-term operation, maintenance, and monitoring program to ensure the effectiveness of the remedy.[10]

The lake is included in an ongoing land rights action filed by the Onondaga Nation, which seeks the return of its ancestral homelands to promote environmental protection in conjunction with affirming Haudenosaunee sovereignty: “Onondaga Lake is the birthplace of Haudenosaunee democracy. Subsequently and consequently, the lake is the founding site of democracy for the U.S. people and, as such, should be protected as a national treasure instead of the chemical cesspool it has become.”[11]

History[edit]

Haudenosaunee history and land tenure[edit]

Onondaga Lake is the birthplace of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, a Confederacy of Indigenous Nations made up of the Mohawk, Onondaga, Oneida, Cayuga, and Seneca, and after 1772, the Tuscarora. The names of the Nations are directly connected to their ancestral homelands in current northwest New York State. Mohawk translates to people of the flint, Onondaga to people of the hills, Oneida to people of the standing stone, Cayuga to people of the marshy area, and Seneca to people of the great hills.[12] According to Grand River Mohawk scholar Susan M. Hill, “Among the Haudenosaunee, the names that the nations call themselves (and each other) denote key geographical features of their home territories… The recognition of geographic identity demonstrates the relationship to the land the people came from, the land they belonged to.”[12]

According to Joyce Tekahnawiiaks King, a Mohawk Turtle Clan member who served as a political administrator, Federal Justice of the Peace, director of the Haudenosaunee Environmental Task Force, and advisor to the New York State Department of Conservation Environmental Justice Committee throughout her career, the Haudenosaunee have responsibilities to the land and water they came from: “We speak in terms of responsibilities with respect to water, not in terms of water rights… From time immemorial, we have held the view that the ‘law of the land' is not man-made law, but a greater natural law, the Great Law of Peace. This law, in our view, is divine. The Haudenosaunee have a deep respect for the waters of the Earth.”[11] For the Haudenosaunee, law is made in cooperation with land and water.[13]

Onondaga Lake is central to The Great Law of Peace, or Kayaneren’kowa. According to Haudenosaunee histories, the five Nations had fallen away from the Original Instructions of Skyholder, or the Creator, who mandated that humans cultivate the land and live alongside “all things that grow" and game animals.[12] Included in the Original Instructions was the Thanksgiving Address, or Ohenton Kariwatehkwen.[11]

Water, including Onondaga Lake, is central to the Thanksgiving Address: “We give thanks to all the Waters of the world. We are grateful that the waters are still here and doing their duty of sustaining life on Mother Earth. Water is life, quenching our thirst and providing us with strength, making the plants grow and sustaining us all. Let us gather our minds together and with one mind, we send greetings and thanks to the Waters.”[14]

The Nations, who had “lost sight of the harmony and balance provided for in the Original Instructions”[12] split into warring factions. The Peacemaker brought the Nations together on the shores of Onondaga Lake, where he united them under the Great Law of Peace and formed the Haudenosaunee Confederacy[12][14]

The Haudenosaunee, or people of the longhouse, was founded as a conscious league based on principles of mutual respect and peaceful communication.[15][16] The Onondaga Nation website describes this event as the formation of “the first representative democracy in the West.”[17]

The event was recorded with the creation of the Hiawatha Belt, a wampum whose design would later be used as the Flag of the Iroquois Confederacy. This belt conveys the guiding principles of the Haudenosaunee, the story of the Great Peacemaker, and the founding of the league at Onondaga Lake.[18]

Onondaga Lake remains a sacred site for the Haudenosaunee, which King directly connects to Haudenosaunee environmental protection and sovereignty: “The value of water and the meaning of water law for the Native American called the Haudenosaunee cannot be separated from a yet-more foundational discussion on Haudenosaunee sovereignty and the right to protect land and Creation must be understood… Views on sovereignty are dependent upon the level of regard one has for the land itself (water, of course, included).”[11]

Early European settlement[edit]

Europeans began to learn about salt springs in the area in 1654, when the Onondagas revealed their presence to French explorers.[19] Jesuit missionaries visiting the Syracuse region in the same time period were the first to report on salty brine springs around the southern end of what they called "Salt Lake," known today as Onondaga Lake. The brine springs were reported to have extended around much of the lake for a distance of nearly 9 miles. They extended from the present-day towns of Salina through Geddes and from Liverpool to near the mouth of Ninemile Creek.[20] European settlers, mostly trappers and traders, followed the Jesuit missionaries and French explorers into the Syracuse area during the 17th and 18th centuries.[19] After the French and Indian War, British traders replaced the French, but encounters were limited.

British-American colonists began salt production in the area in the late 18th century. Following the victory of the United States in the American Revolutionary War, it made the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1788 with with supposed Haudenosaunee negotiators who were unauthorized by the Nations.[21]

Among its provisions was the transfer of the lands around the lake from the Onondaga Nation to local salt producers on the condition that the salt would be produced for the common use of everyone.[20] By 1822, due to a high incidence of malaria, the lake's water level was lowered after its outlet to the Seneca River was dredged. The low-lying swampy area, located in what is now the northern end of downtown Syracuse, was drained.[19]The completion of the Erie Canal through New York State in the mid-1820s and the commercial production of salt brought an increase in settlement of the area. The lake's western shore became increasingly industrialized as the nineteenth century progressed.[6][22]

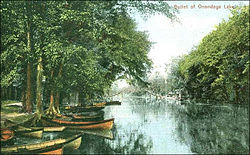

Onondaga Lake also became a popular resort area.[23] By the late 19th century, its shoreline was dotted with hotels, restaurants, and amusement parks.[19] The area was so popular that people traveled by railroad from as far as New York City to visit the lake. Fish from the lake were harvested and served in restaurants across the state.[24][6]

Industry[edit]

Salt brine and limestone were the key raw materials for the production of soda ash, used to make the industrial products of glass, chemicals, detergent, and paper. The abundance of salt brine and limestone in Onondaga Lake's watershed area attributed greatly for the industrialization along the lake's shoreline.[19] Beginning in 1838, New York State authorized the drilling of deep wells at several locations around the lake. The wells were intended to locate the source of the brine, but no source was located.

The Solvay Process Company, incorporated in 1881,[25] began drilling deep test holes in the area south of Syracuse in 1883. The company's main product was soda ash, integral to several industries. Eventually Solvay found halite deposits at a depth of 1,216 feet (371 m) below land surface in the southern end of Tully Valley. From 1890 to 1986, more than 120 wells were drilled into four halite beds on the east and west flanks of the valley.[20] Soda ash production began in 1884. The company was producing about 20 tons of soda ash per day, dumping most of its waste material directly into Onondaga Lake.[25] Eventually wastebeds were built along the southwest perimeter of the lake to contain the by-products of soda ash production.[8] In 1907, the New York State Attorney General threatened the Solvay Process Company with legal action over the direct discharge of Solvay waste material into the lake.[25]

As Syracuse's population began to grow in the 20th century, a surplus of pollution hit the lake hard. This lake was so close to the city that the effects of people's sewage, exhaust fumes, and dumping of unnecessary products all caused the lake to decline in popularity, fishing, and even swimming.[26]

In 1920, the Solvay Process Company merged with four other chemical companies, forming Allied Chemical and Dye Corporation. In 1950 it began the production of chlorine by mercury cell in 1950. Mercury-contaminated waste was also dumped directly into Onondaga Lake. Allied Chemical and Dye Corporation became Allied Chemical Corporation in 1958. Its continued practice of allowing mercury into the lake led to the federal and state governments banning fishing in 1970, due to mercury contamination of the fish. The US Attorney General sued Allied Chemical to halt the dumping of mercury into the lake. It is estimated that Allied Chemical was dumping approximately 25 pounds (11 kg) of mercury into Onondaga Lake per day. In 1981 Allied Chemical Corporation become Allied Corporation; in 1985 it changed its name to Allied-Signal, Inc. when it merged with the Signal companies. The company announced that it would close its operations in Syracuse because of changes in environmental laws, and in 1986 began dismantling its facility.[25]

In 1989, New York State filed a lawsuit against Allied-Signal, Inc. for its part in contamination of Onondaga Lake. New York State and Allied-Signal, Inc. signed an interim Consent Decree detailing the elements of a Remedial Investigation and Feasibility Study to be undertaken of the lake. In compliance with the Consent Decree, the study was conducted by Allied-Signal, Inc. which became Honeywell, Inc. in 1999.[25]

Non-salt-producing companies also became established along the Onondaga Creek valley from the mid-19th century to the early 20th century. Many of these companies drilled wells into the underlying sand to obtain water for cooling purposes. They were protecting dairy products and beer, storing perishable goods, and regulating temperature in office and storage buildings by such water use. Once used, the water was disposed of in nearby streams that drained to Onondaga Lake. This practice increased the salinity of the surface-water system.[20]

Parks and recreation[edit]

Long Branch Park[edit]

Long Branch Park is a public park in Onondaga County, New York, located in the town of Liverpool at 3813 Long Branch Road near NYS Route 370 and John Glenn Boulevard. The park is located on the northern shore of Onondaga Lake near Onondaga Lake Park, but it has no formal relation to it and is operate separately.

Onondaga Lake Park[edit]

Onondaga Lake Park is another county park. It hugs the eastern shore of the lake and has its offices at 6790 Onondaga Lake Trail in Liverpool. The park offers seven miles of shoreline, with a variety of areas for family picnics, including developed areas in Willow Bay and Cold Springs.[27]

Onondaga Lake Park Marina[edit]

The Onondaga Lake Park Marina is located on Onondaga Lake Parkway in Liverpool.[28]

Wegmans Good Dog Park[edit]

The Wegmans Good Dog Park was the first of its kind in Central New York and is located in the Cold Springs Mud Lock[29] section of Onondaga Lake Park. It is open from sunrise to sunset, seven days a week year round.[27]

Dogs are allowed to exercise without leashes in a 40,000 sq ft (3,700 m2) fenced-in area which includes an exercise area with tunnels, jumps and bridges complete with red fire hydrants.[27]

Entrance to the park is located at 49 Cold Springs Trail in Liverpooloff NYS Route 370. Suggested donation of $1 per person at the main gate. The park is maintained with private donations.[27]

Museums[edit]

This section needs to be updated. (April 2018) |

Mission of Sainte Marie[edit]

The Old French Fort at the Mission of Sainte Marie was the site of an early attempt by French Jesuits and colonists to establish a base in Central New York. In the 1930s, the remains of the original fort were replaced with what was claimed to be a "replica" or reconstruction of the site. Subsequent research has revealed that it was a poor imitation.[30]

In the 1980s, a decision was made to replace the structure with a historically accurate reconstruction. In addition, a visitor's center was built. This is used for the display of archeological artifacts recovered from the area, in a more accurate and "hands on" living museum.[30]

As of January 1, 2013, the Onondaga Historical Association (OHA) took over management of the Onondaga County facility known as "Sainte Marie among the Iroquois" located on the eastern shore of Onondaga Lake. The site is currently planning to repurpose the facility into a Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Heritage Center named Skä•noñh Center – Great Law of Peace Center. Skä•noñh, is an Onondaga welcoming greeting meaning Peace and Wellness.

Salt Museum[edit]

The Salt Museum was built around a still-standing boiling block chimney. It opened in 1933 during the Great Depression.[31]

Events[edit]

- Syracuse Hydrofest - The North American championship of hydroplane racing - annual event in the Willow Bay area of Onondaga Lake Park in mid-June.

- Lights on the Lake - Onondaga Lake Park in Liverpool from late November to early January.

Pollution[edit]

Sewage wastewater[edit]

One major source of pollution for Onondaga Lake is municipal sewage. For years, Syracuse dumped human waste into the lake with little or no treatment.[32][33] Before European settlement and the growth of a large population in the area, the lake was oligo-mesothropic, meaning that it contained low levels of aquatic plant blooms.[6]

The high levels of ammonia and phosphates due to the dumping of sewage wastewater have led to excessive algae growth in the lake.[33] When these excessive algae growths die, bacteria decompose the dead algae using large quantities of oxygen, which causes eutrophic and low-oxygen conditions.[34] The low oxygen levels lead to the choking out of fish and plants, especially in the deeper areas of the lake.[33] Eventually anoxic (oxygen-free) conditions set in parts of the lake and anaerobic decomposition takes place which emits harmful and foul-smelling gases like hydrogen sulfide.

Combined sewer overflow (CSO) also contributes pollution. In some areas of Syracuse, sewers carry both sanitary sewage and stormwater. During dry weather, these sewers carry all the sanitary sewage to Metro for treatment; however, during times of heavy rain or melting snow, the amount of water is greater than the capacity of the sewers. They overflow and discharge a combination of runoff and sanitary sewage into Onondaga Creek and Harbor Brook.[35] Through these tributaries, the CSO eventually reaches Onondaga Lake. CSO has been generating concerns about bacteria.[34] In the 1960s, Syracuse had ninety points where CSO could reach Onondaga Creek, Harbor Brook, or Ley Creek.[19]

Chemical pollution[edit]

The Allied Chemical Corporation contributed greatly to the chemical pollution of Onondaga Lake. The surface water was found to be contaminated with mercury whereas the sediments are contaminated with polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), pesticides, creosotes, heavy metals (lead, cobalt, and mercury), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), chlorinated benzenes, and BTEX compounds (benzene, ethylbenzene, toluene, xylene).[8][32][34][36] In Onondaga Lake the chlorinated benzenes are located in the southwest portion, in the form of a dense oily liquid that has settled into the sediments.[36] These chemicals were intentionally dumped into the lake or unintentionally seeped in from upland toxic waste sites or from the Solvay wastebeds located at the southwest end of Onondaga Lake. Approximately 6 million pounds (2.7 kt) of salty wastes made up of chloride, sodium, and calcium were dumped into the lake before Allied Chemical closed in 1986.[32]

Mercury contamination has been a major pollution issue. Between 1946 and 1970, 165,000 pounds (75,000 kg) of mercury was discharged into Onondaga Lake by Allied Chemical and Dye Corporation.[32] In 2002, the findings from the remedial investigation conducted by successor Honeywell, Inc., with the supervision of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC), reported that mercury contamination was found throughout the lake: the most elevated concentrations were in the sediments of the Ninemile Creek delta and of the southwestern portion of the lake.[37] A fishing ban was imposed in 1970 due to mercury contamination.[25]

In June of 2023, a scientific article was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association's (JAMA) Open Network Journal, which explored the association between arsenic levels and cardiovascular disease in children who lived near the lake. The article, "Exposure to Arsenic and Subclinical Cardiovascular Disease in 9- to 11-Year-Old Children, Syracuse, New York," explores the relationship between urinary arsenic, a heavy metal, and cardiovascular disease risk factors including blood vessel, and heart ventricle thickness. The study, done with 9-11 year old children, demonstrated a correlation between cardiovascular disease and high arsenic levels, as well as a correlation between high arsenic levels and children who lived in the southern and eastern areas near the bottom of Onondaga Lake.

Mudboils[edit]

Approximately 18 miles (29 km) south of Syracuse, the Tully Valley has unique hydro-geological features called mudboils. These mudboils are the cause of the excessive sedimentation of Onondaga Lake. The sediment enters Onondaga Creek, which flows north into the lake. Sediment loading is a problem because it degrades water quality, decreases water clarity, and reduces habitat for aquatic insects, fish spawning, and plants.[32][38]

Legal action and cleanup efforts[edit]

Sewage pollution cleanup[edit]

The first steps taken to control sewage pollution occurred in 1907 with the creation of the Syracuse Interceptor Sewage Board. It served to address sewage-related problems in Onondaga Creek and Harbor Brook. In 1960, Onondaga County established a sewer district and built the Metropolitan Sewage Treatment Plant ("Metro") on the south shore of the lake.[32]

In 1987, Atlantic States Legal Foundation (ASLF), a Syracuse-based organization providing legal and technical assistance to citizens and organizations dealing with environmental problems, filed a lawsuit against Onondaga County alleging that Metro and the combined sewer overflow (CSO) discharges were violating federal water pollution standards established under the Clean Water Act of 1972. The state of New York joined as a plaintiff with allegations that Onondaga County had also violated the New York State Environmental Conservation Law.[39] In 1988, ASLF, the state of New York, and Onondaga County reached a settlement outlined in a Consent Judgement which required the county to pay Upstate Freshwater Institute to create water quality models for the lake. These models would then form the basis for discharge limits imposed on the county's Metro facility. In 1990, the U.S. Congress created the Onondaga Lake Management Conference (Public Law 101-596, section 401). It ordered the group to develop a comprehensive revitalization, conservation, and management plan for Onondaga Lake that recommends priority corrective actions and compliance schedules for its cleanup. The Conference also called for coordination of implementing the plan. The largest responsibility of the Onondaga Lake Management Conference was the completion of the Onondaga Lake Management Plan.[40]

In 1997, New York State, Onondaga County, and ASLF reached an agreement, the Onondaga Lake Amended Consent Judgement (ACJ), on municipal wastewater collection and treatment improvements. The ACJ called for a schedule to attain compliance with the Clean Water Act.[41] The ACJ is a multi-year program designed to improve the water quality of Onondaga Lake while achieving full compliance with state and federal water quality regulations by December 1, 2002. ACJ projects are divided into three main categories: wastewater treatment, collection system, and lake and tributary monitoring.[40] In January 1998, a federal judge approved the ACJ [41] and in September 1999, the Onondaga Lake Management Conference approved and endorsed the Amended Consent Judgment (ACJ). It incorporated the ACJ into its 1993 Onondaga Lake Management Plan entitled, A Plan of Action.[40]

The final stage for ammonia discharge improvements occurred in 2004. The biological aerated filter (BAF) system allows for year-round nitrification of wastewater. In 2004, Metro's annual ammonia discharge was reduced to 152 metric tons and by 2005, the annual discharge fell to 21 metric tons. The ACJ also led to the creation of an ambient monitoring program (AMP) to track the effectiveness of the improvements made to the wastewater collection and treatment infrastructure. The AMP is designed to identify sources of materials to the lake, evaluate in-lake water quality conditions, and examine the interactions between Onondaga Lake and Seneca River.[42] Since 2007, Onondaga Lake has been in full compliance with the ambient water quality standards for ammonia. It was officially de-listed for that particular parameter in the State's 2008 list of impaired bodies of water.[43]

The ACJ achieved other successes. Between 1993 and 2006, the phosphorus discharges from Metro were decreased by 86%. Regarding contamination via CSOs, the ACJ required that by 2010 the county eliminate or capture for treatment 95% of the CSO volume generated during heavy rain and snow melt.[43]

Chemical pollution cleanup[edit]

In 1989, the State of New York filed a lawsuit against Allied-Signal, Inc. The lawsuit sought to compel the company to clean up the hazardous wastes that it and its predecessors had dumped into and around the lake.[41] In 2005, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) and the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued a Record of Decision that outlined the remediation plans of Onondaga Lake.[41] The Federal Court approved a Consent Decree in 2007, obliging Honeywell International, Inc. to implement the NYSDEC/EPA cleanup plan for the contaminated sediments in the bottom of the lake.[43] Honeywell signed the Consent Decree that same year and began the Remedial Design and Remedial Action for the Onondaga Lake Bottom Site.[41]

The cleanup plan called for the dredging of up to 2.65 million cubic yards of contaminated sediments to a depth that will allow for a cap to be built without losing any lake surface area. The plan also called for the installation of a barrier wall made of steel on the southwest corner of the lake to prevent contamination from the wastebeds from getting into the lake.[44] In 2011, Honeywell completed second-phase construction on this barrier wall.[41][45] The estimated cost of the cleanup plan was $451 million; an estimated $414 million in order to construct the remedy, followed by an annual maintenance cost of $3 million.[37]

Dredging began in July 2012. The sediments were hydraulically dredged from the bottom of the lake and piped to a sediment consolidation area in Camillus, New York. The dredging was completed in November 2014, a year ahead of schedule, having removed approximately 2.2 million cubic yards of contaminated sediment.[46]

The plan called for a cap covering 580 acres (230 ha) of lake-bottom. Capping began in August 2014, and was completed in 2016. Habitat restoration was completed in November 2017.[47]

In 2015, the EPA's first five-year review found that the addition of diluted calcium nitrate solution was effective in containing methylmercury (MeHg) in deep areas of the lake, which helped reduce MeHG concentrations throughout the lake and in zooplankton.[46] At depths of 10–19 meters (33–62 ft), the amount of MeHg has decreased by 97% since 2006.[48]

Audubon New York honored Honeywell with the 2015 Thomas W. Keesee Jr. Conservation Award for its role in “one of the most ambitious environmental reclamation projects in the United States.”[49]

As part of the scope of the cleanup project, Honeywell has funded and operates the Onondaga Lake Visitors Center, which opened in 2012.[50] The center, located on land owned by the New York State Department of Transportation adjacent to Honeywell's cleanup headquarters on the southwestern shore, presents information about the ongoing cleanup.[50]

The Onondaga Nation is not content with the Remedial Action plan for the Onondaga Lake Bottom Site. Their website states that the dredging plan will not include the additional 8 million cubic yards that the NYSDEC found to be contaminated. They do not believe that isolation caps are a permanent, reliable form of containment. The caps will not cover the entirety of the lake-bottom and they will eventually fail. The Onondaga Nation has said that New York State goals do not include making the lake swimmable or fishable, which are criteria included in the Clean Water Act. The total estimated plan, according to Onondaga Nation, of a thorough cleanup would cost $2.16 billion.[44]

In addition, the Onondaga Nation seeks biocultural restoration beyond improving water quality. According to Citizen Potawatomi plant biologist Robin Wall Kimmerer, who lives in the vicinity of Onondaga Lake in Syracuse,

In the Indigenous worldview, a healthy landscape is understood to be whole and generous enough to be able to sustain its partners. It engages land not as a machine but as a community of respected non-human persons to whom we humans have a responsibility. Restoration requires renewing the capacity not only for “ecosystem services” but for “cultural services” as well. Renewal of relationships includes water that you can swim in and not be afraid to touch. Restoring relationship means that when the eagles return, it will be safe for them to eat the fish. People want that for themselves, too. Biocultural restoration raises the bar for environmental quality of the reference ecosystem, so that as we care for the land, it can once again care for us.[14]

In 2022, the lake was declared to be at its cleanest in 100 years.[51]

Sedimentation control[edit]

Since 1992, the Onondaga Lake Partnership has supported the efforts of the United States Geological Survey (USGS) in the following remedial activities: the diversion of surface water away from the mudboils, the installation of a dam on the stream that flows from the mudboils area, and the drilling of wells to reduce the pressure around the mudboils (21).[35] The installation of several depressurization wells has led to dramatic decreases in sediment loading; an average of 30 tons per day was reduced to 1 ton per day.[43]

Fishing improvements[edit]

Dating back to the 1600s, Onondaga Lake has always shown reports of a cold-water system supporting certain types of fish. Around the late 1800s, degradation occurred and the fish that once thrived in the lake such as the American eel, Atlantic Salmon and Whitefish declined. The decrease in population resulted from the increase in temperatures because of severe pollution and human activities taking place. Even though the species are starting to gain numbers in this lake once again, the evidence shows that pollution had a direct impact on the fish that once inhabited this environment.[52]

A survey in 1928 showed the lake was habitat for only ten remaining species.[28] After clean-up and restoration efforts, researchers found a total of 54 species of fish captured in the lake between 1990 and 1999. The quality of sport fishing for large and small-mouth bass has gained national acclaim.[28]

In 2011, Brown Trout were listed among Onondaga Lake's Common Species, and Lake Sturgeon, stocked in nearby Oneida Lake, had returned.[53] In addition, in recent years,[when?] areas around the lake have become an overwintering spot for bald eagles, a demonstration that the fishing is good.

According to Kimmerer, these improvements are both the work of restoration efforts and the water itself:

Engineers, scientists, and activists have all applied the gift of human ingenuity on behalf of the water. The water, too, has done its part. With lessened inputs, the lakes and streams seem to be cleaning themselves as the water moves through. In some places, plants are starting to inhabit the bottom. Trout were found once again in the lake and when water quality took an upward turn it was front-page news. A pair of eagles have been spotted on the north shore. The waters have not forgotten their responsibility. The waters are reminding the people that they can use their healing gifts when we will use ours.[14]

In 1999, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) lifted the advisory on eating bass, white perch, and catfish from Onondaga Lake. The advisory against eating walleye remained in effect; and women of childbearing age, infants, and children under the age of 15 were advised against eating any of the fish from the lake.[41] In 2007, the NYSDOH updated its advisory, prohibiting the consumption of largemouth and smallmouth bass over 15-inches-long. No walleye, carp, channel catfish, and white perch of any size should be consumed. The Department of Health advises not more than four meals per month of brown bullhead and pumpkinseed, and not more than one meal per month of any species not listed.[54][55][56]

Onondaga sovereignty and environmental justice[edit]

The lake is also subject of a land right action filed on March 11, 2005, by the Onondaga Nation. The Onondaga Nation has been seeking the return of its land for over 200 years because its land was unlawfully ceded by “unauthorized Onondaga negotiators” in 1788.[21] The Onondaga did not want monetary reparations for the land, but the rights to the land. A newspaper article published in the New York Times on March 31, 2005, states, “What they want is influence in major policy discussions affecting the ecosystem in their ancestral lands. They also hope to use a favorable judgment to buy land to increase agricultural and housing opportunities, protect ancestors’ gravesites and safeguard the environment.”[57] The Onondaga Nation sought the protection and conservation of the natural resources within and affecting the Nation's land, and the security of Onondaga rights to hunt, fish, and gather resources for subsistence and cultural needs.[58] According to Sid Hill, the Tadodaho of the Haudenosaunee, the Onondaga people want the water, land, and air returned to its condition prior to being illegally taken by New York State in the 18th and 19th centuries.[59] Hill considers the degraded state of Onondaga Lake as evidence that neither New York State nor federal authorities can adequately care for the land and water resources.[60]

According to Kimmerer, “The Onondaga land rights action sought legal recognition of title to their home, not to remove their neighbors and not for development of casinos, which they view as destructive to community life. Their intention was to gain the legal standing necessary to move restoration of the land forward. Only with the title can they ensure that mines are reclaimed and that Onondaga Lake is cleaned up.”[14]

The land rights action was dismissed by a federal judge on September 22, 2010.[58] The judge claimed that the suit “came too late and would be disruptive to people settled on the land.”[21] The Onondaga Nation then took the suit to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in 2014, and the commission allowed the Nation to pursue two of its claims in May 2023.

The Onondaga Nation sees the environmental protection of Onondaga Lake as inextricably tied to fights for Haudenosaunee sovereignty and justice for nonhuman actors: “The Onondaga people still live by the precepts of the Great Law and still believe that, in return for the gifts of Mother Earth, human people have responsibility for caring for the nonhuman people, for stewardship of the land. Without title to their ancestral lands, however, their hands were tied to protect it.”[14]

According to Kimmerer and researchers at the Onondaga Environmental Institute, the Onondaga land rights action is both a fight for Haudenosaunee sovereignty and environmental justice. Tom Perreault, a geography professor at Syracuse University, collaborated with Sarah Wraight and Meredith Perreault at the Onondaga Environmental Institute, a non-profit focused on “environmental research, education, planning and restoration in Central New York”[61] on “Environmental Injustice in the Onondaga Lake Waterscape, New York State, USA,” in which they say, “Onondaga leaders argue that infringement of their nation’s traditional resource use rights and desecration of its aboriginal territory, especially places like Onondaga [L]ake that are central to its culture, have harmed their people’s cultural, economic, physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being.”[62] Further, Kimmerer quotes Clan Mother Audrey Shenandoah: “In this action, we seek justice. Justice for the waters. Justice for the four-leggeds and the wingeds, whose habitats have been taken. We seek justice, not just for ourselves, but justice for the whole of Creation.”[14]

Onondaga Nation is also seeking avenues for cooperation via the precepts of the Kaswentha, or Two-Row Wampum. The Kaswentha is a treaty belt that represents a 17th-century agreement between early Dutch settlers and the Haudenosaunee based on mutual respect. The wampum depicts two ships: one, a Dutch sailing ship, the other a Haudenosaunee birch bark canoe.[63][64]

Kimmerer argues that the precedent of the Kaswentha demonstrates the Onondaga Nation’s negotiating skills: “The Onondaga Nation, perhaps the oldest continuing democracy on the planet, protected much of its land and lifeways from the European settlers’ encroachment through skillful negotiations, beginning with the [Kaswentha] and continuing through subsequent treaties based on the same principles of sovereignty and mutual respect.[63]

Former chief of the Saint Regis Mohawk tribe and first director of the Haudenosaunee Environmental Task Force James Ransom and anthropologist Kreg Ettenger argue for a system of environmental cooperation based on the principles of the Kaswentha and Haudenosaunee teachings: “As in the past, when our two societies would come together to face a common enemy or scourge, the key to success in forming partnerships lies in focusing on the river that we travel, not on the vessels and their differences. With respect to contemporary environmental problems, the Kaswentha provides a useful and powerful image for partnerships based on protection of the natural world.”[64] This system of environmental cooperation would include valuing both indigenous knowledge and western knowledge systems to enter into collaborative partnerships. These partnerships would necessitate the recognition and protection of the “sovereignty and autonomy of each society (the ship and canoe) while allowing for the sharing of information and ideas and the creation of mutually acceptable solutions."[64]

Ultimately, the Onondaga Nation seeks to restore Onondaga Lake to a state that supports and honors both human and non-human life, even if full restoration may no longer be possible: “Restoration is imperative for healing the earth, but reciprocity is imperative for long-lasting, successful restoration. Like other mindful practices, ecological restoration can be viewed as an act of reciprocity in which humans exercise their caregiving responsibility for the ecosystems that sustain them.”[14]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Onondaga Lake". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved Jan 16, 2021.

- ^ New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (October 2008). "Citizen Participation Plan for the Onondaga Lake Bottom Subsite Remedial Design Program" (PDF). p. 15. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d Matthews, David A.; Steven W. Effler; Carol M. Matthews (Nov–Dec 2000). "Ammonia and Toxicity Criteria in Polluted Onondaga Lake, New York". Water Environment Research. 72 (6): 731–741. Bibcode:2000WaEnR..72..731M. doi:10.2175/106143000X138355. JSTOR 25045448. S2CID 94640834.

- ^ a b c d Driscoll, Charles T. "Background of Onondaga Lake". Mercury in Onondaga Lake. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ^ "Onondaga Lake Watershed". Onondaga Lake Partnership. Archived from the original on 2013-12-21. Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Onondaga Lake". The Upstate Freshwater Institute (UFI). Archived from the original on 27 December 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.()

- ^ a b c "Onondaga Lake". Onondaga Lake Partnership. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ^ a b c "Onondaga Lake" (PDF). US Environmental Protection Agency. 29 January 2013.

- ^ "Final Habitat Enhancements Mark Successful Completion of Honeywell's Onondaga Lake Cleanup".

- ^ "Sustainable Restoration Plan".

- ^ a b c d King, Joyce Tekahnawiiaks (2007). [Haudenosaunee.” Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy, vol. 16, no. 3, 2007, https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cjlpp/vol16/iss3/1. "The Value of Water and the Meaning of Water Law for the Native Americans Known as the Haudenosaunee"]. Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy. 16 (3): 449–472 – via Law Commons.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ a b c d e Hill, Susan M. (2017). The Clay We Are Made of: Haudenosaunee Land Tenure on the Grand River. University of Manitoba Press. pp. 16–43.

- ^ Keeler, Kyle (2024-03-01). "Toward a Literature of Landed Resistance: Land's Agency in American Literature, Law, and History". American Literature. 96 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1215/00029831-11092045. ISSN 0002-9831.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kimmerer, Robin Wall (2013). Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Milkweed Editions. pp. 310–40.

- ^ Lyons, Oren (1998). "The American Indian in the Past". Exiled in the land of the free: democracy, indian nations & the U.S. constitution. Santa Fe: Clear Light. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-940666-50-4.

- ^ Lyons, Scott Richard (2000). "Rhetorical Sovereignty: What Do American Indians Want from Writing?". College Composition and Communication. 51 (3): 447–468. doi:10.2307/358744. ISSN 0010-096X.

- ^ "Onondaga Lake". Onondaga Nation. 2014-02-18. Retrieved 2024-05-02.

- ^ "Hiawatha Belt". Onondaga Nation. 2014-06-18. Retrieved 2024-05-02.

- ^ a b c d e f "Human Use of Onondaga Lake". Onondaga Lake Partnership. Archived from the original on 2014-04-16. Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- ^ a b c d Kappel, William M. "Salt Production in Syracuse, New York ("The Salt City") and the Hydrogeology of the Onondaga Creek Valley" (PDF). Department of Interior U.S. Geological Survey.

- ^ a b c Hill, Michael (2023-09-30). "Rejected by US courts, Onondaga Nation take centuries-old land rights case to international panel". AP News. Retrieved 2024-05-02.

- ^ "Citizen Participation Plan for the Onondaga Lake Bottom Subsite Remedial Design Program" (PDF). New York State Department of Environmental Conservation.

- ^ "Onondaga Lake: We Stand at a Fork in the Road". Syracuse Peace Council. Archived from the original on 2012-03-17. Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- ^ "History of Onondaga Lake". Onondaga Community College, 2010. Archived from the original on June 12, 2010. Retrieved November 20, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f "Honeywell & Onondaga Lake: A Timeline". Onondaga Nation. Archived from the original on 2012-03-11.

- ^ New York. Department of Environmental Conservation .New York State DEC. New York, New York:, 2014. Print. <http://www.dec.ny.gov/chemical/8668.html>.

- ^ a b c d "Onondaga Lake Park". Onondaga County Parks, 2010. Archived from the original on November 27, 2010. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Onondaga Lake Park Longbranch Park". Syr-Area.com, 2010. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ "Directions". Onondaga County Parks, 2010. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ a b "Sainte Marie among the Iroquois". VirtualTourist, 2010. Archived from the original on May 4, 2010. Retrieved November 5, 2010.

- ^ Bell, Valerie Jackson (October 1998). "The Onondaga New York Salt Works (1654–1926)". Science Tribune. Retrieved November 5, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f "Water Quality in the Past". Onondaga Lake Partnership.

- ^ a b c "Onondaga Lake Contaminants of Concern". Onondaga Nation.

- ^ a b c "Region 2: Onondaga Lake". US Environmental Protection Agency. 29 January 2013.

- ^ a b "Pollutants & Onondaga Lake". Onondaga Lake Partnership.

- ^ a b "Onondaga Lake Contaminents of Concern". Onondaga Nation.

- ^ a b "Cleanup: Industrial Chemicals". Onondaga Lake Partnership.

- ^ Kappel, W. M.; Sherwood, D. A.; Johnston, W. H. (1996). Hydrogeology of the Tully Valley and characterization of mudboil activity, Onondaga County, New York (Report). U.S. Geological Survey. doi:10.3133/wri964043.

- ^ gcoin@syracuse.com, Glenn Coin | (2019-10-07). "30-year lawsuit that cleaned up Onondaga Lake is ending". syracuse. Retrieved 2024-05-02.

- ^ a b c "Legal Foundation for Onondaga Lake Cleanup". Onondaga Lake Partnership.

- ^ a b c d e f g "A Historical Perspective" (PDF). New York State Department of Environmental Conservation.

- ^ "Cleanup: Municipal Wastewater". Onondaga Lake Partnership.

- ^ a b c d "Onondaga Lake Superfund Site". US Department of Environmental Conservation.[dead link]

- ^ a b "The Onondaga Lake "Cleanup" Plan". Onondaga Nation.

- ^ O'Toole, Catie (7 December 2011). "Onondaga Lake cleanup hits milestone this week with completion of barrier wall". syracuse.com. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ a b "First Five-Year Review Report Onondaga Lake Bottom Subsite Of The Onondaga Lake Superfund Site Onondaga County, New York" (PDF). United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 17 April 2018.[dead link]

- ^ Coin, Glenn (17 November 2017). "Honeywell's Onondaga Lake habitat restoration: See before and after photos". syracuse.com. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ Coin, Glenn (9 October 2015). "EPA: Onondaga Lake is cleaner than expected after Honeywell dredging". syracuse.com. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ Coin, Glenn (6 November 2017). "Honeywell receives Audubon's highest award for Onondaga Lake cleanup". syracuse.com. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ a b Riede, Paul (November 15, 2012). "Onondaga Lake Visitor Center offers upbeat picture of massive cleanup". The Post-Standard. Syracuse, New York. Retrieved 2014-09-27.

- ^ Coin, Glenn (6 December 2022). "Onondaga Lake's remarkable transformation: Once a cesspool, now at its cleanest in 100 years". Syracuse Post-Standard. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ Tango, Peter, and Neil Ringler. The Role of Pollution and External Refugia in Structuring the Onondaga Lake Fish Community. 1. 12. Taylor & Francis Online, 2009. 81-90. Print.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-15. Retrieved 2012-11-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Fish". Onondaga Lake Partnership.

- ^ "State Health Department Issues Annual Fish Advisories". www.health.ny.gov. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ Watson, Taylor (26 February 2017). "Despite Onondaga Lake remedial efforts, some blame corporate influence for blocking lake's full restoration". The Daily Orange.

- ^ Semple, Kirk (2005-03-31). "Hoping to Reverse History and Pollution". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-05-02.

- ^ a b "Onondaga Land Rights Action Background". Neighbors of Onondaga Nation.

- ^ Kehow, Robert. "Neighbor to Neighbor, Nation to Nation: Water Connects Us All". Syracuse Peace Council.

- ^ "Onondaga Nation Announce Land Rights Action Promising No Evictions and No Casinos". Neighbors of Onondaga Nation.

- ^ "Mission". Onondaga Environmental Institute. Retrieved 2024-05-02.

- ^ Perreault, Tom; Wraight, Sarah; Perreault, Meredith (2012). "Environmental Injustice in the Onondaga Lake Waterscape, New

York State, USA". Water Alternatives. 5 (2): 485–506 – via Environment Complete.

{{cite journal}}: line feed character in|title=at position 61 (help) - ^ a b Kimmerer, Robin Wall (October 2015). "HONOR THE TREATIES PROTECT THE EARTH". Earth Island Journal. 30 (3): 22–25.

- ^ a b c Ransom, James W; Ettenger, Kreg T (2001-08). "'Polishing the Kaswentha': a Haudenosaunee view of environmental cooperation". Environmental Science & Policy. 4 (4–5): 219–228. doi:10.1016/s1462-9011(01)00027-2. ISSN 1462-9011.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)