Talk:TwixT

| This article is rated Start-class on Wikipedia's content assessment scale. It is of interest to the following WikiProjects: | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

How to improve Start Class assessment?[edit]

What can be done to improve this article? There are very few references about this game to cite, and those that have been published offer little in the way of useful additional information, although they might be more approachable for general readers. Should I publish a book on Twixt and then cite that? Most of the information provided is a result of personal experience.

Besides the citation issue, what actual information about Twixt is lacking here? One might even argue that the tutorial on how to play extends beyond the purview of an encyclopedia, although I'm grateful that it has been allowed to remain.

A detailed critique on the writing style exhibited on the article page, and how it might better conform to the standards expected of a Wikipedia article, would be welcome. Thanks for your time. --Twixter (talk) 17:25, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- I would suggest radically cutting down the page. The detailed discussion of specific strategems is really inappropriate for a Wikipedia article about a game, and I say this as a big Twixt fan. This article should be about a third of its current length, or less. — crism (talk) 03:55, 25 May 2010 (UTC)

- I disagree that strategy is inappropriate for wikipedia. There are plenty of high-quality pages which include strategy information (Chess#Strategy and tactics (FA), Go (game)#Tactics (FA), Stratego#Strategy (B)). --Quantum7 18:19, 9 January 2013 (UTC)

- The game play notation is never explained. I'm not sure that the game play should be in the article at all, but if it is included, it should be explained. From context, I'm guessing that the *-notation means to add a connection, and ** means to add two? Or something like that? 69.247.154.15 (talk) 06:18, 9 January 2013 (UTC)

- As a reader with no prior exposure to TwixT, I actually thought the article was pretty clear. I probably would have rated it a C class page. It meets the 'substantial' content criterion, and I don't see any major holes. It is weak on references regarding the rules and strategy, but is adequately referenced for the historical information. To bring it up to B standards would take a bit of work:

- Original research in Basic Patterns. Unfortunately, but the section is very helpful to a beginner TwixT player, so I would hate to see it cut entirely. Can we take you up on your offer to publish a book, Twixter?

- The Sample Game section doesn't really fit on the main TwixT article. There are some sample games on wikipedia for other games (eg List of chess games), but they seem to be either notable for the game itself or else used to illustrate specific strategies. Maybe if there were a TwixT Strategy article the sample game could be moved there, but as of now there's not enough content to justify two pages, IMO.

- As 69.247.154.15 suggests, the notation could be mentioned briefly. It was obvious to me, but I've read a lot of chess games.

- The 'Where to Play' section should be combined with External Links.

- Significantly more references regarding rules and strategy

- --Quantum7 18:31, 9 January 2013 (UTC)

variants[edit]

Rather than risk deletion from the main Twixt page, I place some info on variants here.

Twixt Variants[edit]

Perhaps the most popular variant is called Twixt PP where PP means paper and pencil. The rules are almost identical to standard Twixt. The only difference is with regard to link removal. When you play with paper and pencil, links are never removed (no erasure necessary,) but your own links are allowed to cross each other. This means, for example, that a winning path might loop across itself. Crossed links are not inherently connected to each other. In other words, the object is still to form a sequence of pegs of your color, each directly linked to the next, which connects your border rows.

In terms of game outcome, for the vast majority of games, this rules change makes no difference. On the Little Golem turn-based server, thousands of games have been played, all using the PP ruleset. Of those, only a handful, less than 0.1%, can be pointed to as reasonably clear examples of games that probably would have ended differently under standard rules. Most of those are games which would have been a draw under standard rules instead of a win for one side. But one game almost certainly would have been a win for one side instead of the other. Here is a contrived example on a smaller board:

Under PP rules, black to move has an easy win with F9, linking to both E11 and H8. But under standard rules, black would have to first remove the F8/G10 link in order to place F9/H8, and that would allow white to then play at E9, double linking to D11 and G8. White is also threatening to play either i9, which is a triple link, or H10, which is unstoppably connected to the bottom. There is no way for black to effectively block all these threats.

Some players might argue that PP rules are cleaner than standard rules. For one thing, the incidence of draws is reduced. But draws are already quite rare under standard rules, my personal preference. I believe the extra complications that result from link removal add depth and beauty to the game. In the Randolph series of puzzles, link removal is an essential part of several of those puzzles, and they would not be particularly interesting or challenging positions under PP rules.

Row handicapping is another variant which offers a way for players of different strengths to both enjoy a challenging game together. The simplest handicap is to eliminate the pie rule. Beyond that, one dimension of the grid is reduced. The weaker player moves first and also has less distance to cross. On a physical board, this might be implemented with two extra pieces of neutral color which look nothing like pegs but which fit in the holes. These are placed in the two new corners of the board, which are out of play, to indicate the new location of one of the weaker player's border rows. Six rows plus move might be a reasonable handicap between an experienced player and a beginner. The idea is to find a handicap where each player wins about half the time. Of course there is no pie rule for any handicap game.

On the main article page, someone modified the last sentence above to:

Of course there is no pie rule for any handicap game, silly.

I changed it back. For one thing, personal opinion is not appropriate. Also, I have seen intelligent people deliberately make a weak first move in a handicap game because they did not comprehend the implications of having no swap rule. Calling them silly does not help them learn. --Twixter (talk) 14:32, 9 August 2009 (UTC)

Different size grids from the standard 24x24 could be regarded as variants. The 12x12 board shown here leads to a very short game. It might be useful for development of computer programs which play the game, but between humans it is not very interesting. Even on the 24x24 grid, tactical considerations tend to predominate. The opening phase is over quickly, and the rest of the game is spent attempting to tactically justify the plan which you are now stuck with. By comparison, Hex, which has a very similar game object, may have more monotonous tactics, but strategical considerations are much more important. In this sense, Hex is more like Go than Twixt is, since a single move is generally less committal, and mistakes may not be punished as quickly. In my opinion, a larger grid for Twixt would result in greater balance between tactics and strategy. Since most commercial sets use boards which are made from four "quadrants" which either clip together or are hinged, a 36x36 grid could be cobbled together from three sets of the same size. In Europe, there briefly appeared a Twixt knock-off called "Imuri" which used a 30x30 grid. The board had no holes, and lines were drawn to indicate where the links could be placed. But the manufacturing quality was not so great; for example, link paths were drawn at each corner between adjacent border rows (A2 to C1 etc.) This edition was removed from shelves after Mr. Randolph threatened suit.--Twixter 17:45, 13 February 2007 (UTC)

I am indebted to Mark Thompson for the variant Diagonal Twixt. This has the same rules as standard Twixt, but the border lines no longer run parallel to the square grid of holes. Mark's idea was for border lines which run at a 45 degree angle to the grid. You can see an image of such a board at the link given. Scroll to the bottom of the page. My version has the border lines running parallel to link paths. These variants result in many different tactical patterns. They feel like completely new games in this respect.--Twixter 21:08, 13 February 2007 (UTC)

3M and other odd rule sets For the sake of historical completeness, I should mention that the very first publication of the game from the 3M company in 1962 differed from today's standard rules in two respects. There was no pie rule, which Mr. Randolph was later persuaded to add for Schmidt Spiele and other European companies, and there was no mention of link (or peg) removal in the first edition. There are actually three 3M editions with three different rule wordings with regard to link removal and rearrangement.

The second one says "A player can reuse pegs and links he has previously placed on the board, removing them carefully and only if they are inactive strategically." Apparently, whoever wrote this thought the only reason to remove a link would be if you are running out of them. But it is much more likely that you would need to remove a link from a strategically active area, in order to give yourself the elbow room necessary to avoid a draw and create an unbroken chain of linked pegs.

The third one says "Before placing a peg, a player may, if he desires, carefully remove any pegs and links he has previously placed on the board. However he should be certain not to remove any pegs and/or links which would give his opponent the advantage." I should add that these rules do not restrict link addition to the peg just placed. So, this is technically correct. IMO these three wordings are likely the result of miscommunication between Mr. Randolph and 3M.

When Avalon Hill published Twixt in the US, they got the wording correct for link removal and rearrangement, but they still left out the pie rule.

There was once a group of postal Twixt players (before email,) mainly in Europe I believe, who were not satisfied with the rules regarding link rearrangement. I was not one of those players, so this information is second hand. I welcome correction of any inaccuracy. As I understand it, they felt that allowing link placement between pegs of yours already on the board could lead to a form of abuse of the system. Under standard rules, a player can remove as many of their own links and then add as many of their own newly unblocked links as they want in a single move, even if there is no strategic reason to do so. Since they were playing by mail and had to write down their moves, perhaps they didn't want to deal with some unnecessarily lengthy move description. So under their rules, You may add links only to the peg you just placed on the board. So for example if you want to add a new link between pegs already on the board, you would have to remove one of those pegs from the board and then place it back into the same hole, instead of adding a new peg to the board.

In all my experience with playing and observing thousands of Twixt games, I have never seen the sort of "griefer behavior" these postal players were apparently concerned about. Both of the current real time Twixt servers do implement standard rules which allow players to remove links, but the vast majority are not aware that they can, and the vast majority of games do not require it. Of course the fact that players just click to move these days means that no grief would be inflicted on your opponent by removing and rearranging lots of links superfluously. You would just increase the risk of making a mistake and allowing your opponent to cut you off.

Here is an external link which explains why it is sometimes useful to be able to add a link or links between pegs of yours already on the board.

Post on Board Game Geek website Twixter (talk) 14:11, 15 June 2020 (UTC)

Pie rule[edit]

The text currently says

- This "one-move equalization" was added by Randolph after 3M published his game. It is present in the Schmidt Spiele edition and all later editions.

It is my understanding that Randolph had a pie rule from the beginning, but 3M omitted the rule. I have no cite. Randall Bart Talk 00:20, 8 May 2009 (UTC)

I used to think so as well, but Klaus Hussmanns told me that he and other players suggested the pie rule to Randolph after the 3M edition came out. --Twixter (talk) 19:10, 5 September 2009 (UTC)

Sample game[edit]

This has clearly been copy-pasted by someone from their personal website, and clearly doesn't belong here. I don't even edit wikipedia but even I can tell that having some random guy's e-mail address on a wikipedia page is totally inappropriate. I was tempted to delete the whole lot but I don't want to hurt anyone's feelings (or look like I'm vandalising). At most have a link in the external links section at the bottom. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 92.27.55.215 (talk) 15:36, 16 June 2012 (UTC)

Well no, this was never on my website, but you have a valid point. I appreciate you did not delete it. I reproduce the sample game here on the Talk page, where I originally put it. Someone else moved it to the Article page. I also return the images to a readable size, and I update my email. Twixter (talk) 20:35, 28 March 2014 (UTC)

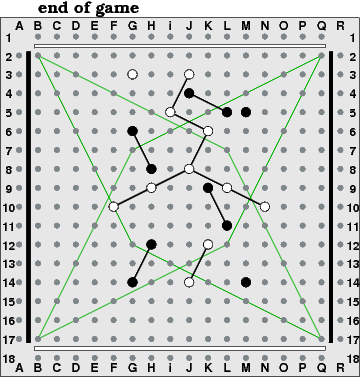

Here is an 18x18 game played on the K2z real time server. The actual moves of the game are in boldface, and variations are in plain text.

1.G3 Black has the option at this point to swap sides, but decides not to. 2.H8 This and the following two moves are straightforward attempts to block the opponent's previous peg. 3.L9 4.L11 Now white has no easy way to block L11. He must play the whole board, and try to find a move which makes as many threats as possible, or blocks as many of the opponent's threats as possible, depending on how you look at it. 5.F10

The point of F10 is that it makes two threats to reach the top, either straight up with something like D5, or through the center with J10*. The assumptions behind this plan are that F10 has a good chance of reaching the bottom border row, and L9 has a good chance of reaching the top. 6.G6*

Black tries to block both threats in one move. Now getting past G6 on the left looks very unlikely for white. At the same time, black threatens to cut straight across the top with L6, or through the center with i10*. 7.N10*

White played on the left side with F10, then black responded along the top with G6*, and now white plays on the right side with N10*. Such a clockwise (or counterclockwise) sequence of moves is called "windmilling" and seems to crop up often in the opening phase, especially on the standard 24x24 grid. Black might continue the windmill at this point with M13* or L15, but instead chooses to attack along the top. 8.M5

White now has a couple of tempting choices which lose. 9.M6 might be called a coign hammer attack, which sometimes works, but not here. 10.L7* 11.L8* 12.K9** and black wins.

Instead of 9.M6, a much more subtle losing move is 9.K7*.

White threatens M6* so black has to play 10.K4* and then white has the clever idea 11.F5*

E7* or H6* is white's double threat here. But black has a surprising resource: 12.F9*!

Now after 13.H6* 14.M13*

M13 cannot be prevented from reaching the right side, and on the left, black can use the threat of connecting to the H8 group. Here are three possible variations:

15.J10* 16.H13 17.H11** 18.F14* 19.Q13 20.P15 21.P16 22.O17* 23.Q14* 24.Q16* black wins,

or 15.D9* 16.G11* 17.G12* 18.E5* 19.i11* 20.i8 21.H9* 22.G9* 23.D4* 24.C4* 25.J8* 26.J6** 27.F7 trying to draw 28.J7 black must not remove his i8/J6 link yet 29.L5* now black can play at i5, remove the i8/J6 link, and add the chain of three links H8/J7/i5/K4. The notation for this is 30.i5-i8/J6+H8/J7/i5/K4 black wins.

Another variation is 15.i11 16.J12* 17.D9* 18.H13* 19.G12** 20.F14* 21.B14 22.D14 23.D15* 24.E16** 25.C12* 26.C17* black wins.

So 9.K7* Loses for white. But white did not play 9.K7*, he played 9.K6

What should the outcome of this position be? Let's do the battle on the bottom half first. If black can win across the bottom, there will be no need to bother with the top. What follows is a variation, though, not what black actually played.

10.K13* does not work because white has 11.O12*, for example 12.O16 13.L15

White connects to the bottom easily. Instead of 10.K13* black has 10.L15 11.J10* 12.G14 13.i14 14.J14* 15.E14 16.H13* 17.E12* 18.J9*!

J9 threatens i11** and at the same time supports black's attack across the top. Continuing this variation, 19.H11** 20.J4 21.J3 22.L5* 23.i5** 24.K7**

Black wins. It looks like 10.L15 would have won for black.

Returning to the game: 10.J4 11.J3 12.L5* 13.i5**

It's still not too late for black to win with 14.L15, but instead:

14.K9* This hands the win over to white.

15.J8** 16.M14 17.H9** 18.G14 19.J14 20.H12* 21.K12*

Black resigned.

Questions or comments about the variations seen here, can be directed to a help email, located at twixtfanatic@gmail.com

Online play external links[edit]

The external links section is a link farm. I've split out the online play links, including the "Where to play" links formerly embedded in the article. I think these are promotion, and should be removed. The AI links are also promotional. Some of the other external links are also superfluous to a scholarly presentation.Sbalfour (talk) 15:25, 14 January 2017 (UTC)

I've removed most of the external links - these should be to places where comprehensive or preferably scholarly information can be found; its not intended to be a link farm for online amusement. Wikipedia is not a gaming site.Sbalfour (talk) 14:46, 15 January 2017 (UTC)

lead needs reorged[edit]

The lead is supposed to be a summary of what's in the text, no new info presented here. But its bloated with mostly superfluous details that belong somewhere in the text. I think I'm going to be bold and fix it myself.Sbalfour (talk) 15:36, 14 January 2017 (UTC)

Basic patterns section[edit]

This section is a WP:GAMEGUIDE, totally unreferenced probably original research. I'm working on a related article Stratego, with the same issue and the analogous section there also has the same tag. "How-to" manuals tend to swamp the article, and such text can grow without bound for a deep strategy game. It may just be acceptable to remove the text to a website, and list an external link to that site. But the text cannot remain in the article without citation, and the citation should be to a published source by a credentialed player or a historic champion and represent game experience in sanctioned competition, akin to a book on master play or combinations in chess.Sbalfour (talk) 18:15, 14 January 2017 (UTC)

I should say, that a Strategy, Basic Patterns, or similar section is not necessary for GA or even FA (with rare exceptions - chess is one). Nor is it even a significant part of a concise scholarly article. The article is 'about the game', not about 'how to play the game'. A section that details things like, "how do I make a good opening", "how do I block my opponent", "what are some good plays", "what are some traps to avoid", etc belongs in a game manual, not in the encyclopedia. A reasonable (and short) description of gameplay may be a good addition to the article - things of interest to a general audience considering buying or playing the game. It answers questions like, is the game thoughtful (chess) or casual (yahtzee); how are the board and pieces used/deployed during the game; are there phases or characteristic maneuvers in the game (for example, the scrimmage lineup in football); is experience required to play a good game; is the skill similar to that in some other (perhaps more familiar game)? For an exemplary Strategy/Gameplay section, see Hex (board game)#Strategy or Chess#Strategy and tactics. Note how concise and narrative they are, as well as devoid of jargon and detail. Sbalfour (talk) 18:59, 28 January 2017 (UTC)

I've (re)moved the Basic Patterns section here, under the [Show] button to avoid clutter on the talk page. Do not replace it until it has been properly sourced.Sbalfour (talk) 19:12, 14 January 2017 (UTC)

Basic patterns

This section possibly contains original research. (June 2011) |

Despite such a large grid, games are frequently over before both sides have each made 25 moves. The tactics are very sharp and unforgiving. A knowledge of the most common peg patterns can help guide your eye towards the best move choices.

A setup is a pattern of two pegs of the same color which can connect to each other in a single move in two different ways. The gap between these pegs is generally difficult for the opponent to attack, since if one connection is blocked then the other is usually still available. There are five setups, each characterized by a name and by two numbers which represent the horizontal and vertical distances between these pegs. The larger value is listed first.

The yellow holes indicate where a third peg of the same color would form a double link connection. The red holes indicate possible points of attack for the opponent. For example, against white's beam setup in the top left, black could play at F7 which would link to H8. Placing a linked peg adjacent to a lone opposing peg this way is called a hammer attack. Black threatens to cut past E7 on one side or the other. In the top right, white could attack black's 3-3 tilt setup by linking to T8, threatening R9 or S10. Of course white would also be threatening in other directions, but our concern for the moment is just with setups and how to attack them. In the bottom right, black could launch a hammer attack with a link to S17, threatening Q16 or R15. Against the remaining two setups, the 2-0 mesh and the 1-1 short, a simple hammer attack will not work, because the two double linking paths are too widely separated. That does not mean that those setups are completely invulnerable, however.

There are plenty of other ways to place two pegs of the same color so that the gap between them is difficult to attack. The next diagram shows a few of them. The 5-2 gap is particularly strong. These two pegs can be connected in two moves in a variety of ways, usually too many for the opponent to block them all. The 5-0 gap is slightly more vulnerable. For example, if the O7 peg is unlinked, white might be able to attack at Q7. Then if black plays R6 threatening P5 or Q8, white could play O8, threatening N6 or R5.

The 3-0 gap involves some very tricky tactics. For example, if black tries to attack with an unlinked peg at O15, white could respond with N16 which threatens to double link at P15.

The 4-2 gap is technically not a setup, because there is only one way to connect these pegs in one move. But without a nearby peg, it may be difficult for black to attack this pattern anyway. If black plays L20, white could respond at K20 or at M20, forming a combination of a coign setup and a short setup. Since the short setup is so difficult to attack, white will probably manage to connect J21 to N19, albeit in three moves rather than one. White might also respond to L20 with either K21 or M19, which is much more complicated.

It is usually good enough to play close to the peg you want to connect to, since the most important thing is to block your opponent. You'll probably be able to complete the connection later in the game. For example, in the 4-3 gap, if white attacks with H14 black might respond with H15, which is a 2-2 gap from F17. This is four knight's moves away, but physically the pegs are close. If white continues the attack with G16 then black has H16 which threatens to double link at J15.

Here are a few more useful gaps to know. This is by no means an exhaustive list. The 6-1 gap can be vulnerable to attack like the 5-0 gap in the previous plate. With a white peg on H8 as shown, White could attack at H4, with the idea that black J4* would be answered by white F5*. In general, the "skinnier" the pattern of connecting holes is, such as with the 6-1 and 5-4 gaps, the more easily this gap could be attacked if the opponent has a peg close enough. But if there is no nearby opposing peg, such a pattern might be preferred because it crosses a large gap in few moves. An extreme example of this would be to extend a straight line of knight's moves by playing a 6-3 gap or 8-4 etc. If by making such a move you are also making another threat in another direction, this could be the most efficient possible use of the board. There are of course lots of gaps which would take three or more moves to connect. Shown here is the 7-3. Here black threatens to turn this into a "beam-tilt combination" by playing in either green hole (N15 or M18), or black might link to either blue hole (L16* or O17*) which would reduce this to a 5-2 gap.

The following diagrams use diagonal guide lines which emanate from the four corners of the common playing area. They are intended as a frame of reference on this huge grid of holes. They can help you see which side is going to win a corner battle.

The moves for each battle are numbered. One player makes the odd numbered moves, and the other player makes the even numbered moves. The notation shows an asterisk * for each link added to the peg that was just placed.

In the top left, black can hammer white with 1.G6*. If white responds with 2.D7* then after 3.E5* 4.C5* 5.C4* black has reached the crucial diagonal leading to B2. The top right shows the result of a similar fight with colors reversed, except here the hammer attack at T7 did not work because black was one row closer to the black border row, and black gained the crucial diagonal.

In a local battle, it is often a good idea to play where your opponent would like to play. In the bottom right, white has played 1.U21 which is a 2-1 block, or linking block, of the opponent and also forms a beam setup with U17. There are generally two ways to attack such a block, either a coign attack with 2.V21, or a short hammer attack with 2.T21. Neither attack works here. After 1.U21 2.V21 3.W20* 4.T22** 5.V22* white gains the corner. The bottom left is a mirror image, and shows the result after 1.D21 2.E21 3.F22* which threatens to cut through black's short setup with a double link at E20.

In the top left of this next diagram, white has another type of hammer attack. 1.G6 is called a mesh hammer. This works here because the white border row is so close that white can cut past black with either F4* or H4*, and also the 2-0 mesh setup between G6 and G8 is invulnerable to a simple hammer counterattack by black. The top right is a mirror image, and shows the result after 1.R6 2.Q6* 3.S4* 4.S7* 5.T7**.

The bottom left shows one way to defeat the mesh hammer attack. Black's "net" cannot be pierced by white in this instance. After 1.G20 2.H20** black threatens to cut through white's mesh setup with F19**. The bottom right is a mirror image which shows the point of black's defense.