Limit of a sequence

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2017) |

| 1 | 0.841471 |

| 2 | 0.958851 |

| ... | |

| 10 | 0.998334 |

| ... | |

| 100 | 0.999983 |

As the positive integer becomes larger and larger, the value becomes arbitrarily close to . We say that "the limit of the sequence equals ."

In mathematics, the limit of a sequence is the value that the terms of a sequence "tend to", and is often denoted using the symbol (e.g., ).[1] If such a limit exists, the sequence is called convergent.[2] A sequence that does not converge is said to be divergent.[3] The limit of a sequence is said to be the fundamental notion on which the whole of mathematical analysis ultimately rests.[1]

Limits can be defined in any metric or topological space, but are usually first encountered in the real numbers.

History[edit]

The Greek philosopher Zeno of Elea is famous for formulating paradoxes that involve limiting processes.

Leucippus, Democritus, Antiphon, Eudoxus, and Archimedes developed the method of exhaustion, which uses an infinite sequence of approximations to determine an area or a volume. Archimedes succeeded in summing what is now called a geometric series.

Grégoire de Saint-Vincent gave the first definition of limit (terminus) of a geometric series in his work Opus Geometricum (1647): "The terminus of a progression is the end of the series, which none progression can reach, even not if she is continued in infinity, but which she can approach nearer than a given segment."[4]

Pietro Mengoli anticipated the modern idea of limit of a sequence with his study of quasi-proportions in Geometriae speciosae elementa (1659). He used the term quasi-infinite for unbounded and quasi-null for vanishing.

Newton dealt with series in his works on Analysis with infinite series (written in 1669, circulated in manuscript, published in 1711), Method of fluxions and infinite series (written in 1671, published in English translation in 1736, Latin original published much later) and Tractatus de Quadratura Curvarum (written in 1693, published in 1704 as an Appendix to his Optiks). In the latter work, Newton considers the binomial expansion of , which he then linearizes by taking the limit as tends to .

In the 18th century, mathematicians such as Euler succeeded in summing some divergent series by stopping at the right moment; they did not much care whether a limit existed, as long as it could be calculated. At the end of the century, Lagrange in his Théorie des fonctions analytiques (1797) opined that the lack of rigour precluded further development in calculus. Gauss in his etude of hypergeometric series (1813) for the first time rigorously investigated the conditions under which a series converged to a limit.

The modern definition of a limit (for any there exists an index so that ...) was given by Bernard Bolzano (Der binomische Lehrsatz, Prague 1816, which was little noticed at the time), and by Karl Weierstrass in the 1870s.

Real numbers[edit]

In the real numbers, a number is the limit of the sequence , if the numbers in the sequence become closer and closer to , and not to any other number.

Examples[edit]

- If for constant , then .[proof 1][5]

- If , then .[proof 2][5]

- If when is even, and when is odd, then . (The fact that whenever is odd is irrelevant.)

- Given any real number, one may easily construct a sequence that converges to that number by taking decimal approximations. For example, the sequence converges to . The decimal representation is the limit of the previous sequence, defined by

- Finding the limit of a sequence is not always obvious. Two examples are (the limit of which is the number e) and the arithmetic–geometric mean. The squeeze theorem is often useful in the establishment of such limits.

Definition[edit]

We call the limit of the sequence , which is written

- , or

- ,

if the following condition holds:

- For each real number , there exists a natural number such that, for every natural number , we have .[6]

In other words, for every measure of closeness , the sequence's terms are eventually that close to the limit. The sequence is said to converge to or tend to the limit .

Symbolically, this is:

- .

If a sequence converges to some limit , then it is convergent and is the only limit; otherwise is divergent. A sequence that has zero as its limit is sometimes called a null sequence.

Illustration[edit]

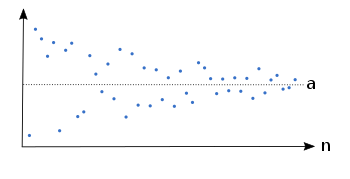

-

Example of a sequence which converges to the limit .

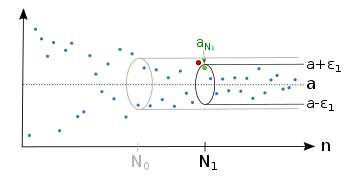

-

Regardless which we have, there is an index , so that the sequence lies afterwards completely in the epsilon tube .

-

There is also for a smaller an index , so that the sequence is afterwards inside the epsilon tube .

-

For each there are only finitely many sequence members outside the epsilon tube.

Properties[edit]

Some other important properties of limits of real sequences include the following:

- When it exists, the limit of a sequence is unique.[5]

- Limits of sequences behave well with respect to the usual arithmetic operations. If and exists, then

- For any continuous function , if exists, then exists too. In fact, any real-valued function is continuous if and only if it preserves the limits of sequences (though this is not necessarily true when using more general notions of continuity).

- If for all greater than some , then .

- (Squeeze theorem) If for all greater than some , and , then .

- (Monotone convergence theorem) If is bounded and monotonic for all greater than some , then it is convergent.

- A sequence is convergent if and only if every subsequence is convergent.

- If every subsequence of a sequence has its own subsequence which converges to the same point, then the original sequence converges to that point.

These properties are extensively used to prove limits, without the need to directly use the cumbersome formal definition. For example, once it is proven that , it becomes easy to show—using the properties above—that (assuming that ).

Infinite limits[edit]

A sequence is said to tend to infinity, written

- , or

- ,

if the following holds:

- For every real number , there is a natural number such that for every natural number , we have ; that is, the sequence terms are eventually larger than any fixed .

Symbolically, this is:

- .

Similarly, we say a sequence tends to minus infinity, written

- , or

- ,

if the following holds:

- For every real number , there is a natural number such that for every natural number , we have ; that is, the sequence terms are eventually smaller than any fixed .

Symbolically, this is:

- .

If a sequence tends to infinity or minus infinity, then it is divergent. However, a divergent sequence need not tend to plus or minus infinity, and the sequence provides one such example.

Metric spaces[edit]

Definition[edit]

A point of the metric space is the limit of the sequence if:

- For each real number , there is a natural number such that, for every natural number , we have .

Symbolically, this is:

- .

This coincides with the definition given for real numbers when and .

Properties[edit]

- When it exists, the limit of a sequence is unique, as distinct points are separated by some positive distance, so for less than half this distance, sequence terms cannot be within a distance of both points.

- For any continuous function f, if exists, then . In fact, a function f is continuous if and only if it preserves the limits of sequences.

Cauchy sequences[edit]

A Cauchy sequence is a sequence whose terms ultimately become arbitrarily close together, after sufficiently many initial terms have been discarded. The notion of a Cauchy sequence is important in the study of sequences in metric spaces, and, in particular, in real analysis. One particularly important result in real analysis is the Cauchy criterion for convergence of sequences: a sequence of real numbers is convergent if and only if it is a Cauchy sequence. This remains true in other complete metric spaces.

Topological spaces[edit]

Definition[edit]

A point of the topological space is a limit or limit point[7][8] of the sequence if:

- For every neighbourhood of , there exists some such that for every , we have .[9]

This coincides with the definition given for metric spaces, if is a metric space and is the topology generated by .

A limit of a sequence of points in a topological space is a special case of a limit of a function: the domain is in the space , with the induced topology of the affinely extended real number system, the range is , and the function argument tends to , which in this space is a limit point of .

Properties[edit]

In a Hausdorff space, limits of sequences are unique whenever they exist. This need not be the case in non-Hausdorff spaces; in particular, if two points and are topologically indistinguishable, then any sequence that converges to must converge to and vice versa.

Hyperreal numbers[edit]

The definition of the limit using the hyperreal numbers formalizes the intuition that for a "very large" value of the index, the corresponding term is "very close" to the limit. More precisely, a real sequence tends to L if for every infinite hypernatural , the term is infinitely close to (i.e., the difference is infinitesimal). Equivalently, L is the standard part of :

- .

Thus, the limit can be defined by the formula

- .

where the limit exists if and only if the righthand side is independent of the choice of an infinite .

Sequence of more than one index[edit]

Sometimes one may also consider a sequence with more than one index, for example, a double sequence . This sequence has a limit if it becomes closer and closer to when both n and m becomes very large.

Example[edit]

- If for constant , then .

- If , then .

- If , then the limit does not exist. Depending on the relative "growing speed" of and , this sequence can get closer to any value between and .

Definition[edit]

We call the double limit of the sequence , written

- , or

- ,

if the following condition holds:

- For each real number , there exists a natural number such that, for every pair of natural numbers , we have .[10]

In other words, for every measure of closeness , the sequence's terms are eventually that close to the limit. The sequence is said to converge to or tend to the limit .

Symbolically, this is:

- .

The double limit is different from taking limit in n first, and then in m. The latter is known as iterated limit. Given that both the double limit and the iterated limit exists, they have the same value. However, it is possible that one of them exist but the other does not.

Infinite limits[edit]

A sequence is said to tend to infinity, written

- , or

- ,

if the following holds:

- For every real number , there is a natural number such that for every pair of natural numbers , we have ; that is, the sequence terms are eventually larger than any fixed .

Symbolically, this is:

- .

Similarly, a sequence tends to minus infinity, written

- , or

- ,

if the following holds:

- For every real number , there is a natural number such that for every pair of natural numbers , we have ; that is, the sequence terms are eventually smaller than any fixed .

Symbolically, this is:

- .

If a sequence tends to infinity or minus infinity, then it is divergent. However, a divergent sequence need not tend to plus or minus infinity, and the sequence provides one such example.

Pointwise limits and uniform limits[edit]

For a double sequence , we may take limit in one of the indices, say, , to obtain a single sequence . In fact, there are two possible meanings when taking this limit. The first one is called pointwise limit, denoted

- , or

- ,

which means:

- For each real number and each fixed natural number , there exists a natural number such that, for every natural number , we have .[11]

Symbolically, this is:

- .

When such a limit exists, we say the sequence converges pointwise to .

The second one is called uniform limit, denoted

- ,

- ,

- , or

- ,

which means:

- For each real number , there exists a natural number such that, for every natural number and for every natural number , we have .[11]

Symbolically, this is:

- .

In this definition, the choice of is independent of . In other words, the choice of is uniformly applicable to all natural numbers . Hence, one can easily see that uniform convergence is a stronger property than pointwise convergence: the existence of uniform limit implies the existence and equality of pointwise limit:

- If uniformly, then pointwise.

When such a limit exists, we say the sequence converges uniformly to .

Iterated limit[edit]

For a double sequence , we may take limit in one of the indices, say, , to obtain a single sequence , and then take limit in the other index, namely , to get a number . Symbolically,

- .

This limit is known as iterated limit of the double sequence. The order of taking limits may affect the result, i.e.,

- in general.

A sufficient condition of equality is given by the Moore-Osgood theorem, which requires the limit to be uniform in .[10]

See also[edit]

- Limit point

- Subsequential limit

- Limit superior and limit inferior

- Limit of a function

- Limit of a sequence of functions

- Limit of a sequence of sets

- Limit of a net

- Pointwise convergence

- Uniform convergence

- Modes of convergence

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b Courant (1961), p. 29.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Convergent Sequence". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-08-18.

- ^ Courant (1961), p. 39.

- ^ Van Looy, H. (1984). A chronology and historical analysis of the mathematical manuscripts of Gregorius a Sancto Vincentio (1584–1667). Historia Mathematica, 11(1), 57-75.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Limits of Sequences | Brilliant Math & Science Wiki". brilliant.org. Retrieved 2020-08-18.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Limit". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-08-18.

- ^ Dugundji 1966, pp. 209–210.

- ^ Császár 1978, p. 61.

- ^ Zeidler, Eberhard (1995). Applied functional analysis : main principles and their applications (1 ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-387-94422-7.

- ^ a b Zakon, Elias (2011). "Chapter 4. Function Limits and Continuity". Mathematical Anaylysis, Volume I. p. 223. ISBN 9781617386473.

- ^ a b Habil, Eissa (2005). "Double Sequences and Double Series". Retrieved 2022-10-28.

Proofs[edit]

- ^ Proof: Choose . For every ,

- ^ Proof: choose (the floor function). For every , .

References[edit]

- Császár, Ákos (1978). General topology. Translated by Császár, Klára. Bristol England: Adam Hilger Ltd. ISBN 0-85274-275-4. OCLC 4146011.

- Dugundji, James (1966). Topology. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 978-0-697-06889-7. OCLC 395340485.

- Courant, Richard (1961). "Differential and Integral Calculus Volume I", Blackie & Son, Ltd., Glasgow.

- Frank Morley and James Harkness A treatise on the theory of functions (New York: Macmillan, 1893)