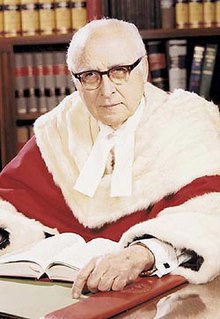

Emmett Matthew Hall

Emmett Matthew Hall | |

|---|---|

| |

| Puisne Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada | |

| In office January 10, 1963 [1] – March 1, 1973 | |

| Nominated by | John Diefenbaker |

| Preceded by | Charles Holland Locke |

| Succeeded by | Brian Dickson |

| Chief Justice of Saskatchewan | |

| In office 1961–1962 | |

| Nominated by | John Diefenbaker |

| Preceded by | William Melville Martin |

| Succeeded by | E. M. Culliton |

| Chief Justice of the Court of Queen's Bench for Saskatchewan | |

| In office 1957–1961 | |

| Nominated by | John Diefenbaker |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 29, 1898 Saint-Colomban, Quebec, Canada |

| Died | November 12, 1995 (aged 96) Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada |

| Political party | Progressive Conservative |

| Spouse |

Isabel Parker (m. 1922) |

| Children | John Hall; Marian Wedge |

| Alma mater | University of Saskatchewan |

| Profession | Lawyer |

Emmett Matthew Hall, CC (November 29, 1898 – November 12, 1995) was a Canadian lawyer, civil liberties advocate, Supreme Court of Canada judge and public policy advocate. He is considered one of the fathers of the Canadian system of Medicare, along with his fellow Saskatchewanian, Tommy Douglas.

Early life[edit]

Hall was born in Saint-Colomban, Quebec, the fourth of eleven children of James Hall and Alice Shea. His parents were descendants of generations of impoverished farmers of Irish descent in the Saint-Colomban area.[2][3][4] Seeking a better life, his family moved to Saskatoon, Saskatchewan in 1910, when Hall was age 12, to take over a dairy farm. The Halls were Roman Catholics, and Emmett served as an altar boy at Saint Paul's Cathedral in Saskatoon.[4]

Hall was in the audience on July 29, 1910, when Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier laid the cornerstone for the University of Saskatchewan.[3] Hall studied law at the College of Law at the University of Saskatchewan, putting himself through by teaching French in local schools.[2] One of his classmates was John Diefenbaker, future Prime Minister of Canada.[3] He received his law degree from the University of Saskatchewan in 1919.

Hall attempted to enlist in 1917, but was rejected as medically unfit, because he had been born blind in one eye.[5]

In 1922, Hall married Isabel Parker, a legal stenographer from Humboldt, Saskatchewan. They had two children, John Hall, who became a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, and Marian Wedge, who like her father, entered the legal profession and was appointed to the Saskatchewan Court of Queen's Bench.[4]

Legal career[edit]

Hall was called to the bar in 1922 and spent the next thirty-five years in private practice.[2][5] He became a leading litigator in the Saskatchewan bar, with a reputation for being hard-nosed.[3]

In 1928, at 29 years of age, Hall appeared in the Supreme Court of Canada as counsel for the appellants in Glenn and Babb v. Schofield.[6] His clients were farmers who were being sued by the owner of some free-range horses. The horses had eaten a large amount of grain which had spilled from the farmers' grain bins. One of the horses died from over-eating, and others were sickened. The Supreme Court ruled that Hall's clients had taken reasonable steps to store their grain from spillage and dismissed the action against them. The case was the first of Hall's six appearances in the Supreme Court. Hall was successful in five of those cases,[6][7][8][9][10] losing only one case.[11] In one of his successful cases, the Supreme Court paid him the ultimate accolade for an appellate lawyer: the Court did not find it necessary to call on him in oral argument and ruled in his favour based solely on Hall's written arguments.[7]

Hall acted as the defence counsel in the 1928 Maloney v. Dealtry libel trial. The plaintiff John James Maloney was a prominent member of the Ku Klux Klan who came to Saskatchewan to promote the Klan in preparation for the upcoming 1929 Saskatchewan general election which had shown signs of religious tension being a decisive factor, with the Klan raising anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic fervour. The plaintiff accused the defendant of seditious libel for comments made in a publication he printed and which, Hall argued as counsel, were seditious because they had caused a public fracas. Hall lost the case and the defendant was fined $200 and prohibited from publishing such material in the future. The Ku Klux Klan burnt an effigy of Hall in response to his participation in the case.[citation needed]

In 1935, Hall, along with a fellow Saskatoon lawyer, Paul G. Makaroff, defended the cases of many of the On-to-Ottawa trekkers against charges brought against them for their part in the Regina riot of July of that year. One police officer, Charles Miller was killed in the line of duty, and a trekker later died of injuries from the riot. Many believed that the trekkers were bolsheviks, but Hall and Makaroff believed that the riot had been provoked by the police. They were successful in having many of the charges quashed. Hall lost friends for his role in defending the trekkers.[4]

In 1935, Hall was appointed King’s Counsel. Later, he was elected a bencher of the Law Society of Saskatchewan, becoming President of the Law Society in 1952. He also taught law at the College of Law.[5]

Community involvement[edit]

Hall was active in the Saskatoon community, serving on both the Saskatoon Catholic Separate School Board and the Catholic Hospital Board. In the 1948 provincial general election, Hall stood for election for the Progressive Conservative Party, in the riding of Hanley. He was defeated, coming in third place, behind the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) and Liberal candidates.[12]

Judicial career[edit]

In 1957, Hall was appointed Chief Justice of the Court of Queen's Bench for Saskatchewan by his old law school classmate, John Diefenbaker, who had just won a minority government. He was elevated to the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal in 1961, when he was appointed Chief Justice of Saskatchewan. The next year, Diefenbaker appointed him to the Supreme Court of Canada. Hall served on the high court until his retirement in 1973.

One of Hall's most influential judgments was Calder v. British Columbia (Attorney General), dealing with aboriginal title.[13] Hall wrote compelling reasons arguing that aboriginal title existed in British Columbia under the common law. The Supreme Court divided on the issue, 3-3, so his opinion was not implemented. However, his judgment is credited with persuading Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau to open land-claim negotiations with First Nations. Hall's judgment also contributed to the entrenchment of aboriginal rights in the Constitution in 1982.[3]

In 1967, Hall was the sole dissent in the Supreme Court's reference decision upholding the 1959 conviction of Steven Truscott for capital murder. In his dissent, Hall argued that the trial had not been conducted according to law and that grave errors had been committed. He would have allowed the appeal and ordered a new trial.[14]

Public policy advocate[edit]

Royal Commission on Health Services[edit]

In 1961, while Chief Justice of the Queen's Bench, Hall was appointed by the Diefenbaker government to chair a royal commission on the national health system. The question of health care was a major issue at the time. In the 1960 Saskatchewan general election, the CCF government of Tommy Douglas had run on a platform of implementing a universal health care plan. The issue was extremely controversial. When the Saskatchewan government enacted the Saskatchewan Medical Care Insurance Bill in the fall of 1961, it triggered a strike by the doctors in Saskatchewan, which led to some changes to the provincial plan. The federal government's choice of Hall to lead the commission reassured the medical community, which had pressed for an inquiry to look at alternatives to the universal medicare system proposed by the Saskatchewan government.[4]

The Hall Commission heard from hundreds of witnesses. Hall closely questioned them, and was struck by the inequities in the Canadian health system and the lack of access to health care.[3] He continued to conduct the inquiry after his appointment to the Supreme Court of Canada. The Hall Commission issued its report in 1964. To the surprise of many, Hall recommended the nationwide adoption of Saskatchewan's model of public health insurance. In fact, his recommendations went further than the Saskatchewan plan, proposing additional publicly funded benefits, such as free dental coverage for schoolchildren and welfare recipients and free prescription glasses and drugs for the needy and elderly. "The only thing more expensive than good health care," he argued, "is no health care."[4]

By the time of his report, the Diefenbaker government had been replaced by the Liberal government of Lester B. Pearson. The Pearson government was deeply divided on the issue of health care,[15] and took some time to reach a decision. Eventually, the federal government implemented the medicare system which was at the core of Hall's recommendations, on a cost-share basis with the provinces. The new system came into force in July, 1968.[4]

Additional public inquiries[edit]

Hall chaired numerous other royal commissions and public inquiries.

While he was still on the Supreme Court, he conducted a public inquiry into education, at the request of the government of Ontario. Reporting in 1968, the Hall-Dennis Report recommended child-centred education and a flexible curriculum. The report also argued against the separation of handicapped children and slow learners from other students.[3] The report was blamed by opponents as contributing to a decline in educational standards.[4]

After he retired from the Supreme Court, Hall conducted an inquiry into the rail system in western Canada, with a particular focus on grain transportation. He also served as an arbitrator and mediator in strikes by national railway workers, grain handlers, and air traffic controllers.[3] Hall also made recommendations on reforms to court structures.[5]

In 1979, the federal government appointed Hall to conduct a follow-up inquiry into the current state of the Canadian health care system. His report, issued a year later, raised concerns about the growth of extra-billing and user fees. His report eventually led to the introduction of the Canada Health Act, which prohibited those practices.[15]

University chancellor[edit]

Hall served as the chancellor of two different universities: the University of Guelph, from 1971 to 1977, and the University of Saskatchewan, from 1979 to 1986. By a quirk of fate, he followed two former leaders of the federal Progressive Conservative party in the two positions. His predecessor as chancellor of Guelph was George Drew, who led the party from 1948 to 1956. At Saskatchewan, he succeeded his old law school chum, John Diefenbaker, who died in 1979.

Legacy[edit]

Historian J. L. Granatstein has described Hall as the most important Canadian judge of the 20th century.[3]

Hall had been indelibly marked by his experience going through the Great Depression in Saskatchewan. One of his friends and fellow Saskatchewanian, Ramon Hnatyshyn, former Governor General of Canada, commented: "They were tough times. You had a chance to see real deprivation and the importance of helping your fellow citizen."[4]

One of Hall's biographers, Dennis Gruending, characterised him as an "Establishment radical."[16] Gruending wrote that Hall was a study in contradictions. A member of the Establishment, he was more interested in justice than in privilege. Despite reaching the elite heights of his profession, he never forgot his own humble origins or the needs of the ordinary people that he encountered during his long life.[3] That was also reflected in his work on the Supreme Court, where he defended civil liberties and protected minority rights. Hall believed that Canadian society ought to embrace ethnic diversity, alleviate poverty, and redress the shameful treatment of Aboriginal peoples.[5]

On his retirement from the Supreme Court in 1974, Hall was made a Companion of the Order of Canada, "for a lifetime of service to the law and for his contributions to the improvement of health services and education."

At the age of 81, as he was wrapping up his second inquiry into health care, he was asked by a reporter when he would stop his activities. "When they bury me," Hall replied.[4] He remained active well into his 90s. During the federal election of 1993, he strongly criticised Preston Manning, the leader of the Reform Party of Canada, for proposing user fees for health care and the complete withdrawal of the federal government from the medicare system.[4]

Hall suffered a stroke in late 1993, shortly after celebrating his 95th birthday at a public dinner in his honour.[3] The stroke confined him to a wheelchair.[4]

Hall died on November 12, 1995, just short of his 97th birthday.

References[edit]

- ^ Frederick Vaughan, Aggressive in Pursuit: The Life of Justice Emmett Hall (University of Toronto Press, 2004) p163; Vaughn's appointment had been announced on November 23, 1962

- ^ a b c "Supreme Court of Canada Biography". Archived from the original on 2014-08-06. Retrieved 2014-08-04.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan: Hall, Emmett (1898–1996)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Emmett Hall (Obituary)", Macleans, November 27, 1995; published on-line by the Canadian Encyclopedia.

- ^ a b c d e The Honourable Emmett M. Hall Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, Saskatchewan Law Courts biography.

- ^ a b Glenn and Babb v. Schofield, [1928] SCR 208.

- ^ a b Coca-Cola Company of Canada Ltd. v. Forbes, [1942] S.C.R. 366.

- ^ Studer v. Cowper, [1951] S.C.R. 450.

- ^ Canada Egg Products Ltd. v. Canadian Doughnut Co. Ltd., [1955] S.C.R. 398.

- ^ Rural Municipality of Monet v Campbell, [1956] S.C.R. 763.

- ^ L.V. Wolfe and Sons v. Giesbrecht, [1945] S.C.R. 441.

- ^ Saskatchewan.Chief Electoral Officer, Provincial Elections in Saskatchewan 1905-1986, "General Election — June 24, 1948", p. 76.

- ^ Calder v. British Columbia (Attorney General), [1973] S.C.R. 313.

- ^ Reference Re: Steven Murray Truscott, [1967] SCR 309

- ^ a b "Emmett Hall Biography," The Justice Emmett Hall Memorial Foundation

- ^ Dennis Gruending, Emmett Hall: Establishment Radical (Toronto: Fitzhenry and Whiteside, 2005).

Further reading[edit]

- Dennis Gruending, Emmett Hall: Establishment Radical (Toronto: Fitzhenry and Whiteside, 2005).

- Vaughan, Frederick; Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History (2004). Aggressive in Pursuit: The Life of Justice Emmett Hall. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-3957-X.

External links[edit]

- 1898 births

- 1995 deaths

- Lawyers in Saskatchewan

- Canadian King's Counsel

- Canadian university and college chancellors

- Chancellors of the University of Saskatchewan

- Chancellors of the University of Guelph

- Companions of the Order of Canada

- Justices of the Supreme Court of Canada

- University of Saskatchewan alumni

- University of Saskatchewan College of Law alumni

- Canadian people of Irish descent

- People from Laurentides