Mesa of Lost Women

| Mesa of Lost Women | |

|---|---|

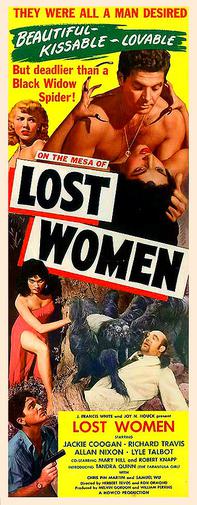

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Herbert Tevos Ron Ormond |

| Written by | Herbert Tevos |

| Produced by | G. William Perkins Melvin Gordon |

| Starring | Jackie Coogan Richard Travis Allan Nixon Lyle Talbot Mary Hill Robert Knapp Tandra Quinn (the Tarantula Girl) Chris Pin Martin Samuel Wu |

| Narrated by | Lyle Talbot |

| Cinematography | Karl Struss, A.S.C. Gil Warrenton, A.S.C. |

| Edited by | Hugh Winn, A.C.E. Ray H. Lockert W. Donn Hayes, A.C.E. |

| Music by | Hoyt S. Curtin |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Howco Productions, Inc. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 70 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Mesa of Lost Women is a 1953 American low-budget black-and-white science fiction film directed by Herbert Tevos and Ron Ormond[1] from a screenplay by Tevos and Orville H. Hampton, who is given on-screen credit only for dialogue supervision.

Plot[edit]

This article may require copy editing for failure to write in own words (versus massive cut-and-paste, cited but inappropriate), grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (October 2023) |

Grant Phillips and Doreen Culbertson get lost in the "Muerto Desert." They are nearly dead from dehydration and sunburn when discovered by Frank, an American oil surveyor, and his Mexican companion, Pepe. The two victims recover in the "Amer-Exico Field Hospital" somewhere in Mexico. Grant starts narrating his story to "Doc" Tucker, foreman Dan Mulcahey, and Pepe.

The film flashes back a year earlier in Zarpa Mesa. Famous scientist Leland Masterson arrives, having accepted an invitation from a fellow scientist, Dr. Aranya. Aranya has reportedly penned "brilliant" scientific treatises, and Masterson looks forward to meeting him. Aranya's theories intrigue Masterson, but Aranya states his work is not theoretical. He has already completed successful experiments creating both human-sized tarantula spiders and human women with the abilities and instincts of spiders. His creation, Tarantella, has regenerative abilities sufficient to regrow severed limbs. He expects her to have a lifespan of several centuries.[2] His experiments have had less success in male humans, who become afflicted with disfiguring dwarfism.[2]

A horrified Masterson denounces Aranya and his creations. In response, Aranya, with the help of his henchman, injects him with a drug, turning him into a doddering simpleton. Masterson is later found wandering in the desert. Declared insane, he is placed in the "Muerto State Asylum," a psychiatric hospital. Masterson eventually escapes. Two days later, he is seen in an unnamed American town on the U.S.-Mexico border. Also present are Tarantella, businessman Jan van Croft, and his fiancée, Doreen. They were heading to Mexico for their wedding day, but their private airplane had engine problems and stranded them there. Jan's servant Wu is working with Tarantella.

Masterson's nurse at the asylum, George, tracks him to the bar. The entire bar, its patrons and the bartender observe Tarantella perform a dance. Masterson recognizes Tarantella, pulls a handgun, and shoots her. He then takes Jan, Doreen, and George hostage. He heads for Jan's private airplane and forces pilot Grant to prepare for takeoff despite the latter's protests that only one engine is fully functional. The aircraft departs with Doreen, George, Grant, Jan, Masterson, and Wu aboard. Meanwhile, Tarantella regenerates following her apparent death and leaves the bar.

Grant discovers that someone sabotaged the gyrocompass, resulting in their flying in the wrong direction. Unbeknownst to him, the saboteur is Wu. The airplane crash-lands atop Zarpa Mesa, where Aranya's creations were expecting them. The group dwindles with the deaths of George, Wu, and lastly, Jan.

The last three members of the group are then captured. Grant recognizes their captor's name is identical to the Spanish term for spider, "araña." Aranya cures Masterson of drug-induced imbecility, hoping to recruit him. This backfires as Masterson performs a suicide attack. He allows Doreen and Grant to escape, then causes an explosion that kills them all.

The flashback ends. At the hospital, Grant fails to convince anyone but Pepe of the truth in his story. Yet it is later revealed that at least one of Aranya's spider-women has survived.

Cast[edit]

Opening credits[edit]

- Jackie Coogan

- Allan Nixon

- Richard Travis

- Narrated by Lyle Talbot

- Mary Hill

- Robert Knapp

- Tandra Quinn

- Chris Pin Martin

- Harmon Stevens

- Nico Lek

- Kelly Drake

- John Martin

- George Burrows

- Candy Collins

- Delores Fuller

- Dean Reisner

- Doris Lee Price

- Mona McKinnon

- Sherry Moreland

- Ginger Sherry

- Chris Randall

- Dianne Fortier

- Karna Greene

- June Benbow

- Katina Vea

- Fred Kelsey

End credits[edit]

- Jackie Coogan as Doctor Aranya

- Richard Travis as Dan Mulcahey

- Allan Nixon as "Doc" Tucker

- Mary Hill as Doreen

- Robert Knapp as Grant Phillips

- Chris Pin Martin as Pepe

- Harmon Stevens as Masterson

- Nico Lek as Van Croft

- Samuel Wu as Wu

- John Martin as Frank

- Tandra Quinn as Tarantella

| John George | Aranya's dwarf servant |

| Angelo Rossitto | dwarf assistant in Aranya's laboratory |

| Julian Rivero | patron in cantina where Tarantella performs her dance |

| Suzanne Ridgeway | girl in cantina where Tarantella performs her dance |

| Margia Dean | Brunette girl in Aranya's laboratory |

Production[edit]

The film was originally made by Pergor Productions under the title Tarantula and was viewed and granted a Motion Picture Production Code seal in October 1951. The original director, Herbert Tevos (born Herbert Schoellenbach),[3] reportedly claimed to have had a film career in his native Germany and to have directed films starring Marlene Dietrich and Erich von Stroheim. Tevos also claimed to have directed the Dietrich film The Blue Angel (1930), which was actually directed by Josef von Sternberg. Mesa of Lost Women was Tevos/Schoellenbach's only known film credit.[4] When the producers had difficulty securing a distributor for the Tevos footage, it was sold to Howco Productions Inc. in the spring of 1952, with Ron Ormond assigned to direct additional material.[5] Tandra Quinn recalled that among the new sequences created by Ormond were the scenes of the Jackie Coogan and Quinn characters being killed.[6] Katherine Victor said that she was hired by Ormond in order to create her desert sequences.[7] Filming locations included the Red Rock Canyon State Park.[8]

The film's musical score was composed by Hoyt Curtin. It makes use of flamenco guitar and piano, combined in an apparent free jazz style. This music was later reused in the Ed Wood film Jail Bait (1954).[2][9] The narrator Lyle Talbot also appeared in several films by Wood, including Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959), as did the "spider-woman" actresses Dolores Fuller and Mona McKinnon.[2] The film also features the debut of Katina Vea as the spider-woman who first drove Masterson to the desert, who was later a regular in Jerry Warren films using the stage name Katherine Victor.[10] One of the dwarfs in the film was Angelo Rossitto, a veteran of Poverty Row horror films whose film career had started in the 1920s.[11]

Although Tarantella is a key character of the film, it was a silent part. Actress Quinn also had a silent part in The Neanderthal Man (1953), playing a deaf-mute. Decades later, Quinn recalled that she never received "a decent speaking part" in a film.[4] She reportedly chose her stage name by modifying one suggested by Tevos. He had suggested the stage name Tandra Nova. She agreed to the first name "Tandra", but thought the last name unsuitable and reminiscent of Lou Nova. She instead chose the last name "Quinn" in honor of dancer Joan Quinn.[4]

Mesa of Lost Women was noted for being one of several 1950s science fiction films that utilized wire-controlled giant spider props, the others being Cat-Women of the Moon (1953), Tarantula (1955), World Without End (1956), Queen of Outer Space (1958), and the Cat-Women of the Moon remake Missile to the Moon (1958).[12] The spider prop used in Mesa of Lost Women was limited in movement, a single jump being its only action feat.[12]

Release[edit]

The film was distributed in the United States by Howco Productions Inc. and reissued in 1956 through Ron Ormond Enterprises.

Critical reception[edit]

The movie has been criticized for its low-quality production and acting, most notably that of Harmon Stevens and Jackie Coogan. The loud and repetitive musical score by Hoyt S. Curtin, melding flamenco guitar and piano, is described variously as maddening and "very able, a sustained inspiration"[13]

Film critic Glenn Erickson wrote that "watching [the film] is like being on drugs. The storyline, the performances and simple narrative logic just don't add up. The direction is incompetent in a decidedly Ed Wood style: The camera is never in a good position and every insert and cutaway is awkward," adding that the "ridiculously complicated plot hides the fact that nothing really happens," and that the "film [has] lapses in judgment that boggle the mind."[14] In his review of the film for AllMovie, Richard Gilliam wrote that "[t]he story is more incoherent than non-linear, the characters are woodenly constructed, and the overall film is a dull, tepid mess."[15] Critic Nigel Honeybone described the film as "hopelessly muddled and misguided," claimed "the soundtrack will drive you insane as the same refrain is repeated again and again and again," and speculated that the film is "so bad you have to ask yourself, is it actually evil?"[16]

The film was also spoofed by RiffTrax.[17]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ MUBI

- ^ a b c d Dennis Grisbeck (July 2006). "Mesa of Lost Women (1953)". The Monster Shack. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ Warren, Bill Keep Watching the Skies!: American Science Fiction Movies of the Fifties, The 21st Century Edition McFarland, 12 Jan. 2017

- ^ a b c Weaver (2009), p. 212-231

- ^ "Mesa of Lost Women (1953) - Notes - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies.

- ^ p.221-225 Weaver, Tom Tandra Quinn Interview from I Talked with a Zombie: Interviews with 23 Veterans of Horror and Sci-fi Films and Television McFarland, January 1, 2009

- ^ p.386 Weaver, Tom Katherine Victor Interview Return of the B Science Fiction and Horror Heroes: The Mutant Melding of Two Volumes of Classic Interviews McFarland, 2000

- ^ Johnson (1996), p. 357

- ^ Craig (2009), p. 69-82

- ^ Weaver (2000), p. 385-386

- ^ Johnson (1996), p. 261

- ^ a b Johnson (1996), p. 23

- ^ Ron Ormond & Herbert Tevos

- ^ Erickson, Glenn. "Femme Fatale Collection: Mesa of Lost Women, Devil Girl From Mars, The Astounding She-Monster". DVD Talk. DVDTalk.com. Retrieved March 18, 2024.

- ^ Gilliam, Richard. "Mesa of Lost Women (1953)". AllMovie. Netaktion LLC. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- ^ Honeybone, Nigel (May 24, 2014). "Film Review: Mesa Of Lost Women (1953)". HorrorNews.Net. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- ^ RiffTrax

Sources[edit]

- Craig, Rob (2009), "Jail Bait (1954)", Ed Wood, Mad Genius: A Critical Study of the Films, McFarland & Company, ISBN 978-0-7864-5423-5

- Johnson, John (1996), "Wire Propelled Props", Cheap Tricks and Class Acts: Special Effects, Makeup, and Stunts from the Films of the Fantastic Fifties, McFarland & Company, ISBN 978-0-7864-0093-5

- Johnson, John (1996), "Giants and Midgets", Cheap Tricks and Class Acts: Special Effects, Makeup, and Stunts from the Films of the Fantastic Fifties, McFarland & Company, ISBN 978-0-7864-0093-5

- Johnson, John (1996), "Low Budget Filming and Convenient Sites", Cheap Tricks and Class Acts: Special Effects, Makeup, and Stunts from the Films of the Fantastic Fifties, McFarland & Company, ISBN 978-0-7864-0093-5

- Weaver, Tom (2000), "Katherine Victor", Return of the B Science Fiction and Horror Heroes: The Mutant Melding of Two Volumes of Classic Interviews Volume 21 of McFarland Classics Series, McFarland & Company, ISBN 978-0-7864-0755-2

- Weaver, Tom (2009), "Tandra Quinn", I Talked with a Zombie: Interviews with 23 Veterans of Horror and Sci-fi Films and Television, McFarland & Company, ISBN 978-0-7864-5268-2

External links[edit]

- Mesa of Lost Women at IMDb

- Mesa of Lost Women is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive

- 1953 films

- 1953 horror films

- 1950s science fiction films

- American black-and-white films

- American exploitation films

- Films about spiders

- Films directed by Ron Ormond

- Films set in Mexico

- Films set in the United States

- Giant monster films

- Mad scientist films

- 1950s science fiction horror films

- Films scored by Hoyt Curtin

- American science fiction horror films

- Films shot in California

- 1950s monster movies

- American monster movies

- 1953 directorial debut films

- 1950s English-language films

- 1950s American films