History of Kiribati

The islands which now form the Republic of Kiribati have been inhabited for at least seven hundred years, and possibly much longer. The initial Austronesian peoples’ population, which remains the overwhelming majority today, was visited by Polynesian and Melanesian invaders before the first European sailors visited the islands in the 17th century. For much of the subsequent period, the main island chain, the Gilbert Islands, was ruled as part of the British Empire. The country gained its independence in 1979 and has since been known as Kiribati.

Pre-history[edit]

For several millennia, the islands were inhabited by Austronesian peoples who had arrived from the Solomon Islands or Vanuatu. The I-Kiribati or Gilbertese people settled what would become known as the Gilbert Islands (named for British captain Thomas Gilbert by von Krusenstern in 1820) some time in between 3000 BC[1][2] and 1300 AD.[3] Subsequent invasions by Samoans and Tongans introduced Polynesian elements to the existing Micronesian culture, and invasions by Fijians introduced Melanesian elements. Extensive intermarriage produced a population reasonably homogeneous in appearance, language and traditions.

Contact with other cultures[edit]

In 1606 Pedro Fernandes de Queirós sighted Butaritari and Makin, which he named the Buen Viaje ('good trip' in Spanish) Islands.[4]

Captain John Byron passed through the islands in 1764 during his circumnavigation of the globe as captain of HMS Dolphin.[5]

In 1788, Captain Thomas Gilbert in Charlotte and Captain John Marshall in Scarborough. Messrs. Gilbert and Marshall passed close to Abemama, Kuria, Aranuka, Tarawa, Abaiang, Butaritari, and Makin without attempting to land on shore.[6]

Further exploration[edit]

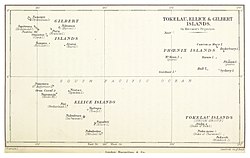

In 1820, the islands were named the îles Gilbert (in French, Gilbert Islands) by Adam Johann von Krusenstern, a Russian admiral of the Czar after the British Captain Thomas Gilbert, who crossed the archipelago in 1788. In 1824, French captain Louis-Isidore Duperrey was the first to map the whole Gilbert Islands archipelago. He commanded La Coquille on its circumnavigation of the earth (1822–1825).[7]

Two ships of the United States Exploring Expedition, USS Peacock (1828) and USS Flying Fish (1838), under the command of Captain Hudson, surveyed the Gilbert Islands of Tabiteuea, Nonouti, Aranuka, Maiana, Abemama, Kuria, Tarawa, Marakei, Butaritari, and Makin[8] (then called the Kingsmill Islands or Kingsmill Group in English). While in the Gilberts, they devoted considerable time to mapping and charting reefs and anchorages.[9] Alfred Thomas Agate made drawings of men of Butaritari and Makin.[10]

At one time, a subset of the northern Gilbert islands was known as Scarborough Islands and a subset of the southern Gilberts as the Kingsmill Group; in some 19th century texts, this last name of Kingsmills was applied to the entire Gilberts group.[11]

Missionaries[edit]

Missionaries began to be active in the Gilbert Islands in the 1850s. Dr Hiram Bingham II of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) arrived on Abaiang in 1857. The Roman Catholic faith was introduced on Nonouti around 1880 by 2 Gilbert islanders, Betero and Tiroi, who had become christians in Tahiti. Father Joseph Leray, Father Edward Bontemps and Brother Conrad Weber, Roman Catholic Missionaries of the Sacred Heart arrived on Nonouti in 1888.[12] The protestant missionaries of the London Missionary Society (LMS) were also active in the southern Gilberts. On 15 October 1870, Rev. Samuel James Whitmee of the LMS arrived at Arorae, and later that month he visited Tamana, Onotoa and Beru.[13] In August 1872, George Pratt of the LMS visited the islands.[14]

Visit of Robert Louis Stevenson to Abemama and Butaritari in 1889[edit]

Robert Louis Stevenson, Fanny Vandegrift Stevenson, and her son Lloyd Osbourne, stayed for 2 months on Abemama in 1889, which was described by Stevenson in his account of the 1889 voyage of the Equator published as In the South Seas[15][16] At the time of their visit, the High Chief was Tembinok', the last of the dozens of expansionist chiefs of Gilbert Islands of this period, despite Abemama historically conforming to the traditional southern islands' governance of their respective unimwaane. Tembinok' was immortalised in Stevenson's book as the "the last tyrant",[17] with Stevenson delved into the high chief's character and method of rule during his stay stay on Abemama; Tembinok' controlled the access of european traders to the atolls under his control and jealously guarded his revenue and his prerogatives as monarch.[16]

Robert Louis Stevenson, Fanny Vandegrift Stevenson and Lloyd Osbourne also visited Butaritari from 14 July 1889 to early August.[18] At this time Nakaeia was the ruler of Butaritari and Makin atolls, his father being Tebureimoa and his grandfather being Tetimararoa. Nakaeia was described by Stevenson as “a fellow of huge physical strength, masterful, violent … Alone in his islands it was he who dealt and profited; he was the planter and the merchant” with Stevenson describing his subjects toiling in servitude and fear.[16]

Nakaeia allowed two San Francisco trading firms to operate, Messrs. Crawford and Messrs. Wightman Brothers, with up to 12 Europeans resident on islands of the atolls. The presence of the Europeans, and the alcohol they traded to the islanders, resulted in periodic alcoholic binges that only ended with Nakaeia making tapu (forbidding) the sale of alcohol. During the 15 or so days that Stevenson spent on Butaritari the islanders were engaged in a drunken spree that threatened the safety of Stevenson and his family. Stevenson adopted the strategy of describing himself as the son of Queen Victoria so as to ensure that he would be treated as a person who should not be threatened or harmed.[16]

Robert Louis Stevenson, Fanny Vandegrift Stevenson and Lloyd Osbourne returned to Abemama in July 1890 during their cruise on the trading steamer, Janet Nicoll.[19]

Early traders and trading companies[edit]

The first traders resident in the Gilberts were Richard Randell and George Durant who arrived in 1846.[20] Durant moved on to Makin, while Randell remained on Butaritari.[21] The earliest trading companies on Butaritari were the Hamburg-based Handels-und Plantagen-Gesellschaft der Südsee-Inseln zu Hamburg (DHPG) with Pacific headquarters in Samoa, and On Chong (Chinese traders with Australian connections via the goldfields). The Japanese trading company Nanyo Boeki Kabushiki Kaisha established operations on Butaritari. Two San Francisco trading firms, Messrs. Crawford and Messrs. Wightman Brothers, were operating on Butaritari in 1889.[22]

W. R. Carpenter & Co. (Solomon Islands) Ltd was established in 1922.[23][24][25] Through the 1920s On Chong experienced gradual decline in its operations as the result of low copra prices. Eventually On Chong was taken over by W. R. Carpenter & Co. These traders helped Butaritari became the commercial and trading capital of the Gilbert Islands until Burns Philp, the trading company based in Sydney, Australia, moved to Tarawa, following the seat of political power.

Colonial era[edit]

Whalers, blackbirders, and merchant vessels arrived in great numbers in the 19th century, and the resulting upheaval fomented local tribal conflicts and introduced damaging European diseases. In an effort to restore a measure of order, the Gilbert Islands were declared as the British Protectorate by Captain Edward Davis of HMS Royalist (1883) on 27 May 1892.[26][27] The neighboring Ellice Islands (now Tuvalu) were declared a British Protectorate later in 1892.[28] The Gilbert and Ellice Islands Protectorate was administered as part of the British Western Pacific Territories (BWPT).[28]

British Western Pacific Territories[edit]

The BWPT were administered by a High Commissioner resident in Fiji until 1952, then in Honiara.

A Resident Commissioner, Charles Swayne, was appointed in 1893 following the protectorate on the Gilbert group and on the Ellice group becoming formal and effective in 1892. The protectorate's headquarters was established on Tarawa in 1896, where Resident Commissioner William Telfer Campbell presided from 1896 until 1908. The headquarters were then moved to Ocean Island (now Banaba), and continued upon the transition to a Crown Colony. This move in headquarters arose from the operations of the Pacific Phosphate Company resulting in good shipping connections to Ocean Island, and in any case the role of the British colonial authorities emphasised the procurement of labour for the mining and shipping of phosphate and keeping order among the workers.[29][30]

Ocean Island (now Banaba) was included in the protectorate in 1900 and then in the colony in 1916.[29][30] In the same year, Fanning Island and Washington Island were included in it together with the islands of the Union Islands (now Tokelau).[31]

In 1916, the administration of the BWTP changed as the islands became a Crown Colony on 12 January 1916. But the new colony remained under the jurisdiction of BWTP until 1971.[32]

Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony[edit]

The islands became a Crown Colony on 12 January 1916 by the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Order in Council, 1915.[33] Christmas Island was included in the colony in 1919 although it was contested by the U.S. under the Guano Islands Act of 1856.[34] The Union Islands were unofficially transferred to New Zealand administration in 1926 and officially in 1948. The Phoenix Islands were added in 1937 and the five islands of the Central and Southern Line Islands were added in 1972.[31]

The Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony continued to be administered by a Resident Commissioner. One very famous colonial officer in the colony was Sir Arthur Grimble (1888–1956), at first as a cadet officer in 1914, under Edward Carlyon Eliot who was Resident Commissioner of the BWPT then the colony from 1913 to 1920. This period is described in Eliot's book "Broken Atoms" (autobiographical reminiscences) (Pub. G. Bles, London, 1938) and in Sir Arthur Grimble's "A Pattern of Islands" (Pub. John Murray, London, 1952). Arthur Grimble became the Resident Commissioner of the colony in 1926. In 1930 Grimble, issued revised laws, Regulations for the good Order and Cleanliness of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands, which replaced laws created during the BWPT.

Ocean Island remained the headquarters of the colony until the British evacuation in 1942 because of the Japanese occupation of the Gilbert Islands. After World War II, the colony headquarters was re-established on Tarawa, first on Betio islet (then occupied by American forces following the Battle for Tarawa) and subsequently on Bairiki.[31][35][36]

World War II[edit]

Japan seized part of the islands during World War II to form part of their island defenses. On 20 November 1943, Allied forces threw themselves against Japanese positions at Tarawa and Makin in the Gilberts, resulting in some of the bloodiest fighting of the Pacific campaign. The Battle of Tarawa and the Battle of Makin (in fact Butaritari) were a major turning point in the war for the Allies, which battles were the implementation of "Operation Galvanic".[37]

Self-determination[edit]

Transition to self-determination[edit]

The formation of the United Nations Organisation after World War II resulted in the United Nations Special Committee on Decolonization committing to a process of decolonisation; as a consequence the British colonies in the Pacific started on a path to self-determination.

As a consequence of the 1974 Ellice Islands self-determination referendum,[38] separation occurred in two stages. The Tuvaluan Order 1975 made by the Privy Council, which took effect on 1 October 1975, recognised Tuvalu as a separate British dependency with its own government. The second stage occurred on 1 January 1976 when separate administrations were created out of the civil service of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony.[39]

Independence for Kiribati[edit]

The Gilberts obtained internal self-government in 1977 and held general elections in February 1978 which saw Ieremia Tabai elected Chief Minister at only age 27. Kiribati attained independence as a republic within the Commonwealth of Nations on 12 July 1979 by the Kiribati Independence Order 1979 made by the Privy Council of the United Kingdom.

Although the indigenous Gilbertese language name for the Gilbert Islands proper is Tungaru, the new state chose the name "Kiribati," the Gilbertese rendition of "Gilberts," as an equivalent of the former colony to acknowledge the inclusion of islands which were never considered part of the Gilberts chain.[40] The United States gave up its claims to 14 islands of the Line and Phoenix chains (previously asserted under the Guano Islands Act) in the 1979 Treaty of Tarawa.[41]

Independence[edit]

Following independence, the Kiribati head of state was Ieremia Tabai. At 29-years-old, Tabai served three terms as Beretitenti (President), from 1979 to 1991. Tabai was the youngest head of state in the Commonwealth of Nations.

In 1994, Teburoro Tito was elected Beretitenti. He was reelected in 1998 and 2002 but was ousted in a no-confidence vote in March 2003, and having served the maximum three terms, he is barred by the constitution from running for another term. Tito's temporary replacement was Tion Otang, the Council of State chairman. In 2003, a new presidential election was held, in which two brothers, Anote and Harry Tong, were the two main candidates (a third candidate, Banuera Berina, won just 9.1% of the vote.

Anote Tong, a London School of Economics graduate, won on 4 July 2003, and was sworn in as President soon afterward. He was re-elected in 2007 and in 2012 for a third term. [42]

In March 2016, Taneti Maamau was elected as the new President of Kiribati. He was the fifth president since the country became independent in 1979.[43] In June 2020, President Maamau won re-election for second four-year term. President Maamau was considered pro-China and he supported closer ties with Beijing.[44]

The Banaba issue[edit]

An emotional issue has been the protracted bid by the residents of Banaba to secede and have their island placed under the protection of Fiji. Because Banaba was devastated by phosphate mining,[29][30] the vast majority of Banabans was deported to the island of Rabi in the Fiji Islands in the 1940s where they now number some 5,000 and enjoy full Fijian citizenship. The Kiribati government has responded by including several special provisions in the Constitution, such as the designation of a Banaban seat in the legislature and the return of land previously acquired by the government for phosphate mining. Only around 300 people remain on Banaba. Despite being part of Kiribati, Banaba's municipal administration is by the Rabi Council of Leaders and Elders, which is based on Rabi Island, in Fiji. In 2006, Teitirake Corrie, the Rabi Island Council's representative to the Parliament of Kiribati, called for Banaba to secede from Kiribati and join Fiji.

COVID-19 pandemic[edit]

When the COVID-19 pandemic began in early 2020, Kiribati closed off its borders, to the extent that citizens living abroad were prevented from returning. The nation remained free of the infection and in late 2021, as the case rate seemed to be declining in many countries, the government considered relaxing restrictions. By that time, 33 percent of the nation's residents had been fully vaccinated against infection. In January 2022, a group of Kiribati citizens who had been living and travelling abroad as missionaries for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when the pandemic began returned to Kiribati on a chartered plane. Despite negative tests for the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 before and after arrival, and a quarantine period, 36 of the 54 passengers tested positive soon after their arrival. Within a few days, the viral infection had spread to more than 180 members of the community.[45]

See also[edit]

Bibliography[edit]

- Cinderellas of the Empire, Barrie Macdonald, IPS, University of the South Pacific, 2001

- Les Insulaires du Pacifique, Ian C. Campbell & Jean-Paul Latouche, PUF, Paris, 2001

- Kiribati: aspects of history, Sister Alaima Talu et al., IPS, USP, 1979, reprinted 1998

- A Pattern of Islands, Sir Arthur Grimble, John Murray & Co, London, 1952

- Return to the Islands, Sir Arthur Grimble, John Murray & Co, London, 1957

- A History of Kiribati: from the Earliest Times to the 40th Anniversary of the Republic, Michael Ravell Walsh, 2020 (Independently published).

- Stanton, W. R. (1975). The Great United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–1842. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520025578.

References[edit]

- ^ Cinderellas of the Empire, Barrie Macdonald, IPS, University of the South Pacific, 2001, p.1

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, "Kiribati"

- ^ I-Kiribati Ministry of Finance and Economic Development: "History" Archived 14 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Maude, H.E. (1959). "Spanish Discoveries in the Central Pacific: A Study in Identification". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 68 (4): 284–326.

- ^ "Circumnavigation: Notable global maritime circumnavigations". Solarnavigator.net. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ^ Samuel Eliot Morison (22 May 1944). "The Gilberts & Marshalls: A distinguished historian recalls the past of two recently captured pacific groups". Life magazine. Retrieved 14 October 2009.

- ^ Chambers, Keith S.; Munro, Doug (1980). "The Mystery of Gran Cocal: European Discovery and Mis-Discovery in Tuvalu". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 89 (2): 167–198.

- ^ Stanton 1975, pp. 212, 217, 219–221, 224–237, 240, 245–246.

- ^ Tyler, David B. – 1968 The Wilkes Expedition. The First United States Exploring Expedition (1838–42). Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society

- ^ The extensive report of the expedition has been digitized by the Smithsonian Institution. The visit to the Gilbert Islands (then called the Kingsmill Islands) is described in Chapter 2 in volume 5, pp. 35–75, 'Ellice's and Kingsmill's Group', http://www.sil.si.edu/DigitalCollections/usexex/

- ^ Very often, this name applied only to the southern islands of the archipelago, the northern half being designated as the Scarborough Islands. Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary. Springfield, Massachusetts: Merriam Webster, 1997. p. 594

- ^ "Tourism Authority of Kiribati" (PDF). Mauri – Kiribati, Tawara and Gilberts. 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ Whitmee, Samuel James (1871). A missionary cruise in the South Pacific being the report of a voyage amongst the Tokelau, Ellice and Gilbert islands, in the missionary barque "John Williams" during 1870. J. Cook & Co, Sydney.

- ^ Lovett, Richard (1899). The history of the London Missionary Society, 1795–1895. Vol. 1. H. Frowde, London.

- ^ "In the South Seas, by Robert Louis Stevenson".

- ^ a b c d In the South Seas (1896) & (1900) Chatto & Windus; republished by The Hogarth Press (1987), Part IV

- ^ Robert Louis Stevenson (1896). In the South Seas, Part V, Chapter 1. Chatto & Windus; republished by The Hogarth Press.

- ^ Osborne, Ernest (20 September 1933). "Stevenson's Bouse on Butaritari". IV(2) Pacific Islands Monthly. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ^ Fanny Stevenson incorrectly names the ship in The Cruise of the Janet Nichol among the South Sea Islands A Diary by Mrs Robert Louis Stevenson (first published 1914), republished 2004, editor, Roslyn Jolly (U. of Washington Press/U. of New South Wales Press)

- ^ Maude, H.E.; Leeson, Ida (December 1965). "The Coconut Oil Trade of the Gilbert Islands". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 74 (4): 396–437.

- ^ Dr Temakei Tebano & others (September 2008). "Island/atoll climate change profiles – Butaritari Atoll". Office of Te Beretitent – Republic of Kiribati Island Report Series (for KAP II (Phase 2). Archived from the original on 6 November 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ Robert Louis Stevenson (1896). In the South Seas, Part IV. Chatto & Windus; republished by The Hogarth Press.

- ^ WR Carpenter (PNG) Group of Companies: About Us, http://www.carpenters.com.pg/wrc/aboutus.html Archived 2014-02-01 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 12 December 2011.

- ^ Deryck Scarr: Fiji, A Short History, George Allen & Unwin (Publishers) Ltd., Hemel Hempstead, Herts, England, p. 122.

- ^ MBf Holdings Berhad: About Us, http://www.mbfh.com.my/aboutus.htm Archived 2017-05-08 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 12 December 2011.

- ^ The proceedings of H.M.S. "Royalist", Captain E.H.M. Davis, R.N., May–August, 1892, in the Gilbert, Ellice and Marshall Islands.

- ^ Resture, Jane. "TUVALU HISTORY – 'The Davis Diaries' (H.M.S. Royalist, ship's journal 1892)". Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ a b Teo, Noatia P. (1983). "Chapter 17, Colonial Rule". In Larcy, Hugh (ed.). Tuvalu: A History. University of the South Pacific/Government of Tuvalu. pp. 127–139.

- ^ a b c Maslyn Williams & Barrie Macdonald (1985). The Phosphateers. Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0-522-84302-6.

- ^ a b c Ellis, Albert F. (1935). Ocean Island and Nauru; Their Story. Sydney, Australia: Angus and Robertson, limited. OCLC 3444055.

- ^ a b c Macdonald, B. K. (1982). Cinderellas of the Empire: Towards a History of Kiribati and Tuvalu, Australian National University Press, Canberra.

- ^ Annexation of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands to his Majesty's dominions : at the Court at Buckingham Palace, the 10th day of November, 1915. Great Britain, Privy Council, Gilbert and Ellice Islands Order in Council, 1915 (Suva, Fiji : Government Printer). 1916.

- ^ (Imperial). (1875). "Pacific Islanders Protection Act, ss. 6–11". Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ "FORMERLY DISPUTED ISLANDS". U.S. Department of the Interior, Office of Insular Affairs. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007.

- ^ Maude, H. E., & Doran, E., Jr. (1966). The precedence of Tarawa Atoll. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 56, 269–289.

- ^ Williams, M., & Macdonald, B. K. (1985). The phosphateers: A history of the British Phosphate Commissioners and the Christmas Island Phosphate Commission. Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic.

- ^ "To the Central Pacific and Tarawa, August 1943—Background to GALVANIC (Ch. 16, p. 622)". Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ Nohlen, D, Grotz, F & Hartmann, C (2001) Elections in Asia: A data handbook, Volume II, p831 ISBN 0-19-924959-8

- ^ McIntyre, W. David (2012). "The Partition of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands" (PDF). Island Studies Journal. 7 (1): 135–146. doi:10.24043/isj.266.

- ^ Reilly Ridgell. Pacific Nations and Territories: The Islands of Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia. 3rd Edition. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1995. p. 95

- ^ US Department of State Background Note

- ^ "Kiribati profile – Timeline". BBC News. 23 June 2015.

- ^ "Taneti Maamau declared new president of Kiribati". Radio New Zealand. 10 March 2016.

- ^ "Kiribati: Pro-China President Taneti Maamau wins reelection bid | DW | 23.06.2020". Deutsche Welle.

- ^ Perry, Nick; Metz, Sam (27 January 2022). "COVID hits one of the last uninfected places on the planet". AP News. Retrieved 30 January 2022.