South Ronaldsay

| Scottish Gaelic name | Raghnallsaigh a Deas |

|---|---|

| Scots name | Sooth Ronalshee[1] |

| Old Norse name | Rǫgnvaldsey |

| Meaning of name | Old Norse for "Rognvald/Ronald's island" |

St Margaret's Hope on South Ronaldsay | |

| Location | |

| OS grid reference | ND449899 |

| Coordinates | 58°47′N 2°57′W / 58.78°N 2.95°W |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Orkney |

| Area | 4,980 hectares (19.2 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 22 [2] |

| Highest elevation | Ward Hill 118 metres (387 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | Orkney Islands |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 909[3] |

| Population rank | 16 [2] |

| Population density | 18.3 people/km2[3][4] |

| Largest settlement | St Margaret's Hope |

| References | [4][5][6] [7][8] |

South Ronaldsay (/ˈrɒnəltsiː/, also /ˈrɒnəldziː/, Scots: Sooth Ronalshee) is one of the Orkney Islands off the north coast of Scotland. It is linked to the Orkney Mainland by the Churchill Barriers, running via Burray, Glimps Holm and Lamb Holm.

Name[edit]

Along with North Ronaldsay, the island is named after St Ronald. The original name from which the English name derives, Rǫgnvaldsey, comes from Old Norse; Rǫgnvalds ("Ronald's") + ey ("island").

Geography and geology[edit]

With an area of 4,980 hectares (19.2 square miles), it is the fourth largest of the Orkney islands after The Mainland, Hoy and Sanday.[4] Ferries sail from Burwick on the island to John o' Groats on the Scottish mainland and from St Margaret's Hope to Gills Bay.[9]

South Ronaldsay's main village is St Margaret's Hope, Orkney's third largest settlement. It is named either after Margaret, Maid of Norway, the heir to the Scottish throne who died in Orkney age seven[10] or possibly St. Margaret. The village has a small blacksmith's museum and is known for its annual Boys' Ploughing Match. During this event young girls and boys dressed in dark jackets play the part of the horses and young boys using miniature ploughs compete with one another at ploughing a 4-foot square rig in the nearby sands.[9]

The cardinal points of the island are Ayre of Cara, by Churchill Barrier no. 4 (north), Grimness (east), Brough Ness, (south) and Hoxa Head, (west). The highest elevation is Ward Hill, which reaches 118 metres (387 ft). This name is common one in Orkney for the highest point on an island and comes from the historic use of these places used for the lighting of warning beacons.[11]

Prehistory[edit]

The island is known for the Neolithic Isbister Chambered Cairn, popularly known as the "Tomb of the Eagles". Discovered by Ronald Simison in 1958 in the south east of the island, 16,000 human bones and 725 bird bones were found at the site, the latter predominantly belonging to the White-tailed Sea Eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla). The evidence suggests that the human bodies had been exposed to the elements to remove the flesh before burial. The tomb was in continuous use for a millennium or more.[12][13]

The burnt mound at nearby Liddle, discovered by Simison in 1972, is the best example of a Bronze Age cooking place in Orkney. Made of flat slabs originally sealed with clay, the central stone trough would have been filled with water heated by stones using peat as a fuel. The building was probably roofless.[14]

There is a broch site at Howe of Hoxa in the north west that may have been the burial place of Thorfinn "Skullsplitter".[9]

History[edit]

In 1627 nine chapels were recorded on the island with some of the names hinting at the existence of Christian worship prior to the Norse conquest of Orkney. They were: Sant Androis at Woundwick, Our Ladie at Halcro, Sant Colmis at Loch of Burwick, Ruid chappell in Sandwick, Sant Tola [Olaf] in Wydwall, Sant Colme in Hoxay, Sant Margrat in the Howp, Sant Colmeis in Grymnes and Sant Ninian in Stow. The locations are all known although little physical evidence remains in several cases.[15]

In the late seventeenth century South Ronaldsay was described as "fertile in Corns and abounding with People".[16] Murdoch MacKenzie's 1750 map of the island indicates the site of lead workings near Grimness and a visitor in 1774 "saw several deep holes which I was informed were sunk in search of Lead ore" although only small quantities were mined.[15]

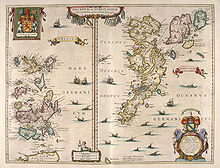

By the late eighteenth century South Ronaldsay was divided into two unequally sized parishes, St. Peter's covered the northern two thirds of the island while St. Mary's formed the southern third. St. Peter's church has a date stone of 1642 and appears on Blaeu's 1654 map. By 1793 the building had no roof and was "exposed to all the winds of heaven" but as probably repaired by 1801. A Pictish symbol stone was discovered in a window in the church. On one face of the slab is a mirror-case underlying part of an undecorated crescent and V-rod and on the other a crescent and V-rod, ornamented with scrollwork, below a decorated panel.[15]

During the 19th century the island's economy benefited from the herring fishing industry[17] and St Margaret's Hope became the main trading centre for the South Isles. In 1890 there were 20 shops and 18 tradesmen located there.[10]

Tomison's Academy was founded by William Tomison, a native of the island who became Governor of the Hudson's Bay Company. When it opened it had 170 pupils but the school closed in the 1960s. Tomison is buried nearby in the grounds of his former home, Dundas House.[18]

In 1991, the island was rocked by false allegations of widespread child abuse, as part of the worldwide Satanic panic, that saw nine children being removed from their families by police and social workers. The case was thrown out of court when it was found the social workers were using unorthodox interrogation techniques to force confessions from the children, who all denied the abuse.[19]

There are many well-preserved houses and other structures in the local vernacular style.

Local politics[edit]

The island is part of the "East Mainland, South Ronaldsay and Burray" ward, represented on the Orkney Islands Council by three independent councillors.[20] The local community council covers both South Ronaldsay and Burray.

Natural history[edit]

Microtus arvalis ronaldshaiensis is one of five varieties of the Orkney vole, a sub-species of the common vole found only in the Orkney islands. Larger than the common vole, it resembles the field vole but has shorter, paler fur.

The Orkney voles were introduced to the archipelago in Neolithic times. The oldest known radiocarbon-dated fossil of the Orkney vole is 4600 years BP, which marks the latest possible date of introduction.[21]

See also[edit]

- List of islands of Scotland

- List of Orkney Islands

- Alexander Carrick, sculptor of war memorial and linked to Saint Margaret's Hope

References[edit]

- Notes

- ^ "Map of Scotland in Scots - Guide and gazetteer" (PDF).

- ^ a b Area and population ranks: there are c. 300 islands over 20 ha in extent and 93 permanently inhabited islands were listed in the 2011 census.

- ^ a b National Records of Scotland (15 August 2013). "Appendix 2: Population and households on Scotland's Inhabited Islands" (PDF). Statistical Bulletin: 2011 Census: First Results on Population and Household Estimates for Scotland Release 1C (Part Two) (PDF) (Report). SG/2013/126. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 358–59.

- ^ "Orkney Placenames" Orkneyjar. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ^ Ordnance Survey: Landranger map sheet 7 Orkney (Southern Isles) (Map). Ordnance Survey. 2008. ISBN 9780319228135.

- ^ Anderson, Joseph (Ed.) (1893) Orkneyinga Saga. Translated by Jón A. Hjaltalin & Gilbert Goudie. Edinburgh. James Thin and Mercat Press (1990 reprint). ISBN 0-901824-25-9

- ^ Pedersen, Roy (January 1992) Orkneyjar ok Katanes (map) Inverness. Nevis Print.

- ^ a b c Wenham, Sheena "The South Isles" in Omand (2003) p. 212.

- ^ a b Wenham, Sheena "The South Isles" in Omand (2003) p. 211.

- ^ "Orkney Placenames - natural elements" Orkneyjar. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- ^ Hedges, J. 1990. Tomb of the Eagles: Death and Life in a Stone Age Tribe. New Amsterdam Books. ISBN 0-941533-05-0

- ^ "Isbister (Tomb of the Eagles) Chambered Cairn" Stonepages.com. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ^ "Liddle Burnt Mound" Stonepages.com. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ^ a b c "ORKNEY: O4. Paplay, South Ronaldsay" Archived 13 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine The Papar Project: RCAHMS. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ^ Wallace, J. (1693) A Description of the Isles of Orkney by Master James Wallace, published after his death by his son, to which is added, An essay concerning the Thule of the ancients (by Sir Robert Sibbald). Edinburgh. John Reid. Quoted by The Papar Project Archived 13 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine RCAHMS. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ^ Wenham, Sheena "Modern Times" in Omand (2003) p. 103.

- ^ Wenham, Sheena "The South Isles" in Omand (2003) pp. 212–13.

- ^ "Orkney 'abuse' children go home". BBC On this Day (April 4, 1991). 4 April 1991. Retrieved 13 July 2007.

- ^ "East Mainland, South Ronaldsay and Burray" Orkney.gov.uk. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ^ S. Haynes, M. Jaarola & J. B. Searle (2003). "Phylogeography of the common vole (Microtus arvalis) with particular emphasis on the colonization of the Orkney archipelago". Molecular Ecology. 12 (4): 951–956. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01795.x. PMID 12753214. S2CID 2819914.

no

- Bibliography

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 1-84195-454-3.

- Hedges, J. (1990) Tomb of the Eagles: Death and Life in a Stone Age Tribe. New Amsterdam Books. ISBN 0-941533-05-0

- Omand, Donald (ed.) (2003) The Orkney Book. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-254-9

Further reading[edit]

- Barthelmess, Isle Barbette (2004) A Celebration of Sunrise at the Tomb of the Eagles. Orkney Museums and Heritage. ISBN 978-0-9548862-0-2

- Picken, Stuart D.B.,The Soul of an Orkney Parish, The Kirkwall Press, Kirkwall, 1972.

- Lamb, Gregor, The Place-Names of South Ronaldsay and Burray, Bellavista Publications, Kirkwall, 2006.