Round World version of Tolkien's legendarium

The Round World Version is an alternative creation myth to the version of J.R.R. Tolkien's legendarium as it appears in The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings. In that version, the Earth was created flat and was changed to round as a cataclysmic event during the Second Age in order to prevent direct access by Men to Valinor, home of the immortals.[1] In the Round World Version, the Earth is created spherical from the beginning.

Tolkien abandoned the Round World Version before completion of The Lord of the Rings but later regretted this decision. He felt that postulating an ancient flat world detracted from the believability of his writings. He planned a new round world version, but only got as far as an outline. He continued to redraft his published works to make them compatible with a round world version for most of the rest of his life. His son Christopher, editing The Silmarillion which he published after Tolkien's death, considered adjusting the text to comply with Tolkien's wish to return to the Round World Version, but decided against it, not least because the story of the submerging of Númenor relies intrinsically on the Flat World cosmology.

History[edit]

Tolkien gives the fullest account of the creation myth in the Ainulindalë ("Music of the Ainur"). He wrote the original version in the 1930s, calling it the "Flat World Version" or later the "Old Flat World Version" after he had created a new flat world version. In 1946 he wrote the "Round World Version", intending this to be the published version. Tolkien sent both the "Old Flat World Version" and the "Round World Version" to Katharine Farrer (mystery novelist and wife of the theologian Austin Farrer) for review in 1948. Farrer replied to him in October strongly supporting the Flat World Version – "The hope of Heaven is the only thing which makes modern astronomy tolerable..."[2] Farrer seems to have influenced Tolkien to abandon the Round World Version, which he did before completing The Lord of the Rings, or even starting its last volume, The Return of the King.[3][4] Tolkien created a new manuscript from a heavily edited Old Flat World Version.[5] He then produced a final polished version with illuminated capitals.[3]

No version of the Ainulindalë was published during Tolkien's lifetime, but a heavily edited[3] version later formed the first chapter of the 1977 The Silmarillion edited by Tolkien's son Christopher.[5] The earliest version (not named Ainulindalë) was published in 1983 in The Book of Lost Tales volume 1.[6] The Old Flat World Version was included in the 1987 The Lost Road and Other Writings. Both the Round World Version and the New Flat World Version were included in the 1993 Morgoth's Ring. The latter is a more faithful reproduction of Tolkien's manuscript than the version in The Silmarillion.[1]

Tolkien also wrote a Round World Version of the Akallabêth ("The Downfall of Númenor"),[1] possibly in 1948 to match the Ainulindalë Round World Version.[7] This is an Atlantis-like story of the destruction of the island of Númenor, brought about by their deception by Sauron. This geographic change is part of the transition from flat to round world. Like Ainulindalë, Akallabêth was not published during Tolkien's lifetime, but it was included in The Silmarillion.[8]

As late as 1966 Tolkien was still attempting to make the Round World Version work across his body of work. In The Hobbit he has the Wood-elves lingering in the twilight of the Sun (Round World) instead of lingering in the twilight before the raising of the Sun (Flat World).[9]

Tolkien's dilemma[edit]

An internal problem: impossible to the Númenóreans[edit]

According to the lawyer and author on Tolkien Douglas Kane, the fundamental problem Tolkien had with the Flat World Version was that the Númenóreans, the ancestors of Men, were the means by which the legends of the earliest days were transmitted to later generations. Tolkien believed that the Númenóreans would understand that a flat Earth was impossible.[3]

An external problem: incredible to the ordinary reader[edit]

The Tolkien scholar John D. Rateliff takes a different view of the problem, writing that Tolkien had changed his mind about what an ordinary reader would be able to believe, or the extent to which that reader might be able to suspend their disbelief, in the face of a medieval cosmology. Rateliff wrote that [12]

Tolkien had come to believe that the average reader’s astronomical knowledge by the middle of the twentieth century was sufficient that the idea of a flat earth—circled by a little sun and moon that were glowing fruits and flowers from magical trees carried in flying boats, each of which, steered by an angel, sails in the sky from east to west before travelling back beneath the earth by night—simply won’t do.[12]

The horns of the dilemma[edit]

The Flat World Version was thus essentially unacceptable, whether internally or externally, requiring replacement.[12] But the story of the submerging of Númenor relies intrinsically on this cosmology. Many other dramatic moments would be lost or need serious revision to make a Round World Version consistent across all of the works in the Middle-earth legendarium.[3] Amongst the tales that would need revising, but for which Tolkien produced no alternative version, is the story of the Two Trees.[4] The Round World Version represents a major, concrete part of Tolkien's attempt to entirely rewrite the mythology of Middle-earth.[13] Rateliff comments that Tolkien had an "extremely good" grasp of the "cascading effects" of making a change in his legendarium; and that this change was uniquely awkward, as it stood at the junction of the myths from Valinor and the legends of Beleriand. Tolkien saw that he would have to rewrite the early tales that set out his cosmology, and stop work on the legends until the cosmology had been made fully consistent. In Rateliff's view, Tolkien "became convinced that he had to make changes he simply couldn’t bring himself to make",[12] and became stuck. As if this were not enough, in 1951 his publisher rejected The Silmarillion. Whether or not Tolkien could have resolved one or other of these issues, Rateliff writes, the two together "probably" ensured that The Silmarillion would not be published in his lifetime.[12]

The Round World Version of the Akallabêth was named by Tolkien The Drowning of Anadûnê. He described this as the "Man's version" possibly to distinguish it from the Elvish version in the Akallabêth and reconcile why there are two versions in the legendarium. Much as he would like to entirely abandon or heavily revise the Flat World Version, Tolkien writes that he cannot because it is already too embedded in the universe he has created.[4] Tolkien was attempting, but failing, to reinforce the sense of believability in his mythology by bringing it more into line with scientific knowledge of the history of Earth.[14][9] But the Round World Version generated as many problems as it solved, such as where now was the earthly paradise of Valinor to be placed.[14] The Tolkien scholar Verlyn Flieger described the attempt as "a 180% turn" and "'a fearful weapon' against his own creation".[15]

Choice for The Silmarillion[edit]

During preparation of The Silmarillion for publication, Christopher Tolkien was aware that his father had intended to update it to a new Round World Version. He considered editing the manuscripts to comply with this wish. In other respects, he had edited the stories to make them internally self-consistent and consistent with the already published canon.[3] Versions of The Silmarillion stories more closely following Tolkien's manuscripts were subsequently published by Christopher in The History of Middle-earth series of twelve books.[3]

Christopher decided against such an update because what his father had left was no more than an outline of his intentions. The earlier Round World Version was also no longer viable because by this stage it differed too greatly from already published works. The Silmarillion would either need some major rework of the text or else the change would introduce new inconsistencies.[3]

In-universe description[edit]

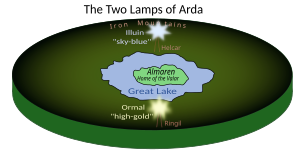

Christopher Tolkien described the Round World Version as "de-mythologised". As well as removing the flat Earth, the need for the Sun and Moon to be transported by mythical beings is removed. Also gone are the two enormous lamps that light the Earth before the creation of the Sun. The Sun is there from the beginning.[4]

In the Round World Version, the Earth was always round, and Arda was the name for the whole solar system instead of just the Earth. The Sun and the Moon were not the fruit of the Two Trees, but preceded the creation of the Trees. Instead, the Trees preserved the light of the Sun before it was tainted by Melkor.

The Moon is not created by Eru, the supreme being, as in the Flat World Version, but by Melkor, his chief antagonist, who tore it from the Earth. The Moon becomes Melkor's stronghold and because of this, it is moved further away from the Earth by the Valar to diminish Melkor's influence. Christopher Tolkien considers this more de-mythologising: the Moon is created after the Earth, and from a part of it, in accordance with the scientific paradigm.[16]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Kane 2009, p. 33.

- ^ Tolkien 1993, Ainulindalë: Farrer, quoted by Christopher Tolkien.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kane 2009, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d Whittingham 2008, p. 117.

- ^ a b Tolkien 1993, Ainulindalë.

- ^ Nagy 2013, p. 608.

- ^ Kane 2009, p. 243.

- ^ Tolkien 1977, Akallabêth.

- ^ a b Garbowski 2013, p. 425.

- ^ Carpenter 2023, letter 154 to Naomi Mitchison, 25 September 1954

- ^ Shippey 2005, pp. 324–328.

- ^ a b c d e Rateliff 2020.

- ^ Nagy 2013, p. 609.

- ^ a b Curry 2013, p. 139.

- ^ Flieger, Verlyn (2023). "'A Fearful Weapon'". Mythlore. 42 (1). Article 10.

- ^ Whittingham 2008, pp. 117–118.

Sources[edit]

Primary[edit]

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (2023) [1981]. The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien Revised and Expanded Edition. New York: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-35-865298-4.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1993). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). Morgoth's Ring. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Ainulindalë. ISBN 0-395-68092-1.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Silmarillion. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2.

Secondary[edit]

- Curry, Patrick (2013) [2007]. "Earth". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 138–139. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- Garbowski, Christopher (2013) [2007]. "Middle-earth". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 422–428. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- Nagy, Gergely (2013) [2007]. "Silmarillion, The". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 608–612. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- Kane, Douglas Charles (2009). Arda Reconstructed: The Creation of the Published Silmarillion. Associated University Presses. ISBN 978-0-9801496-3-0.

- Rateliff, John D. (2020). "The flat Earth made round and Tolkien's failure to finish The Silmarillion". Journal of Tolkien Research. 9 (1).

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- Whittingham, Elizabeth A. (2008). The Evolution of Tolkien's Mythology. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-3281-3.