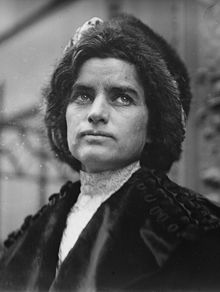

Kate Barnard

Kate Barnard | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st Oklahoma Commissioner of Charities and Corrections | |

| In office 1907–1915 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | William D. Matthews |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Catherine Ann Barnard May 23, 1875 Geneva, Nebraska, U.S. |

| Died | February 23, 1930 (aged 54) Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic Party |

| Occupation | Social reformer, politician, teacher |

| Known for | First woman elected to statewide office in Oklahoma |

Catherine Ann "Kate" Barnard (May 23, 1875 – February 23, 1930) was the first woman to be elected as a state official in Oklahoma, and the second woman to be elected to a statewide public office in the United States,[1] in 1907. She served as the first Oklahoma Commissioner of Charities and Corrections for two four-year terms, the only position that the 1907 Oklahoma Constitution permitted a woman to hold.

Before being elected to office, Barnard had worked as a teacher and in clerical patronage positions in the territorial government.[2] She was also heavily involved in charity work.

Early life[edit]

Barnard was born in Geneva, Nebraska, on May 23, 1875, to John P. and Rachel Sheill Barnard.[2] Her mother died when she was two and the family was living in Kansas.[2] She was raised by relatives until 1891, when she moved to Newalla, Oklahoma, where her father, a jack-of-all-trades, had a land claim. [a]She lived alone on the claim for two years while he lived and worked in Oklahoma City. She moved to Oklahoma City in 1895, attended St. Joseph's Academy (a Catholic school), obtained a teaching certificate, and taught until 1902.[4]

Charity work[edit]

After she quit teaching, Barnard took a business course, then became a secretary for the territorial legislature in Oklahoma City. In 1904, she was selected from among 500 applicants to be a "territorial hostess" at the St. Louis World's Fair. While in St. Louis, she met Jane Addams and others who were active in social reform movements. She also was exposed to big-city slum life, crime and other related social ills. From then on, she became a reformer.[4]

Prior to Oklahoma statehood, Barnard was involved in aid and charity work in Oklahoma City and was the head of the union-label organization in Oklahoma. She also participated in the Farm-Labor meetings of 1906 in Shawnee which drafted the "Shawnee Demands" that later formed the basis of the soon-to-be-drafted Oklahoma state constitution.

Elected Charities and Corrections Commissioner[edit]

Compulsory education, child labor, abuse of prisoners[edit]

After her election as the Charities and Corrections Commissioner, she was a key player in the enactment of the compulsory education laws, state support of poor widows dependent on their children's earnings, and statutes implementing the constitutional ban on child labor. She also was an advocate for working Oklahomans through the work she did in securing legislation aimed at eradicating unsafe working conditions and the blacklist of union members. She was one of the few public officials who dared to cry out against the abuse of Native American children. Barnard relied on her stirring speeches to reach the public and convince the political powers of the need for increased federal protection for all Five Tribes' members.

Some[who?] have said that her most important action may have been when she uncovered the abusive treatment of Oklahoma prisoners who were being held in Kansas prisons under contract, which included forced labor in coal mines and torture. She was featured as an anti-suffragist in Good Housekeeping who discussed her work uncovering the abuses of Oklahoma prisoners.[5] Her work and the pressure she put on Oklahoma's first Governor, Charles N. Haskell, resulted in the return of the prisoners to Oklahoma and the construction of the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester, Oklahoma.

End of her political career[edit]

Her political career ended during her second term in office, after she began to advocate on behalf of Indian wards who were being cheated out of their land as a result of grafting. During this time, her office produced the first official governmental investigative report of the Osage Indian murders.[6] Her work on behalf of Indian children raised the ire of William H. Murray and other prominent Oklahoma businessmen and officials who convinced the state legislature to defund her office. Wilma Mankiller's 1993 book, Mankiller, A Chief and Her People, on page 173 quotes Barnard: "I have been compelled to see orphans robbed, starved, and burned for money. I have named the men and accused them and furnished the records and affidavits to convict them, but with no result. I decided long ago that Oklahoma had no citizen who cared whether or not an orphan is robbed or starved or killed - because his dead claim is easier to handle than if he were alive."

Later life, death, and legacy[edit]

During the rest of her life, Barnard continued to live in Oklahoma (often traveling to Colorado and other states during the summer due to her severe health problems) and she died on February 23, 1930, in Oklahoma City (where she was found dead in a hotel bathroom). She was buried in Oklahoma City (in a grave that was not marked until the 1980s), but today a bronze statue of her is on display on the first floor of the Oklahoma State Capitol. She was inducted in the Oklahoma Women's Hall of Fame in 1982.

Electoral history[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2023) |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Kate Barnard | 134,300 | 55.2 | New | |

| Republican | Haxel Tomlinson | 98,960 | 40.7 | New | |

| Socialist | Kate Richards O'Hare | 9,615 | 3.9 | New | |

| Democratic gain from | Swing | N/A | |||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Kate Barnard (incumbent) | 120,703 | 51.05% | |

| Republican | Kate H. Biggers | 91,907 | 38.86% | |

| Socialist | Winnie Branstetter | 23,872 | 10.09% | |

| Total votes | 236,482 | 100.0 | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

Notes[edit]

See also[edit]

- Jeannette Rankin first woman elected to the United States Congress

- Oklahoma Constitution

Sources[edit]

- Katie Barnard "Our Good Angel" (information on the statue erected in her honor)

- One Woman's Political Journey: Kate Barnard and Social Reform 1875-1930 by Lynn Musslewhite and Suzanne Jones Crawford

- "Barnard, Kate." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006. Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service. 11 Mar. 2006

- Our Heroine, Kate Barnard (Red Flag Press)

- Leavitt, Julian (February 1912), "The Man In The Cage", The American Magazine, LXXIII (5), The Phillips Publishing Co.

References[edit]

- ^ See Laura J. Eisenhuth

- ^ a b c Musslewhite, Lynn, and Suzanne Jones Crawford, "Barnard, Catherine Ann (1875-1930)," Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture Archived 2010-05-31 at the Wayback Machine (accessed May 7, 2010).

- ^ Thoburn, Joseph B. A Standard History of Oklahoma. p. 1329. 1916. Accessed August 5, 2020.

- ^ a b *"Saint Kate." Oklahoma Today. Archived 2014-08-19 at the Wayback Machine Logan, Jim. December 2012. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ^ Martin, I.T. (July 1912). "Concerning Some of the Anti-Suffrage Leaders". Good Housekeeping. 55: a80–a83. ProQuest 1934095268 – via Proquest: Women's Magazine Archive.

- ^ Stanley, Tim (October 18, 2023). "Kate Barnard was one of the first to look into the Osage Reign of Terror, and it cost her". Tulsa World. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ "General Election - September 17,1907" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 25, 2020. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ "Official Vote". The McAlester News-Capital. December 16, 1910. p. 9. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

External links[edit]

- Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture - "Barnard, Kate"

- Kate Barnard at Find a Grave

- "Saint Kate." Oklahoma Today. Logan, Jim. December 2012. Retrieved August 11, 2014.