Brunswick, Victoria

| Brunswick Melbourne, Victoria | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Heritage buildings on Sydney Road, Brunswick | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 37°46′00″S 144°57′46″E / 37.7667°S 144.9628°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 24,896 (2021 census)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| • Density | 4,790/km2 (12,400/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 3056 | ||||||||||||||

| Elevation | 50.4 m (165 ft)[2] | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 5.2 km2 (2.0 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Location | 5 km (3 mi) N of Melbourne | ||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | City of Merri-bek | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Brunswick | ||||||||||||||

| Federal division(s) | Wills | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

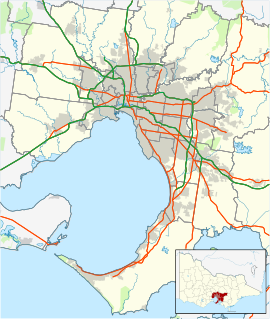

Brunswick is an inner-city suburb in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 5 km (3.1 mi) north of Melbourne's Central Business District, located within the City of Merri-bek local government area. Brunswick recorded a population of 24,896 at the 2021 census.[1]

Traditionally a working class area noted for its large Italian and Greek communities, Brunswick is currently known for its bohemian culture and strong arts and live music scenes. It is also home to a large student population owing to its proximity to the University of Melbourne and RMIT University, the latter of which has a campus in the suburb. Brunswick's major thoroughfare is Sydney Road, one of Melbourne's major commercial and nightlife strips. It also encompasses the northern section of Lygon Street, synonymous with the Italian community of Melbourne, which forms its border with Brunswick East.

Brunswick takes its name from George IV and the city of Brunswick, Germany, which lay within his ancestral Kingdom of Hanover. It is bordered to the south by the suburbs of Princes Hill and Parkville, to the east by Brunswick East, to the north by Coburg and to the west by Brunswick West.

History[edit]

Early history[edit]

Brunswick is in the area known as Iramoo by the Aboriginal people who inhabited and hunted in it. It was occupied by the Wurundjeri people who spoke the Woiwurrung dialect. White settlement began in the 1830s, with Assistant Surveyor Darke surveying the area under the instruction of Robert Hoddle. North and south boundaries were drawn up, running in an east–west direction between Moonee Ponds Creek and Merri Creek. These boundaries would become Moreland Road and Park Street, respectively. A narrow road was surveyed down the centre to service what were intended to be agricultural properties, which would eventually become the major thoroughfare of Sydney Road. Ten allotments were drawn up on each side of this road, with each block of land running all the way to either Moonee Ponds Creek or Merri Creek. These wide strips of land are still reflected in the current street layout.

The land was sold at auction in Sydney and attracted speculators, many of whom would never see the land they purchased. Only one original buyer, James Simpson, settled on his land. Simpson subdivided his land and marked out two streets, Carmarthon Street (later Albert Street) and Landillo Street (later Victoria Street). Because the land was too marshy he left the area in 1859 with much of the land unsold.

In 1841 two friends, Thomas Wilkinson and Edward Stone Parker, bought land from one of the original buyers. Parker soon left but Wilkinson stayed on and subdivided his land for sale or rent. He marked two roads which would eventually become extensions of the roads marked out by Simpson. Wilkinson named the streets Victoria Street (after Queen Victoria) and Albert Street (after her husband Prince Albert).

Wilkinson's office opened in 1846, taking on the name of Wilkinson's estate and thus establishing the name of the whole area.

In October 1842, Miss Amelia Shaw became the licensee of the first hotel in the area, the Retreat Inn. The hotel also had a weighbridge so bullock drivers could refresh themselves whilst their wagons were weighed. The establishment was rebuilt in 1892 and renamed the Retreat Hotel; it still stands today.

Also in 1842, work began on a new road along the central surveyors' division. The road was originally known as Pentridge Road; it led to the bluestone quarries of Pentridge (now Coburg). In 1843, William Lobb established a cattle farm on his allotment and the area became known as Lobb's Hill. A laneway down the side of his property, originally called Lobb's Lane, would later be named Stewart Street.

In 1849, one of the original land purchasers, Michael Dawson, completed work on an ivy-covered mansion on his property called Phoenix Park. The property was named after Phoenix Park near Dublin, Ireland. Dawson cited his address not as Brunswick but as Philiptown, after a town in Ireland which has since reverted to its original name of Daingean. Philiptown eventually grew into a village along the track which led from Phoenix Park to Sydney Road. This track was later named Union Street.

Goldrush era[edit]

Henry Search opened a butcher's shop in 1850, on the south-west corner of Albert Street and Sydney Road. This was the first retail establishment in Brunswick. By 1851, gold diggers began making their way through the area, on their journey from the populous suburbs of Fitzroy and Collingwood. Brunswick provided a convenient place for lunch, before the diggers reached the beginnings of the roads to the goldfields, near present-day Essendon. A small village sprang up to meet the needs of the travellers, near the present day Cumberland Arms Hotel. The village included a tent market, described as being like a bazaar, where miners could buy goods needed for the goldfields. Brunswick Post Office opened on 1 January 1854.[3]

In 1859, Wilkinson established the area's first newspaper, The Brunswick Record, which changed its name in 1858 to The Brunswick & Pentridge Press.[citation needed]

By 1857, the local population was estimated at 5000. The Brunswick Municipal Council was established in that year at the Cornish Arms Hotel, which still stands. The first municipal chambers were established in 1859 on Sydney Road at Lobb's Hill, between Stewart and Albion Streets.[citation needed] The present Brunswick Town Hall is an imposing Victorian edifice built in 1876 on the corner of Dawson Street and Sydney Road, near the centre of Brunswick.

In the 1850s, quarries and a large brickworks established in Brunswick, using the local clay and bluestone, quickly became the largest industry in the area. In 1884 the first Brunswick railway line opened, running from North Melbourne to Brunswick and Coburg. The line ran directly into the Hoffmans Brickworks, reflecting the importance of the brick-making industry to the local community. Prior to World War I, Brunswick was the "brickyard capital of Victoria". Remnants of the brickyards are still visible in some parts of Brunswick but most of the yards have long been converted to residential housing or parks.[4] A few years later – in 1887 – a cable tram line was laid along Sydney Road.

Post-goldrush era[edit]

In 1908, Brunswick officially became a city. Textiles became a large industry in the area in the early decades of the 20th century, while quarrying declined with the depletion of reserves.[citation needed] In the latter half of the 1920s, thousands of Brunswick residents worked in the textile and rope manufacturing industries.[5] By 1930, there were 300 factories in Brunswick employing over 6,000 workers.[5]

"Free Speech" campaigns occurred in Brunswick during 1933, as protestors countered the actions of police who sought to prevent "street meetings" of communists.[6][7] On 19 May 1933, two incidents occurred on Sydney Road.[8] Large numbers of police officers were in the area to prevent expected street meetings and, when Reginald Patullo was spotted addressing a crowd from the roof of a tram, the police gave chase.[8] As Patullo attempted to evade capture, one of the pursuing officers tripped and shot Patullo in the thigh.[8]

On the same night, a "well-dressed young man" appeared in a cage on the back of a lorry.[8] He used a megaphone to address the crowd and the cage itself bore slogans such as "We want free speech". Police dispersed the crowd and the young man was eventually freed and then arrested.[8] By June 1933, Brunswick residents and local council members were criticising the police action, and Councillor Wylie stated: "Without any discretion, mounted troopers drove men, women, and children off the footpaths in Sydney road into the path of traffic on Friday nights."[7]

Post-World War II era[edit]

In the post-World War II era, Brunswick became the home of a large number of migrants from southern Europe, particularly from Italy, Greece and Malta. More recently, migrants from Lebanon, Turkey and other countries have arrived. The brickworks and much of the textile industry also began to close as gentrification accelerated in the 1990s.[citation needed] Many old buildings were renovated and new residential developments begun during this period.

In 2004, Brunswick and nearby Carlton were the location of several murders in what has been widely reported in Melbourne's media as an "underworld war".

Commerce[edit]

Commercial activity is mainly centred on Sydney Road and Lygon Street in neighbouring Brunswick East. While separated from the tourist strip in Carlton, northern Lygon Street has a substantial number of restaurants. Barkly Square, extensively renovated in 2014, is Brunswick's major covered shopping centre, located on the east side of Sydney Road, close to Jewell railway station, although there is a wide variety of supermarkets to be found all along the Sydney Road strip.

Demographics[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 16,576 | — |

| 2001 | 19,867 | +19.9% |

| 2006 | 20,780 | +4.6% |

| 2011 | 22,764 | +9.5% |

| 2016 | 24,473 | +7.5% |

| 2021 | 24,896 | +1.7% |

In the 2021 census, there were 24,896 people in Brunswick.

- The most common ancestries were English 31.1%, Australian 25.2%, Irish 15.5%, Scottish 10.8% and Italian 10.4%.

- 66.4% of people were born in Australia. The next most common countries of birth were England 3.6%, New Zealand 3.0%, Italy 2.6%, Greece 2.5% and United States of America 1.3%.

- 72.9% of people spoke only English at home. Other languages spoken at home included Greek 4.5%, Italian 3.9%, Mandarin 1.8%, Arabic 1.8% and Spanish 1.4%.

- The most common responses for religion were No Religion 61.2%, Catholic 13.8%, Eastern Orthodox 5.6%, Not stated 4.8% and Islam 2.9%.

Politics[edit]

During the Great Depression in 1933, Brunswick was the site of free speech meetings by members of the Unemployed Workers Movement, who were harassed and suppressed by the police.[citation needed] The young artist Noel Counihan played a significant part in this campaign. A Free Speech memorial was built in 1994 outside the Mechanics' Institute on the corner of Sydney and Glenlyon Roads to commemorate the free speech fights. Counihan's work as an artist and local resident is also commemorated by the Counihan Gallery in the Brunswick Town Hall, at the corner of Sydney Road and Dawson Street, run by the City of Merri-bek.

Brunswick has long been a stronghold of left-wing politics in Melbourne, with the federal and state parliamentary seats held by the Australian Labor Party with very comfortable margins. In the 21st century these margins have been encroached upon by the increasingly popular Australian Greens, who at the 2016 Australian federal election polled a majority of the two-party-preferred vote against the Australian Labor Party in every booth in Brunswick.[9] However, as well as the "mainstream" left, Brunswick and nearby suburbs have for many years been a holdout of other left-wing parties, radical socialists, and anarchists.

In 2018 the Victorian state electoral district of Brunswick elected a Greens member, Tim Read, for the first time. He was re-elected in 2022 with an increased margin of 13.5%, making Brunswick a safe seat for the Greens.

Brunswick falls into the local City of Merri-bek's South Ward; at the 2020 election, the South Ward elected two Greens (James Conlan and Mark Riley) and one Labor councillor (Lambros Tapinos). James Conlan would later leave the Greens in February 2023.[10]

The Brunswick Progress Association, formed in 1905, has had an active role in representing residents, particularly on local issues to Merri-bek Council, but also at the state and federal levels.

Culture[edit]

In the 1980s, Brunswick's major nightspot was the Bombay Rock, a notoriously dangerous venue that saw considerable violence between ethnic groups.[citation needed] It was featured in the 1991 movie Death In Brunswick and destroyed by a fire in the mid-1990s.[citation needed]

The Sarah Sands Hotel has hosted tours from a number of local and international acts, mostly punk, skinhead, goth or alternative in nature. By 2017, it was again for sale.[citation needed]

Brunswick was the location of the "Brunswick Massive" art collective,[when?] which was run by local youths involved in Australian Hip Hop and Electronic Music events.

The Sydney Road Street Party, held annually in late February, is a major event in the suburb, during which a large proportion of Sydney Road is closed to all traffic. The festival is a prelude to the Brunswick Music Festival, held in March, featuring blues, roots, and world music.

Sport[edit]

Brunswick has two soccer clubs, Brunswick Juventus and Brunswick City, but Moreland United, Moreland City and Essendon Royals also have strong links to the suburb. There are two cricket clubs,(Brunswick Cricket Club, and Royal Park). The Brunswick Cricket Club, located at Gillon Oval, has a long history dating back to the 1860s and for the last 80 years has been part of the Victorian Sub-District Cricket Association. There is a tennis club (West Brunswick, which is actually located at Raeburn Reserve) and three Australian Rules football clubs. The main sites for sporting activity in Brunswick are focused around Clifton and Gilpin Park and the Gillon Oval, though there are many other ovals and pitches around the suburb. A hockey ground is located at Brunswick Secondary College. The hockey ground is owned by Brunswick Hockey Club.[11] The Brunswick Velodrome is in Brunswick East. Brunswick Athletic Club has been operating since 1953, competes in the North West Region of Athletics Victoria and has produced athletes who have represented Victoria and Australia. West Brunswick Football Club, North Old Boys Football Club and North Brunswick compete in the VAFA. Brunswick Netball Club is for all ages. The Brunswick Junior Football Club is based at Gillion Oval, West Brunswick. The North Brunswick Junior Football Club is based at Allard Park, East Brunswick. Both of these teams play in the Yarra Junior Football League. The Brunswick Netball Club is also based at Gillion Oval. The Brunswick Bowling Club is located in East Brunswick at 104-106 Victoria Street. The Brunswick Trugo Club is in Temple Park, at 29 Hodgson Street.

Facilities and services[edit]

Among the most notable, popular and long-standing of Brunswick's community facilities is the Brunswick City Baths in Dawson Street, opening in 1914. After protracted and expensive renovations from 2012, it reopened in 2014 with remodelled change rooms, indoor and outdoor heated pools and children's indoor play pool, fitness program rooms, steam room and sauna, spa and gymnasium. It is owned by Merri-bek Council and managed by the YMCA.

The Counihan Gallery is in the Brunswick Town Hall building which also housed the Brunswick Library, part of Merri-bek City Libraries, during the library's renovation in 2013–14. Certain municipal administrative functions still operate from the Brunswick Town Hall, while the former council offices are now used by community organisations.

While several of Brunswick's schools[which?] were sold off by the Kennett Government in the 1990s for private housing, the former Brunswick Secondary College building on Victoria Street was saved[citation needed] and has found a new use as the Brunswick Business Incubator, run by the economic development unit of Merri-bek Council.

Brunswick has a large number of social service agencies, from large Commonwealth corporate providers such as Centrelink, local government services and community-based organisations. Among the most notable are the two services for asylum seekers and refugees, the Asylum Seeker Welcome Centre and Foundation House.[citation needed]

Education[edit]

The first state-run kindergarten opened in Brunswick in 1907 by Emmeline Pye who worked at the Central Brunswick Training School.[12]

Brunswick North Primary School in Albion Street is the only government primary school within the boundaries of Brunswick,[citation needed] residents of the suburb have access to four additional primary schools in the vicinity: Brunswick South Primary School, Brunswick East PS (in Brunswick East), Brunswick South West PS and Brunswick North West PS, as well as two Catholic primary schools. There are two government secondary schools (Brunswick Secondary College and the Sydney Road Community School), a Catholic secondary school and a Maronite Catholic college. There is a campus of RMIT University focusing on Textiles and Printing in Dawson Street.

Brunswick East High School, which had been located on Albert Street, was closed permanently due to low student enrolments in 1992 and demolished and replaced by Rendazzo Park and townhouses. It had initially opened as Brunswick Domestic Arts School for Girls in the 1920s.[13]

Public open space[edit]

The main areas of open space in Brunswick are on its western edge, comprising several recreational areas that almost combine into a single space: the Alex Gillon Oval, Raeburn Reserve, Brunswick Park, Clifton Park and Gilpin Park. These areas are separated by Victoria and Albert Street. The remaining open spaces within Brunswick are small to tiny 'pocket parks' and reserves. The most notable are Temple Park, Warr Park and Randazzo Park, the latter having won awards for its contemporary landscape design. The southern edge of Brunswick faces directly onto Royal Park and Princes Park, which are large areas of regionally-significant open space in the suburbs of Parkville and Carlton North. Though not actually within Brunswick, there is good access to the Merri and Moonee Ponds Creeks, which are linear open spaces with bike paths along them, in Brunswick East and Brunswick West respectively.

Places of worship[edit]

Brunswick's diverse religious communities have many places of worship. Various Christian denominations have prominent churches, including Anglican, Serbian Orthodox (located in Brunswick East), Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholic, Baptist, and Uniting Church. Other Christian groups with places of worship are the Church of the Latter Rain and Jehovah's Witnesses. There are also two mosques and a Buddhist centre. Most of these places of worship are located along Sydney Road or its immediate hinterland.

| Denomination |

|

Photo | Website |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anglican | Christ Church Brunswick, 8-10 Glenlyon Road |  |

Website |

| Serbian Orthodox | Holy Trinity, 1 Noel Street |  |

Website |

| Greek Orthodox | St Vasilios, 15 Staley Street | Website | |

| Greek Orthodox | St Eleftherios, 279 Albion Street | ||

| Roman Catholic | St Ambrose, 287 Sydney Road |  |

Website |

| Baptist | Brunswick Baptist Church, 491 Sydney Road |  |

Website |

| Uniting Church | Brunswick Uniting Church, 214 Sydney Road |  |

Website |

Transport[edit]

The area is among the best-served by public transport in Melbourne.

Bus[edit]

Seven bus routes service Brunswick:

- 503 : Essendon station – Brunswick East via Albion Street. Operated by Dysons.[14]

- 504 : Moonee Ponds Junction – Clifton Hill station via East Brunswick. Operated by Dysons.[15]

- 506 : Moonee Ponds Junction – Westgarth station via Brunswick. Operated by Dysons.[16]

- 508 : Alphington station – Moonee Ponds Junction via Northcote and Brunswick. Operated by Dysons.[17]

- 509 : Brunswick West – Barkly Square Shopping Centre via Hope Street and Sydney Road. Operated by Dysons.[18]

- 510 : Essendon station – Ivanhoe station via Brunswick, Northcote and Thornbury. Operated by Kinetic Melbourne.[19]

- Night Bus 951 : Brunswick station – Glenroy station via West Coburg (operates Saturday and Sunday mornings only). Operated by Ventura Bus Lines.[20]

Cycling[edit]

Brunswick itself is relatively flat and is ideal for cycling. Brunswick East is bounded by the Merri Creek Trail, and Brunswick West by the Moonee Ponds Creek Trail, though neither of these can be described as flat. The Upfield Bike Path follows the Upfield railway line from Fawkner, through Coburg and Brunswick, joining the Capital City Trail at Park Street. Streets in Brunswick vary, from too narrow for two cars to pass, to reasonably wide. Not all of the wider streets have cycle lanes, though even riding in lanes in the narrower street often means riding close to parked cars, presenting a significant hazard to cyclists from opening car doors.

Train[edit]

Three railway stations service Brunswick: Jewell, Brunswick and Anstey stations, all located on the Upfield line.

Tram[edit]

Five tram routes service Brunswick:

, which travels along Sydney Road, Royal Parade and Elizabeth Street to Flinders Street railway station, past University of Melbourne campuses, hospitals and the Queen Victoria Market.

, which travels along Sydney Road, Royal Parade and Elizabeth Street to Flinders Street railway station, past University of Melbourne campuses, hospitals and the Queen Victoria Market. and

and  to Toorak, travelling along Lygon Street.

to Toorak, travelling along Lygon Street. , which travels through Royal Park and to the city from nearby Brunswick West.

, which travels through Royal Park and to the city from nearby Brunswick West. , traveling down Nicholson Street in nearby Brunswick East past Parliament House and Southern Cross railway station.

, traveling down Nicholson Street in nearby Brunswick East past Parliament House and Southern Cross railway station.

Landmarks and notable places[edit]

The most prominent structures in Brunswick are the heritage listed chimneys of Hoffmann's brickworks on Dawson Street. At their base, one of the brick kilns has been preserved, though the remainder of this site has been redeveloped as medium-density attached housing and low-rise apartment blocks. Other landmark buildings are the many churches along Sydney Road like Brunswick Baptist Church, the Brunswick Tram Depot, and the large bluestone warehouses in Colebrook Street.

Of the newer structures, the four new buildings at the RMIT University campus on Dawson Street are of notable contemporary character, each having its own unique architectural style, with two buildings by noted Melbourne architect John Wardle. The Brunswick Community Health Centre, on Glenlyon Road, completed in the late 1980s, presents a collection of eclectic, differently coloured forms juxtaposed on a small site. It was designed by Melbourne architecture firm Ashton Raggatt McDougall, who have since become internationally prominent.

Being one of Melbourne's oldest suburbs, Brunswick has a large number of places of heritage significance, in the form of individual buildings as well as urban conservation precincts covering entire streets or substantial parts of them.

Notable people[edit]

Sister cities[edit]

Brunswick has more Greeks of Laconian origin than anywhere else in Australia. The president of the Greek Community first suggested a sister city connection between Sparta and Brunswick in 1970. The sistership protocols were signed in 1987. A party comprising the Mayor of Sparta and eight dignitaries came to Brunswick for the official function in 1988, at which Talbot Street, (off Sydney Road, one block north of Victoria Street) was pedestrianised and renamed Sparta Place in recognition of the political and cultural link between the two places.[21] In 2005, Sparta Place was significantly remodelled.

See also[edit]

- City of Brunswick – Brunswick was previously within this former local government area.

- Death in Brunswick – a 1991 film set in Brunswick, starring Sam Neill, Zoe Carides and John Clarke.

- Janis and Saint Christopher – a 2013 urban fantasy e-novel set in Brunswick that features Janis Joplin.[22]

- Kick (TV series) – a 2007 SBS series set in Brunswick.

- Downs & Son – an early 20th century rope manufacturing factory in Brunswick, which remains the most intact rope works in the suburb.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Brunswick (Vic.) (Suburbs and Localities)". 2021 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ "Map of point 144.96, −37.767 near Sydney Road – Bonzle Digital Atlas of Australia". maps.bonzle.com. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 19 July 2007.

- ^ "Post Office List". Phoenix Auctions History. Archived from the original on 14 September 2023. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ O'Donnell, William F. (1999). "The Brunswick Baths". In Folk-Scolaro, Francesca (ed.). Transport in Brunswick 1839–1995. Brunswick, Australia: Brunswick Community History Group. ISBN 0-9587742-5-0.

- ^ a b "Millers Rope Works (Former, now RMIT University)" (PDF). Merri-bek City Council. March 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ "STREET MEETING STOPPED". The Argus. Melbourne. 22 April 1933. p. 22. Archived from the original on 14 September 2023. Retrieved 11 October 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b ""BATTLES" IN BRUNSWICK". The Argus. Melbourne. 9 June 1933. p. 5. Archived from the original on 14 September 2023. Retrieved 11 October 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c d e "MAN SHOT IN THIGH". The Argus. Melbourne. 20 May 1933. p. 21. Archived from the original on 14 September 2023. Retrieved 11 October 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "House of Representatives division information". Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ^ Waters, Cara (7 February 2023). "Merri-bek councillor resigns from Greens in solidarity with Lidia Thorpe". The Age. Archived from the original on 24 February 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ "Brunswick Hockey Club". Archived from the original on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ Factor, J., "Emmeline Pye (1861–1949)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, archived from the original on 17 February 2024, retrieved 18 February 2024

- ^ Heath, Tamara (2 November 2015). "Albert St Learning Centre Lives on in Book". Moreland Leader.

- ^ "503 Essendon - East Brunswick via Albion Street". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ "504 Moonee Ponds - Clifton Hill via East Brunswick". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ "506 Moonee Ponds - Westgarth Station via Brunswick". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ "508 Alphington - Moonee Ponds via Northcote & Brunswick". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ "509 Brunswick West - Barkly Square SC via Hope St & Sydney Rd". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ "510 Essendon - Ivanhoe via Brunswick & Northcote & Thornbury". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ "951 Night bus: City - Moonee Ponds - Brunswick West - Pascoe Vale - Glenroy". Public Transport Victoria.

- ^ Efstratiades, T. (1994), The Greeks in Brunswick, in Penrose, H. (Ed) Brunswick: One history, many voices, South Melbourne:Victoria Press, p. 269

- ^ Magnusson, Michael. "Edge of Fantasia". Gay News Network. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

Note: Moreland Council demographic data – look for the page numbers in the text of the document (centre, bottom etc.) as these are out of sync with the pdf page-numbering.

Further reading[edit]

- Barnes, Les (Ed)(1987) It Happened in Brunswick: 1837–1987, Brunswick: Brunswick Community History Group (ISBN 0-9587742-0-X)

- Brunswick Community History Group (2005) Brunswick Green: Historic Parks in Moreland, Brunswick: Brunswick Community History Group with Moreland City Council

- Brunswick Community History Group (1993) A Walk Along The Upfield Line, Brunswick: Brunswick Community History Group (No ISBN)

- Cunningham, L. and Burchell, L. (4th ed, 1999) Brunswick's Hotels, Brunswick: Brunswick Community History Group (No ISBN)

- Eckersall, K. (2006) The Pillars of Our Land: Brunswick Citizen Pioneers, Brunswick: Brunswick Community History Group (ISBN 0-9587742-9-3)

- Folk-Scolaro, F. (Ed)(2002) Faith of Our Fathers: Churches of Sydney Road, Brunswick, Brunswick: Brunswick Community History Group (ISBN 0-9587742-6-9)

- Himbury, A (2000) "As long as you could see the Hoffman's Chimneys you wasn't lost": Saving Brunswick's Brickworks, Brunswick: Save the Brickworks (ISBN 0-646-39234-4)

- Penrose, H (Ed)(1994) Brunswick: One History – Many Voices, Melbourne: Victoria Press (ISBN 0-724184538)

- McDonald, M. (1992). Put Your Whole Self In. Ringwood: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-016818-4. – An account of a women's hydrotherapy group at the Brunswick Baths.