Democratic Unionist Party

Democratic Unionist Party | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | DUP |

| Leader | Gavin Robinson (interim) |

| Chairman | The Lord Morrow |

| Lords Leader | The Lord Dodds of Duncairn |

| Deputy Leader | Gavin Robinson |

| Commons Leader | Gavin Robinson (interim) |

| General Secretary | Michelle McIlveen |

| Founder | Ian Paisley |

| Founded | 30 September 1971 |

| Preceded by | Protestant Unionist Party |

| Headquarters | 91 Dundela Avenue Belfast BT4 3BU[1] |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Centre-right to right-wing |

| Colours | Red, white, blue Copper (customary) |

| House of Commons (NI seats) | 7 / 18 |

| House of Lords | 6 / 790 |

| NI Assembly | 25 / 90 |

| Local government in Northern Ireland[7] | 122 / 462 |

| Website | |

| mydup | |

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) is a unionist, loyalist, British nationalist[8][9] and national conservative political party in Northern Ireland. It was founded in 1971 during the Troubles by Ian Paisley, who led the party for the next 37 years. It is currently led by Gavin Robinson, who is stepping in as an interim after the resignation of Jeffrey Donaldson. It is the second largest party in the Northern Ireland Assembly, and is the fifth-largest party in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom. The party has been described as centre-right[10][11][12] to right-wing[13][14][15][5] and socially conservative,[16][17] being anti-abortion and opposing same-sex marriage. The DUP sees itself as defending Britishness and Ulster Protestant culture against Irish nationalism and republicanism. It is also Eurosceptic and supported Brexit.[18][19]

The DUP evolved from the Protestant Unionist Party and has historically strong links to the Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster, the church Paisley founded. During the Troubles, the DUP opposed sharing power with Irish nationalists or republicans as a means of resolving the conflict, and likewise rejected attempts to involve the Republic of Ireland in Northern Irish affairs. It campaigned against the Sunningdale Agreement of 1973, the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985, and the Good Friday Agreement of 1998. In the 1980s, the DUP was involved in setting up the loyalist paramilitary movements Third Force[20][21][22] and Ulster Resistance,[23] the latter of which helped smuggle a large shipment of weapons into Northern Ireland.[24]

For most of the DUP's history, the Ulster Unionist Party was the largest unionist party in Northern Ireland; however, by 2004, the DUP had overtaken the UUP in terms of seats in both the Northern Ireland Assembly and the UK House of Commons. In 2006, the DUP co-signed the St Andrews Agreement and the following year agreed to enter into power-sharing devolved government with Sinn Féin,[25] who agreed to support the Police Service, courts, and rule of law. Paisley became joint First Minister of Northern Ireland. However, the DUP's only Member of the European Parliament (MEP), Jim Allister,[26] and seven DUP councillors[27] left the party in protest, founding the Traditional Unionist Voice.[28] Paisley was succeeded as DUP leader and First Minister by Peter Robinson (2008–2015), then by Arlene Foster (2015–2021). After Foster was ousted, Edwin Poots briefly became leader and nominated Paul Givan as First Minister, but was himself forced to step down after three weeks. In June 2021, he was succeeded by Jeffrey Donaldson. In protest against the Northern Ireland Protocol, Givan resigned as First Minister in February 2022,[29] collapsing the Northern Ireland Executive. On 30 January 2024, Sir Jeffrey Donaldson announced that the DUP had agreed a deal with the UK government that resulted in power-sharing being restored.[30]

History[edit]

1970s[edit]

The Democratic Unionist Party evolved from the Protestant Unionist Party, which itself grew out of the Ulster Protestant Action movement. The DUP was founded on 30 September 1971 by Ian Paisley, leader of the Protestant Unionist Party, and Desmond Boal, formerly of the Ulster Unionist Party. Paisley, a well-known Protestant fundamentalist minister, was the founder and leader of the Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster. He would lead both the DUP and the Free Presbyterian Church for the next 37 years, and his party and church would be closely linked. When the DUP formed, Northern Ireland was in the midst of an ethnic-nationalist conflict known as the Troubles, which began in 1969 and would last for the next thirty years. The conflict began amid a campaign to end discrimination against the Catholic/Irish nationalist minority by the Protestant/unionist government and police force.[31][32] This protest campaign was opposed, often violently, by unionists who viewed it as an Irish republican front. Paisley had led the unionist opposition to the civil rights movement. The DUP were more hardline or loyalist than the UUP and its founding arguably stemmed from worries of the Ulster Protestant working class that the UUP was not paying them enough heed.[33]

The DUP opposed the Sunningdale Agreement of 1973. The Agreement was an attempt to resolve the conflict by setting up a new assembly and government for Northern Ireland in which unionists and Irish nationalists would share power. The Agreement also proposed the creation of a Council of Ireland, which would facilitate co-operation between the governments of Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. The DUP won eight seats in the 1973 election to the Assembly. Along with other anti-Agreement unionists, the DUP formed the United Ulster Unionist Council (UUUC) to oppose the Agreement. In the February 1974 UK election, the UUUC won 11 out of 12 Northern Ireland seats, while the pro-Agreement unionists failed to win any. On 15 May 1974, anti-Agreement unionists called a general strike aimed at bringing down the Agreement. The strike coordinating committee included DUP leader Paisley, the other UUUC leaders, and the leaders of the loyalist paramilitary groups. The strike lasted fourteen days and brought Northern Ireland to a standstill. Loyalist paramilitaries helped enforce the strike by blocking roads and intimidating workers.[34][35][36] On the third day of the strike, loyalists detonated four car bombs in Dublin and Monaghan, killing 33 civilians.[37] The strike led to the downfall of the Agreement on 28 May.

Following the downfall of the Agreement, in 1975 the British government set up a Constitutional Convention, an elected body of unionists and nationalists which would seek agreement on a political settlement for Northern Ireland. In the election to the convention, the UUUC (which included the DUP) won 53% of the vote. The UUUC opposed a power-sharing government and recommended only a return to majority rule (i.e. unionist rule). As this was unacceptable to nationalists, the convention was dissolved.[38]

The DUP opposed UK membership of the European Economic Community (EEC). In June 1979, in the first election to the European Parliament, Paisley won one of the three Northern Ireland seats. He topped the poll, with 29.8% of the first preference votes.[39] He retained that seat in every European election until 2004, when he was replaced by Jim Allister, who resigned from the DUP in 2007 while retaining his seat.[26]

1980s and 1990s[edit]

During 1981, the DUP opposed the then-ongoing talks between British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and Taoiseach Charles Haughey. That year, Paisley and other DUP members attempted to create a Protestant loyalist volunteer militia—called the (Ulster) Third Force—which would work alongside the police and army to fight the Irish Republican Army (IRA). They organized large rallies where men were photographed in military formation waving firearms certificates. Paisley declared: "This is a small token of the men who are placed to devastate any attempt by Margaret Thatcher and Charles Haughey to destroy the Union".[40] The DUP helped organize a loyalist 'Day of Action' on 23 November 1981, to pressure the British government to take a harder line against the IRA.[41] Paisley addressed a Third Force rally in Newtownards, where thousands of masked and uniformed men marched before him. He declared: "My men are ready to be recruited under the crown to destroy the vermin of the IRA. But if they refuse to recruit them, then we will have no other decision to make but to destroy the IRA ourselves!"[42] In December, Paisley claimed that the Third Force had 15,000–20,000 members. James Prior, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, replied that private armies would not be tolerated.[41]

The Anglo-Irish Agreement was signed by the British and Irish governments in November 1985, following months of talks between the two. The Agreement confirmed there would be no change in the status of Northern Ireland without the consent of a majority of its citizens, and proposed the creation of a new power-sharing government. It also gave the Irish government an advisory role on some matters in Northern Ireland. Both the DUP and UUP mounted a major protest campaign against the Agreement, dubbed "Ulster Says No". Both unionist parties resigned their seats in the British House of Commons, suspended district council meetings, and led a campaign of mass civil disobedience. There were strikes and mass protest rallies.[43]

On 23 June 1986, DUP politicians occupied the Stormont Parliament Building in protest at the Agreement, while 200 supporters protested outside and clashed with police.[43] The DUP politicians were forcibly removed by police the next day.[43] On 10 July, Paisley and deputy DUP leader Peter Robinson led 4,000 loyalist supporters in a protest in which they 'occupied' the town of Hillsborough. Hillsborough Castle is where the Agreement had been signed.[43] On 7 August, Robinson led hundreds of loyalist supporters in an invasion of the village of Clontibret, in the Republic of Ireland. The loyalists marched up and down the main street, vandalised property, and attacked two Irish police officers (Gardaí) before fleeing back over the border. Robinson was arrested and convicted for unlawful assembly.[44]

On 10 November 1986, a rally was held in which DUP politicians Paisley, Robinson and Ivan Foster announced the formation of the Ulster Resistance Movement (URM). This was a loyalist paramilitary group whose purpose was to "take direct action as and when required" to bring down the Agreement and defeat republicanism.[23] Recruitment rallies were held in towns across Northern Ireland and thousands were said to have joined.[23] The following year, the URM helped smuggle a large shipment of weapons into Northern Ireland, which were shared out between the URM, the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and the Ulster Defence Association (UDA). Most, but not all, of the weaponry was seized by police in 1988. In 1989, URM members attempted to trade Shorts' missile blueprints for weapons from the apartheid South African regime. Following these revelations, the DUP said that it had cut its links with the URM in 1987.[24]

In the mid-1980s, the Irish republican party Sinn Féin began to contest and win seats in local council elections. In response, the DUP fought elections under the slogan "Smash Sinn Féin" and vowed to exclude Sinn Féin councillors from all council business. Their 1985 manifesto said "The Sinn Féiners must be ostracised and isolated" at all local government bodies. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, DUP councillors attempted to exclude Sinn Féin councillors by ignoring them, boycotting their speeches, or drowning them out by making as much noise as possible – such as by heckling and banging tables.[45]

In early January 1994, the UDA released a document calling for the repartition of Ireland with the goal of making Northern Ireland wholly Protestant.[46] The plan was to be implemented should the British Army withdraw from Northern Ireland. The Irish Catholic/nationalist-majority areas would be handed over to the Republic, and those left in the rump state would be "expelled, nullified, or interned".[46] DUP press officer Sammy Wilson spoke positively of the document, calling it a "valuable return to reality" and lauded the UDA for "contemplating what needs to be done to maintain our separate Ulster identity".[46]

1998–2004[edit]

During the Northern Ireland peace process of the 1990s, the DUP was initially involved in the negotiations under former United States Senator George J. Mitchell that led to the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, but withdrew in protest when Sinn Féin, an Irish republican party with links to the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA), was allowed to participate while the IRA kept its weapons. The DUP opposed the Agreement in the Good Friday Agreement referendum, in which the Agreement was approved with 71.1% of the electorate in favour.

The DUP's opposition was based on a number of reasons, including:

- The early release of paramilitary prisoners

- The mechanism to allow Sinn Féin to hold government office despite ongoing IRA activity

- The lack of accountability of ministers in the Northern Ireland Executive

- The lack of accountability of the North/South Ministerial Council and North/South Implementation Bodies

The DUP contested the 1998 Northern Ireland Assembly election that resulted from the Good Friday Agreement, winning 20 seats, the third-highest of any party. It then took up two of the ten seats in the multi-party power-sharing Executive. While serving as ministers, they refused to sit at meetings of the Executive Committee in protest at Sinn Féin's participation.[citation needed] The Executive ultimately collapsed over an alleged IRA espionage ring at Stormont (see Stormontgate).

The Good Friday Agreement relied on the support of a majority of unionists and a majority of nationalists in order for it to operate.[citation needed] During the 2003 Northern Ireland Assembly election, the DUP argued for a "fair deal" that could command the support of both unionists and nationalists. After the results of this election the DUP argued that support was no longer present within unionism for the Good Friday Agreement. They went on to publish their proposals for devolution in Ireland entitled Devolution Now.[47] These proposals have been refined and re-stated in further policy documents including Moving on[48] and Facing Reality.[49]

In the 2003 Northern Ireland Assembly election, the DUP won 30 seats, the most of any party. In January 2004, it became the largest Northern Ireland party at Westminster, when MP Jeffrey Donaldson joined after defecting from the UUP. In December 2004, English MP Andrew Hunter took the DUP whip after earlier withdrawing from the Conservative Party, giving the party seven seats, in comparison to the UUP's five, Sinn Féin's four, and the Social Democratic and Labour Party's (SDLP) three.

2005–2007[edit]

In the 2005 UK general election, the party reinforced its position as the largest unionist party, winning nine seats, making it the fourth largest party in terms of seats in the British House of Commons behind Labour, the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats. In terms of votes, the DUP was the fourth largest party on the island of Ireland.

At the local government election of 2005, the DUP emerged as the largest party at local government level with 182 councillors across Northern Ireland's 26 district councils.[50] The DUP had a majority of the members on Castlereagh Borough Council, which had long been a DUP stronghold and was home to party leader Peter Robinson, also in Ballymena Borough Council, home to the party's founder Ian Paisley, and finally Ards Borough Council. As well as outright control on these councils, the DUP was also the largest party in eight other councils – Antrim Borough Council, Ballymoney Borough Council, Banbridge District Council, Belfast City Council, Carrickfergus Borough Council, Coleraine Borough Council, Craigavon Borough Council and Newtownabbey Borough Council.

On 11 April 2006, it was announced that three DUP members were to be elevated to the House of Lords: Maurice Morrow, Wallace Browne, the former Lord Mayor of Belfast, and Eileen Paisley, a vice-president of the DUP and wife of DUP Leader Ian Paisley. None, however, sit as DUP peers.

On 27 October 2006, the DUP issued a four-page letter in the Belfast Telegraph newspaper asking "Are the terms of Saint Andrew's a basis of moving forward to devolution?", with responses to be received to its party headquarters by 8 November. It was part of the party's policy of consultation with its electorate before entering a power-sharing government.[citation needed]

On 24 November 2006, Ian Paisley refused to nominate himself as First Minister of Northern Ireland designate. There was confusion between all parties whether he actually said that if Sinn Féin supported policing and the rule of law that he would nominate himself on 28 March 2007 after the Assembly elections on 7 March 2007. The Assembly meeting was brought to an abrupt end when the building had to be evacuated because of a security breach. Paisley later released a statement through the press office stating that he did in fact imply that if Sinn Féin supported policing and the rule of law, he would go into a power-sharing government with them. This was following a statement issued by 12 DUP MLAs stating that what Ian Paisley had said in the chamber could not be interpreted as a nomination.[51]

In February 2007, the DUP suggested that it would begin to impose fines up to £20,000 on members disobeying the party whip on crucial votes.[52] On 24 March 2007 the DUP party executive overwhelmingly endorsed a resolution put to them by the party officers that did not agree to an establishment of devolution and an executive in Northern Ireland by the Government's deadline of 26 March, but did agree to setting up an executive on 8 May 2007.[25]

On 27 March 2007, the party's sole Member of the European Parliament (MEP), Jim Allister, resigned from the party, in opposition to the decision to enter a power-sharing government with Sinn Féin. He retained his seat as an independent MEP as leader of his new hard-line anti-St Andrews Agreement splinter group that he formed with other disaffected members who had left the DUP over the issue, Traditional Unionist Voice, a seat which he retained until Diane Dodds won the seat back for the DUP in 2009. MP Gregory Campbell warned on 6 April 2007 that his party would be watching to see if benefits flow from its agreement to share power with Sinn Féin.[53]

Robinson leadership (2008–2015)[edit]

On 31 May 2008, the party's central Executive Committee met at the offices of Castlereagh Borough Council where Ian Paisley formally stepped down as party leader and Peter Robinson was ratified as the new leader, with Nigel Dodds as his deputy.

On 11 June 2008, the party supported the government's proposal to detain terrorist suspects for up to 42 days as part of the Counter-Terrorism Bill, leading The Independent newspaper to dub all of the party's nine MPs as part of "Brown's dirty dozen".[54] The Times reported that the party had been given "sweeteners for Northern Ireland" and "a peerage for the Rev Ian Paisley", amongst other offers, to secure the bill.[55]

Members of the DUP were lambasted by the press and voters, after MPs' expenses reports were leaked to the media. Several newspapers[who?] referred to the "Swish Family Robinson" after Peter Robinson, and his wife Iris, claimed £571,939.41 in expenses with a further £150,000 being paid to family members.[citation needed] Further embarrassment was caused to the party when its deputy leader, Nigel Dodds, had the highest expenses claims of any Northern Ireland MP, ranking 13th highest out of all UK MPs.[56] Details of all MPs' expenses claims since 2004 were published in July 2009 under the Freedom of Information Act 2000.

In January 2010, Peter Robinson was at the centre of a high-profile scandal relating to his 60-year-old MP/MLA wife Iris Robinson's infidelity with a 19-year-old man, and alleged serious financial irregularities associated with the scandal.[57]

In the 2010 general election, the party suffered a major upset when its leader, Peter Robinson, lost his Belfast East seat to Naomi Long of the APNI on a swing of 22.9%. However, the party maintained its position elsewhere, fighting off a challenge from the Ulster Conservatives and Unionists – New Force in Antrim South and Strangford and from Jim Allister's Traditional Unionist Voice in Antrim North.

The DUP were strongly criticised after the Red Sky scandal in which DUP ministers attempted to influence a decision at a meeting of the Northern Ireland Housing Executive. The decision related to an £8 million contract of east Belfast firm Red Sky. The Housing Executive cancelled Red Sky's contract after a BBC Spotlight investigation into the company, which was shown to be overcharging taxpayers. The DUP cited "sectarian bias" in relation to the decision.[58] The party suspended DUP councillor Jenny Palmer, who sat on the executive board, after she confessed that DUP special adviser Stephen Brimstone pressured her into changing her vote at the meeting.

In the 2015 general election, when the result was expected to be a hung parliament, the issue of DUP and the UK Independence Party forming a coalition government with the UK Conservative Party was considered by Nigel Farage (leader of UKIP).[59][60] The then Deputy Prime Minister and leader of the Liberal Democrats, Nick Clegg, warned against this "Blukip" coalition, with a spoof website highlighting imagined policies from this coalition – such as reinstating the death penalty, scrapping all benefits for under 25s and charging for hospital visits.[61] Additionally, issues were raised about the continued existence of the BBC (as the DUP, UKIP and Conservatives had made a number of statements criticising the institution)[62] and support for same-sex marriage.[63][64] However, in an interview with BBC Radio 5 Live deputy leader of the DUP Nigel Dodds told BBC Newsline that the DUP was "against discrimination based on religion ... or sexual orientation".[64]

On 10 September 2015, Peter Robinson stepped aside as First Minister and other DUP ministers, with the exception of Arlene Foster, resigned their portfolios.[65]

Foster leadership (2015–2021)[edit]

Arlene Foster became leader of the DUP on 17 December 2015, and served as First Minister of Northern Ireland from January 2016 to January 2017.

Two days before the UK Brexit referendum, held on 23 June 2016, the DUP paid £282,000 for a four-page glossy wrap-around to the free newspaper Metro, which is distributed in major towns and cities in the British mainland, but not Northern Ireland, advocating a 'Leave' vote.[66]

On 4 October 2016, First Minister Arlene Foster and DUP MPs held a champagne reception at the Conservative Party conference, marking what some have described as an "informal coalition" or an "understanding" between the two parties to account for the Conservatives' narrow majority in the House of Commons.[67][68] The relationship between the parties was formalised after the 2017 United Kingdom general election with the signing of the Conservative–DUP agreement.[69] In October 2017, the DUP held a similar reception at the Conservative Party conference, which was attended by leading Conservative figures including First Secretary of State Damian Green, Brexit Secretary David Davis, then-Chief Whip Gavin Williamson, and party chairman Patrick McLoughlin.[70] This was reciprocated in November, when Damian Green and Conservative Chief Whip Julian Smith attended the DUP's conference, with Smith giving a keynote address.[71] The third such annual DUP reception at the Conservative conference took place in October 2018,[72] with Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond and former Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson addressing the DUP conference a month later.[73] Prominent Conservative MPs such as Environment Secretary Michael Gove, Leader of the House of Commons Andrea Leadsom, Defence Secretary Gavin Williamson, former International Development Secretary Priti Patel, Sports Minister Tracey Crouch, Defence Select Committee chair Julian Lewis, and European Research Group chair Jacob Rees-Mogg headlined various fundraising events for the DUP from 2017 onwards.[74][75]

Former UK Independence Party leader Nigel Farage also spoke at a DUP fundraiser in May 2018, with his main financial backer, Arron Banks, stating that he would support a bid by Farage to seek office as a DUP candidate after the end of his tenure as Member of the European Parliament in 2019.[76]

In her capacity as Minister of Enterprise, Trade and Investment in 2012, Foster oversaw the establishment of a green energy scheme, which led to the Renewable Heat Incentive scandal (RHI scandal). The scheme gave a perverse incentive to use more energy and increase their carbon footprint to those who signed up to it since they could claim £1.60 for every £1 spent on heating with, for example, wood pellets.[77] With no cost controls, it could cost the public purse up to £490 million.

Foster refused calls to step down as First Minister over her alleged role in the RHI scandal. In January 2017 this led Martin McGuinness to resign in protest and the Northern Ireland Executive collapsed. A snap election followed after Sinn Féin refused to re-nominate a deputy First Minister. In this Northern Ireland Assembly election, held in March 2017, the DUP lost 10 seats, leaving them only one seat and 1,200 votes ahead of Sinn Féin, a result described by the Belfast Telegraph as "catastrophic".[78] The withdrawal of the party whip from Jim Wells in May 2018 left the DUP on 27 seats, the same number as Sinn Féin.[79]

In the 2017 UK general election, the DUP had 10 seats overall, 3 seats ahead of Sinn Féin.[80] With no party having received an outright majority in the UK Parliament, the DUP entered into an agreement to support government by the Conservative Party.[81] A DUP source said: "The alternative is intolerable. For as long as Corbyn leads Labour, we will ensure there’s a Tory PM."[81] The DUP would later withdraw their support over new Prime Minister Boris Johnson's revised proposal for a deal with the EU.[82]

At the 2019 UK general election, the DUP lost vote share and lost two of its seats.[83]

Due to the RHI scandal and deadlock between the DUP and Sinn Féin, Northern Ireland did not have an Executive and the Assembly did not meet for three years. In January 2020, the main parties signed the New Decade, New Approach agreement and the Executive was re-formed with Foster as First Minister and Michelle O'Neill of Sinn Féin as deputy First Minister.

In April 2021, it was reported that the majority of DUP MLAs and MPs had signed a letter of no confidence in Foster. She therefore announced that she would step down as DUP leader in May and as First Minister in June.[84]

Poots leadership (2021)[edit]

After Foster's announcement, the DUP held its first ever leadership election in May 2021, with Edwin Poots becoming leader after narrowly defeating Jeffrey Donaldson.[85] This caused a fracture in the party. Some DUP members spoke of their "disgust" at the way in which Foster had been ousted. There were claims that Poots supporters engaged in bullying and intimidation during the leadership election, and some party members walked out before his speech.[85][86] Police also investigated claims the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) threatened members of Donaldson's campaign team.[87] Poots admitted party members were "bruised" but denied claims of intimidation. Several party members resigned, including councillors.[86][88]

On 17 June 21 days after becoming DUP leader, Poots announced he would be resigning after an internal party revolt. He said he would stay in post until a successor was elected.[89] He had agreed a deal whereby his close ally, Paul Givan, would become First Minister. In return, he would let Westminster pass Irish language law for Northern Ireland, which the DUP had earlier agreed to implement by signing the New Decade, New Approach agreement. Most DUP MLAs opposed Poots's decision, forcing him to step down.[90][91]

On 22 June, Jeffrey Donaldson was confirmed to be succeeding Poots, as the only candidate in the leadership contest.[92]

Donaldson leadership (2021–2024)[edit]

Jeffrey Donaldson was ratified as DUP leader on 30 June 2021, and said his top priority was to get rid of the Northern Ireland Protocol, the post-Brexit trade arrangements.[93] Hours after he became leader, MLA Alex Easton left the DUP, saying the party no longer had any "respect, discipline or decency".[94] This meant the DUP were no longer the biggest party in the Assembly.

As part of the party's protest against the Northern Ireland Protocol, the DUP's Paul Givan resigned as First Minister in February 2022, collapsing the Northern Ireland Executive.[95]

In April, shortly before the 2022 Assembly election, all of the DUP's officers in South Down refused to endorse the party's candidate Diane Forsythe and resigned from the DUP.[96]

In the May 2022 Assembly election, the DUP's vote share dropped almost 7% and it lost three seats, making Sinn Féin the largest party for the first time.[97] However, the DUP said they will not allow the election of a Speaker until their issues with the Northern Ireland Protocol are dealt with; meaning the Assembly cannot continue its business and a new Executive cannot be formed. The DUP were condemned by other parties for their actions.[98]

In July 2022, the DUP voted to support Prime Minister Boris Johnson in a confidence vote, making it the only party besides the Conservative Party to do so.[99]

Since the May 2022 election, the DUP has blocked the formation of a new Northern Ireland Assembly and Executive.[100]

Following the publication of the Windsor Framework, the DUP signalled opposition to the agreement.[101] The party formed a panel to form a report on the plan, members included; Arlene Foster, Peter Robinson, Carla Lockhart, Lord Weir, Ross Reed, John McBurney, Brian Kingston and Deborah Erskine.[102] David Kerr, the former UUP adviser to former First Minister David Trimble, has warned that DUP leadership risks splitting the party over its continued opposition to power sharing.[103]

In the 2023 Northern Ireland local elections, the DUP was overtaken by the Sinn Fein as the largest party. While the DUP maintained its 122 seats, the Sinn Fein was able to win 39 new seats to jump to 144 seats. After the election, Chris Heaton-Harris called for the party to end the boycott of Sinn Féin and work alongside the party.[104]

During Donaldson's leadership, the DUP has developed a 5 point plan "to build a better Northern Ireland within the Union", this includes "supporting and boosting [the] National Health Service, growing [the] economy and creating jobs, tackling the cost of living crisis, securing a better education system and negotiating the removal of the Irish Sea Border."[105]

On 29 January 2024, an urgent meeting of the DUP executive was called following the passing over the deadline to restore power sharing at Stormont.[106] Details of the meeting were reportedly leaked to the BBC.[107] Jeffrey Donaldson revealed in the morning that his party would return to Stormont.[108] The Northern Ireland Executive formation ended 23 months of stalemate.[109]

Donaldson resigned as leader on 29 March 2024 after being charged with historical sex offences.[110] Gavin Robinson was named as interim leader.[111][112]

Policies and views[edit]

Unionism[edit]

The Democratic Unionist Party are Ulster unionists, which means that they support Northern Ireland remaining part of the United Kingdom and are opposed to a united Ireland. The party sees itself as defending Britishness and Ulster Protestant culture against Irish nationalism and republicanism.[113][114] It supports marching rights for the loyalist Orange Order, which many DUP members are members of;[115] it is also in favour of flying the British Union Flag from government buildings all year round. The DUP assert that "Irish and Gaelic culture should not be allowed to dominate funding" in Northern Ireland[116] and have blocked proposed laws that would promote and protect the Irish language.[117][118] The DUP are staunch supporters of the British security forces and their role in the Northern Ireland conflict. The party wants to prevent British soldiers and police officers from being prosecuted for killings committed during the conflict.[119]

Ulster loyalism[edit]

The party has also been described as right-wing populist[5] and containing some extremist tendencies.[120][121] It is linked to the Ulster loyalist faction of unionism, which has been identified as a form of ethnic nationalism.[122] The DUP was endorsed in the 2017 general election by the Loyalist Communities Council, an umbrella group of loyalist paramilitary groups, which are proscribed terrorist organisations.[123] However, the party leadership strongly rejected the endorsement,[124][125] with party leader Arlene Foster stating: "We did not seek that statement, we did not seek endorsement from any paramilitary organisation and indeed I fundamentally reject an endorsement from anyone that's involved with paramilitarism or criminality."[126]

Euroscepticism and foreign policy[edit]

The DUP is a Eurosceptic party that supported the UK's withdrawal from the European Union in the 2016 Brexit referendum and was the only party in the Stormont power executive to campaign for leave.[127] The party opposes a hard Irish border,[128][129] and wishes to maintain the Common Travel Area.[130]

Speaking as a member of the European Parliament in 1991, then leader Ian Paisley set out the DUP's Eurosceptic position:

I wish to have no part whatsoever in the rebuilding of this Tower of Babel. God Almighty cursed and confounded that tower very long ago and no sensible person wants to make bricks without straw to rebuild such a monstrosity. I believe there is a way forward for Europe. The true future of the nations of Europe lies in co-operation and not in incorporation; in unity, but not in uniformity; in national sovereignty, not in international submergence, and in a family of nations, not in a federation of nations.[131]

Later in 1991, speaking at the DUP annual conference Paisley compared Chancellor of Germany Helmut Kohl to Kaiser Wilhelm II and Adolf Hitler.[131]

East Antrim MP Sammy Wilson caused controversy in March 2016 during a BBC Spotlight episode discussing the implications of the EU referendum, when he was recorded agreeing with a member of the public who said that they wanted to leave the European Union and "get the ethnics out". Wilson stated "You are absolutely right". Wilson said he was agreeing with the desire to leave the European Union, not the "ethnics out" call. Wilson was criticised by the Polish consul in Northern Ireland and various other political parties.[132]

The DUP strongly opposed the Northern Ireland backstop in 2019[133] seeing it as weakening Northern Ireland's place within the United Kingdom,[134] and this opposition was regarded by a number of commentators as the main reason why the withdrawal agreement was not ratified by the Parliament of the United Kingdom before 2020.[135][136][137] During most of the May government, the DUP said the Northern Ireland backstop must be removed from the Brexit withdrawal agreement for continued support of Theresa May's government in the House of Commons through the confidence and supply deal,[138][139] although the party said that it was open to a time limit on the backstop.[140]

The DUP voted "No" in all three meaningful votes on the EU Withdrawal Agreement negotiated by Theresa May.[141]

The DUP are strongly supportive of Israel.[142]

In 2011, the DUP abstained on military intervention in Libya.[143] The DUP opposed the British government's proposed military intervention against Bashar al-Assad in the Syrian Civil War in 2013.[144] However, the DUP supported military action against Islamic State targets in Syria in 2015.[145]

LGBT rights[edit]

The DUP is socially conservative and has strong links to the Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster, the small church founded by the party's founder Ian Paisley. The vast majority of DUP members are evangelical Christians and, on average, 65% of its representatives since the party was founded have been Free Presbyterians.[146] The party also has links with the Caleb Foundation, a Protestant fundamentalist pressure group.[147]

The DUP has opposed LGBT rights in Northern Ireland. Party leaders—as well as many prominent party members—have condemned homosexuality, and a 2014 survey found that two-thirds of party members believe homosexuality is wrong.[148]

Opposition to LGBT rights legislation[edit]

The DUP campaigned against the legalisation of homosexual acts, which it believed to be a "harmful deviance" linked to paedophilia, in Northern Ireland through the "Save Ulster from Sodomy" campaign between 1977 and 1982.[149]

The Labour government elected in 1997 sought to reform the law to extend LGBT rights. The DUP consistently voted against the Labour government, including by voting against reducing of the age of consent for gay sex from 18 to 16 in June 1998[150] (and again in February 2000[151]), against a motion for a gender-neutral Civil Registration Bill in October 2001,[152] against allowing unmarried gay and straight couples to adopt children in November 2002,[153] against the Gender Recognition Bill 2004,[154][155] against the Civil Partnership Act 2004,[156] for an amendment opposing the Equality Act (Sexual Orientation) Regulations 2007,[157] and against same-sex female couples and single mothers accessing in vitro fertilisation in January 2008.[158]

The party vetoed the legalisation of same-sex marriage in Northern Ireland from 2015 onwards, which for a time made Northern Ireland the only region of the UK where same-sex marriage was not permitted,[159] prior to the passage of the Northern Ireland (Executive Formation etc) Act 2019.[160][161] Former DUP minister Jim Wells called the issue a "red line" for power-sharing talks, adding that "Peter will not marry Paul in Northern Ireland".[162] In August 2012, in the wake of a council debate on same-sex marriage, Magherafelt DUP councillor Paul McClean called for homosexuality to be made illegal again in Northern Ireland. In response, the DUP reiterated their support for the "current definition of marriage", but did not comment with regard to outlawing homosexuality.[163] McClean repeated his comments in April 2015,[164] and a few days later, DUP leader Peter Robinson said that McClean was "entitled to that opinion", and that if homosexuality was illegal, he would "hope that people would obey the law".[165]

The party attempted to introduce a "conscience clause" into law in Northern Ireland, which would let businesses refuse to provide a service if it went against their religious beliefs. This came after a Christian-owned bakery was taken to court for refusing to make a cake bearing a pro-gay marriage slogan. Opponents argued that the clause would allow discrimination against LGBT people.[166]

Homosexuality 'cure' and conversion therapy controversies[edit]

In June 2008, Iris Robinson, commenting on a homophobic assault, offered to refer homosexuals to psychiatric counselling, suggesting it could "cure" him of his homosexuality. Although she condemned the attack, she called homosexuality an "abomination" that made her feel "sick" and "nauseous". In July, Robinson stated in Parliament that homosexuality was "viler" than child sex abuse, adding she felt "totally repulsed by both".[167] In a subsequent statement that same day, however, she said that she had "clearly intended to say that child abuse was even worse than homosexuality and sodomy". Her remarks were widely condemned by other parties and by the Northern Ireland Gay Rights Association,[167] with SDLP MP Alasdair McDonnell saying her comments "create space for all sorts of homophobic attacks".[168]

In November 2015, the DUP deputy mayor of Derry and Strabane, Thomas Kerrigan, suggested that homosexuality could be "cured" through prayer, suggesting that young people not attending church left themselves open to lifestyles such as "being gay", drinking, or taking drugs. Kerrigan's remarks attracted condemnation from the Rainbow Project and from Bebe Johnston, the mother of a gay man from Derry who died by suicide. While the DUP indicated Kerrigan's remarks were not party policy, they stated "party members may hold personal views on this matter".[169]

Internal dissent on LGBT issues[edit]

In recent years, the party has become more split on the issue of LGBT rights with some DUP members moderating their opinions on the matter. In 2021, The Guardian claimed that Arlene Foster softening her stance on LGBT issues was a contributing factor in her resignation as leader.[170][171] In July 2021, deputy leader Paula Bradley expressed an apology for the "absolutely atrocious" statements made by the party's politicians about LGBT people and added "there have been some very hurtful comments and some language that really should not have been used.”.[172] Her apology was supported by DUP leader Jeffrey Donaldson.[173] In September 2021, Donaldson met with the Rainbow Project, the first official meeting between a DUP leader and an LGBT group.[174]

However, the efforts of leading DUP figures to moderate the party's position has faced resistance. In 2019, following the selection of Alison Bennington, the DUP's first openly LGBT candidate (who would later be elected as a councillor), Ballymoney DUP alderman John Finlay issued a complaint to DUP party officers, stating his "deep concern" at "the decision to select an openly gay candidate", remarking that "Dr. Paisley must be turning in his grave".[175]

Abortion[edit]

Party members have campaigned strongly against any extension of abortion rights to Northern Ireland, unanimously opposing a bill by Labour MP Diana Johnson to protect women in England and Wales from criminal prosecution if they ended a pregnancy using pills bought online.[130][176] They have opposed extra funding for international family planning programmes.[176]

Economic and fiscal policies[edit]

The DUP is in favour of keeping the "triple lock" for pensions,[129] the Winter Fuel Allowance,[130] and greater spending in Northern Ireland for services such as health.[177]

The DUP revived calls for a 25-mile sea bridge to link Northern Ireland with Scotland.[citation needed]

To address the cost of living crisis, in the May 2022 Assembly Election the DUP supported a windfall tax on energy firms, and an energy support payment "to support hard-pressed families."[178]

The party has been described as "a right-wing party in terms of social issues, but left-of-centre on economic issues."[179]

Social policy[edit]

Some DUP politicians have called for creationism to be taught in state schools,[180][181] and for museums to include creationism in their exhibits.[182][183] In 2007, a DUP spokesman confirmed that these views were in line with party policy.[180]

In 2011, the DUP called for a debate in the House of Commons over bringing back the death penalty for some serious crimes such as murder or rape.[184]

Associations with loyalist paramilitaries[edit]

Though the party has never had official links to any major paramilitary organisation in Northern Ireland, multiple DUP members have had associations with loyalist groups, or expressed support for their actions, particularly during the Troubles. In 1972, William McCrea issued a press statement, saying, "We call on all Loyalists to give their continued support to the Ulster Defence Association as it seeks to ensure the safety of all law-abiding citizens against the bombs and bullets of the IRA. As the Catholic population have given their support to the IRA throughout this campaign of terror so must Loyalists grant unswerving support to those engaged in the cause of truth."[185] McCrea became the DUP party chairman in February 1976.[186] He and fellow DUP member Ivan Foster conducted funerals for Wesley Somerville and Harris Boyle, two UVF members who were killed while carrying out the Miami Showband killings in 1975.[187] Foster had given the graveside oration for Sinclair Johnston, a UVF member who was shot by police during rioting in Larne in 1972.[188]

McCrea also conducted the funeral service for Benjamin Redfern, a UDA member who was crushed while trying to escape the Maze Prison in a bin lorry in 1984. Redfern was serving a life sentence for the murder of two Catholics.[188] In 1996, Billy Wright, a former UVF member who had founded the breakaway Loyalist Volunteer Force, organised a rally in defence of 'free speech'. McCrea accepted an invitation to address the meeting.[185]

Omagh businessman Eddie Sayers stood as a DUP candidate in the 1973 Northern Ireland Assembly election for the constituency of Mid Ulster, but was not elected. He later became active in the UDA, and was appointed Brigadier for its Mid Ulster Brigade.[189]

Bangor DUP councillor Billy Baxter was arrested in 1993 and convicted for soliciting funds for the UVF. He was subsequently expelled from the party.[189]

In July 1994, DUP press officer Sammy Wilson and DUP deputy leader Peter Robinson were pallbearers at the funeral of UDA member Ray Smallwoods, who served half of a 15-year sentence for the attempted murder of Bernadette McAliskey in 1981.[190] That same year, the UDA drafted a document – the ‘Doomsday scenario’ – which declared that in the event of a British withdrawal from Northern Ireland, the organisation's aim would be to "establish an ethnic Protestant homeland" within which the Catholic population would be "expelled, nullified or interned." Wilson praised the document, describing it as a "very valuable return to reality" which "shows that some loyalist paramilitaries are looking ahead and contemplating what needs to be done to maintain our separate Ulster identity".[46]

Former DUP member Jim Allister represented loyalist Clifford McKeown in court in 2003.[191] McKeown, who was already serving 12 years for gun possession, was ultimately found guilty of the murder of Catholic taxi driver Michael McGoldrick in 1996, said to have been done as a "birthday present" for Billy Wright.[191] Allister said that McKeown would be appealing against the conviction.[191] Allister rejoined the DUP in 2004, and served as an MEP for the party from 2004 to 2007, before leaving to form the Traditional Unionist Voice, a party opposed to the St Andrews Agreement of 2006.

In 2006, George Seawright was listed by the UVF as one of its members killed during the Troubles.[192] Seawright was elected a DUP Belfast City Councillor in 1981, and a DUP candidate in the 1982 Northern Ireland Assembly election, though he was expelled from the party in 1984. His election agent was UVF leader John Bingham.[193]

Former UVF member John Smyth, who was jailed for his activities in the 1970s, was a DUP councillor on the Antrim Borough Council for over a decade.[194]

In 2014, Billy Hutchinson, a former member of the UVF who was convicted of murder in 1974, said that "most UVF men are DUP supporters, or those who vote anyway".[195]

In January 2023, DUP councillor and former Mayor of Lisburn Paul Porter took part in a march to mark the 25th anniversary of the shooting dead of UDA member Jim Guiney by the INLA. The march was criticised by Marian Walsh, whose 17-year-old son Damien was murdered by the UDA in 1993.[196]

In 2023, Tyler Hoey was selected as a DUP candidate to contest the Mid and East Antrim Council elections. In 2020, Hoey 'liked' a Twitter post commemorating the Greysteel massacre, which stated, "On this day 27 years ago, An Ulster Freedom Fighters Active Service Unit from North Antrim-Londonderry Brigade 'Trick or Treated' its way into the republican Rising Sun bar in Greysteel in order to gain revenge for the Shankill Bombing. Spirit of '93".[197] Following this revelation, DUP leader Jeffrey Donaldson said that Hoey "deeply regrets some of the things that he said in the past" and that he is "entitled to a second chance."[198]

Leadership[edit]

Founder Ian Paisley led the party from its foundation in 1971 onwards, and retired as leader of the party in spring 2008.

Paisley was replaced by former deputy leader Peter Robinson on 31 May 2008, who in turn was replaced by Arlene Foster on 17 December 2015.

Foster announced in April 2021 that she would stand down as leader on 28 May 2021.[84] Edwin Poots won the subsequent leadership election (the first in the party's history), against Sir Jeffrey Donaldson, however he stepped down after just 20 days in office and was replaced as leader by Donaldson on 26 June 2021. Donaldson resigned with immeditate effect on 29 March 2024.[199]

Party leader[edit]

The following are the terms of office as party leader and as First Minister of Northern Ireland:

| Leader | Portrait | Period | Constituency | Years as First Minister |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ian Paisley |

|

30 September 1971 – 31 May 2008 | MP for Bannside[n 1] (1970–72) MP for North Antrim (1970–2010) MEP for Northern Ireland (1979–2004) MLA for North Antrim (1998–2011) |

2007–2008 (Executive of the 3rd Assembly) |

| Peter Robinson |

|

31 May 2008 – 17 December 2015 | MP for Belfast East (1979–2010) MLA for Belfast East (1998–2016) |

2008–2011–2016 (Executive of the 3rd and 4th Assembly) |

| Arlene Foster |

|

17 December 2015 – 28 May 2021 | MLA for Fermanagh and South Tyrone (2003–2021) | 2016–2017, 2020–2021 (Executive of the 4th, 5th and 6th Assembly) |

| Edwin Poots |

|

28 May – 30 June 2021 | MLA for Lagan Valley (1998–2022) | N/A (Nominated Paul Givan)[200] |

| Jeffrey Donaldson |

|

30 June 2021 – 29 March 2024 | MP for Lagan Valley (1997–present) | N/A (Paul Givan remained as First Minister but later resigned; Emma Little-Pengelly later became deputy First Minister in Feb 2024)[201] |

| Gavin Robinson (interim) |

|

29 March 2024 – present | MP for Belfast East (2015–present) | N/A (serving ad interim until the election of a permanent leader) |

Deputy leader[edit]

| Name | Period | Constituency |

|---|---|---|

| William Beattie | 30 September 1971 – 31 May 1980 | MP for South Antrim (1970–72) |

| Peter Robinson | 31 May 1980 – 31 May 2008 | MP for Belfast East (1979–2010) MLA for Belfast East (1998–2016) |

| Nigel Dodds | 31 May 2008 – 28 May 2021 | MLA for Belfast North (1998–2010) MP for Belfast North (2001–2019) |

| Paula Bradley | 28 May 2021 – 9 June 2023 | MLA for Belfast North (2011–2022) |

| Gavin Robinson | 9 June 2023 – present | MP for Belfast East (2015–present) |

Chairman[edit]

| Period | Name |

|---|---|

| 1971–1973 | Desmond Boal |

| 1973–1980 | William Beattie |

| 1981–2000 | James McClure |

| 2000–present | Maurice Morrow |

General Secretary[edit]

| Period | Name |

|---|---|

| 1975–1979 | Peter Robinson |

| 1980–1983 | William Beattie |

| 1983–1992 | Alan Kane |

| 1993–2008 | Nigel Dodds |

| 2008–present | Michelle McIlveen |

Northern Ireland Executive Ministers[edit]

| Portfolio | Name |

|---|---|

| Deputy First Minister | Emma Little-Pengelly |

| Junior Minister (nominated by Deputy First Minister) | Pam Cameron |

| Minister for Communities | Gordon Lyons |

| Minister of Education | Paul Givan |

Westminster[edit]

- Party leaders at Westminster

| Name | Period | Constituency |

|---|---|---|

| Ian Paisley | 1974–2008 | North Antrim |

| Peter Robinson | 2008–2010 | Belfast East |

| Nigel Dodds | 2010–2019 | Belfast North |

| Jeffrey Donaldson | 2019–2024 | Lagan Valley |

| Gavin Robinson | 2024–present | Belfast East |

- Party Chief Whip at Westminster

| Name | Period | Constituency |

|---|---|---|

| Jeffrey Donaldson | 2015–2019 | Lagan Valley |

| Sammy Wilson | 2019–2024 | East Antrim |

- Party spokespersons at Westminster[202]

| Responsibility | Spokesperson |

|---|---|

| Leader of the DUP and Spokesperson for Northern Ireland | Jeffrey Donaldson |

| Leader of the DUP in the House of Lords | Lord Dodds of Duncairn |

| Chief Whip and Business in the House of Commons | Sammy Wilson |

| Deputy Chief Whip Spokesperson for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities Spokesperson for Transport |

Ian Paisley Jr |

| Spokesperson for International Development Spokesperson for International Trade Spokesperson for Foreign Affairs |

Gregory Campbell |

| Spokesperson for the Economy Spokesperson for Work and Pensions Spokesperson for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy |

Paul Girvan |

| Spokesperson for Defence Spokesperson for Home Affairs Spokesperson for Justice |

Gavin Robinson |

| Spokesperson for Health and Social Care Spokesperson for Education Spokesperson for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs |

Jim Shannon |

| Spokesperson for Equality PPS to the Leader of the DUP |

Carla Lockhart |

Representatives[edit]

Parliament of the United Kingdom[edit]

Members of the House of Commons following 12 December 2019 general election:

Members of the House of Lords

- The Lord Browne of Belmont

- The Lord Hay of Ballyore

- The Lord Morrow

- The Lord McCrea of Magherafelt and Cookstown

- The Lord Dodds of Duncairn

- The Lord Weir of Ballyholme

Northern Ireland Assembly[edit]

Members of the Northern Ireland Assembly as of May 2022:

- Maurice Bradley – East Londonderry

- Phillip Brett – Belfast North

- David Brooks – Belfast East

- Keith Buchanan – Mid Ulster

- Thomas Buchanan – West Tyrone

- Jonathan Buckley – Upper Bann

- Joanne Bunting – Belfast East

- Pam Cameron – South Antrim

- Trevor Clarke – South Antrim

- Diane Dodds – Upper Bann

- Stephen Dunne – North Down

- Deborah Erskine – Fermanagh and South Tyrone

- Diane Forsythe – South Down

- Paul Frew – North Antrim

- Paul Givan – Lagan Valley

- Harry Harvey – Strangford

- David Hilditch – East Antrim

- William Irwin – Newry and Armagh

- Brian Kingston – Belfast North

- Emma Little-Pengelly – Lagan Valley

- Gordon Lyons – East Antrim

- Michelle McIlveen – Strangford

- Gary Middleton – Foyle

- Edwin Poots – Belfast South

- Alan Robinson – East Londonderry

Election results[edit]

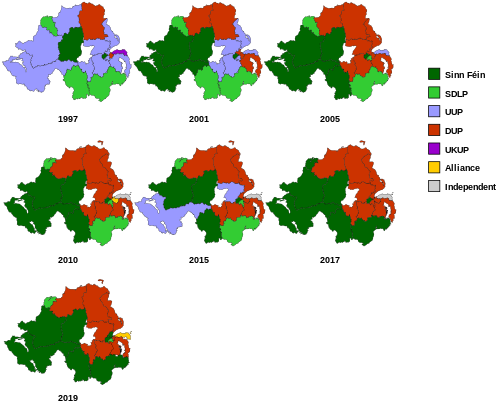

General election results[edit]

| Election | Leader | Share of votes | Seats | ± | Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feb 1974 | Ian Paisley | 5.7% | 1 / 12

|

Labour minority | |

| Oct 1974 | 5.8% | 1 / 12

|

Labour | ||

| 1979 | 10.2% | 3 / 12

|

Conservative | ||

| 1983 | 19.9% | 3 / 17

|

Conservative | ||

| 1987 | 11.7% | 3 / 17

|

Conservative | ||

| 1992 | 13.1% | 3 / 17

|

Conservative | ||

| 1997 | 13.6% | 2 / 18

|

Labour | ||

| 2001 | 22.5% | 5 / 18

|

Labour | ||

| 2005 | 33.7% | 9 / 18

|

Labour | ||

| 2010 | Peter Robinson | 25.0% | 8 / 18

|

Conservative-Liberal Democrats coalition | |

| 2015 | 25.7% | 8 / 18

|

Conservative | ||

| 2017 | Arlene Foster | 36.0% | 10 / 18

|

Conservative minority with DUP confidence & supply | |

| 2019 | 30.6% | 8 / 18

|

Conservative |

Northern Ireland Assembly election results[edit]

| Election | Northern Ireland Assembly | Leader | Total Votes | Share of votes | Seats | +/- | Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1973 | 1973 Assembly | Ian Paisley | 78,228 | 10.8% | 8 / 78

|

Opposition | |

| 1975 | Constitutional Convention | 97,073 | 14.8% | 12 / 78

|

Fourth largest party | ||

| 1982 | 1982 Assembly | 145,528 | 23.0% | 21 / 78

|

Opposition | ||

| 1996 | Forum | 141,413 | 18.8% | 24 / 110

|

Second largest party | ||

| 1998 | 1st Assembly | 145,917 | 18.5% | 20 / 108

|

Junior party in coalition | ||

| 2003 | 2nd Assembly | 177,944 | 25.7% | 30 / 108

|

Largest party, direct rule | ||

| 2007 | 3rd Assembly | 207,721 | 30.1% | 36 / 108

|

Coalition | ||

| 2011 | 4th Assembly | Peter Robinson | 198,436 | 30.0% | 38 / 108

|

Coalition | |

| 2016 | 5th Assembly | Arlene Foster | 202,567 | 29.2% | 38 / 108

|

Coalition | |

| 2017 | 6th Assembly | 225,413 | 28.1% | 28 / 90

|

Coalition | ||

| 2022 | 7th Assembly | Jeffrey Donaldson | 184,002 | 21.3% | 25 / 90

|

Junior party in coalition |

See also[edit]

- List of Democratic Unionist Party MPs

- List of Northern Ireland Members of the House of Lords

- British Isles fixed sea link connections

- Democratic Unionist Party scandals

Notes[edit]

- ^ (Northern Ireland Parliament).

References[edit]

- ^ "The Electoral Commission – Democratic Unionist Party – D.U.P." Archived from the original on 20 August 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ a b c Nordsieck, Wolfram (2017). "Northern Ireland/UK". Parties and Elections in Europe. Archived from the original on 7 November 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ "Unionist bid to be UK 'kingmakers' unsettles some in Northern Ireland". Reuters. Archived from the original on 12 July 2015. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ Smithey, Lee. Unionists, Loyalists, and Conflict Transformation in Northern Ireland. Oxford University Press, 2011. pp.56, 58

- ^ a b c Ingle, Stephen (2008). The British Party System: An Introduction. Routledge. p. 156.

- ^ DUP to recommend leaving EU to voters Archived 23 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine. BBC NEWS. Published 20 February 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "NI council elections 2023: Sinn Féin largest party in NI local government". BBC. 21 May 2023. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ Smithey, Lee. Unionists, Loyalists, and Conflict Transformation in Northern Ireland. Oxford University Press, 2011. pp.56, 58

- ^ McAuley, James. Very British Rebels?: The Culture and Politics of Ulster Loyalism. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015. p.140

- ^ Devenport, Mark (9 June 2017). "Could the DUP be Westminster kingmakers?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 4 May 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "Everything you need to know about the DUP, the party supporting the new Tory government". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 2 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ Anttiroiko, Ari-Veikko; Mälkiä, Matti (2007). Encyclopedia of Digital Government. Idea Group Inc (IGI). p. 394. ISBN 978-1-59140-790-4. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "It will be ‘difficult’ for May to survive, says N Ireland’s DUP" Archived 16 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine, By Vincent Boland & Robert Wright. Financial Times. 9 June 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2017

- ^ "Who Are The DUP? The Democratic Unionist Party Explained" Archived 11 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine, LBC. 9 June 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ Peck, Tom (10 June 2017). "Theresa May to enter into 'confidence and supply' arrangement with the Democratic Unionists". The Independent. Archived from the original on 11 June 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ "General election 2017: Tories and DUP 'still in discussions'". BBC News. 11 June 2017. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ Marcus, Ruth (14 January 2010). "Ruth Marcus – Gender aside, the fall of Irish politician Iris Robinson is the same old sex scandal". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ "DUP confirms it will campaign for Brexit in Leave/Remain referendum". Belfast Telegraph. 20 February 2016. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

The Democratic Unionist Party has formally announced its intention to campaign for a Brexit.

- ^ Jamie Merrill (9 June 2017). "What is the DUP position on Brexit?". The Essential Daily Briefing. iNews. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

No-one wants to see a 'hard' Brexit, what we want to see is a workable plan to leave the European Union, and that's what the national vote was about – therefore we need to get on with that.

- ^ "Ian Paisley death: Third Force 'were a motley crew of teens and farmers...'". Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- ^ Unionism and Orangeism in Northern Ireland Since 1945. Belfast: Blackstaff Press. p. 199.

The men on the Antrim hillside became the nucleus of a paramilitary formation 'The Third Force' which would play a role in what the DUP called 'The Carson Trail'

- ^ Wood, Ian S. (2006). Crimes of Loyalty: A History of the UDA. Edinburgh University Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0748624270.

Dr Ian Paisley, who had been close to Bradford, called for tax and rent strikes by Loyalists and announced the formation of a new paramilitary body for which he claimed he was helping to recruit. Because it was to supplement the RUC and UDR, he called it the 'Third Force'

- ^ a b c "Abstracts of Organisations: U". Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN). Archived from the original on 22 February 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ a b "A spectre from the past back to haunt peace" Archived 13 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Belfast Telegraph. 10 June 2007. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ a b "DUP 'would share power in May'". BBC News Online. BBC. 24 March 2007. Archived from the original on 28 March 2007. Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- ^ a b "Allister quits power-sharing DUP". BBC News Online. BBC. 27 March 2007. Archived from the original on 30 March 2007. Retrieved 27 March 2007.

- ^ "Seventh councillor leaves the DUP". BBC News Online. BBC. 5 April 2007. Archived from the original on 3 May 2007. Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- ^ "New unionist group to be launched". BBC News. Archived from the original on 9 December 2007. Retrieved 7 December 2007.

- ^ "Paul Givan resigns as NI First Minister". Raidió Teilifís Éireann. 3 February 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ "DUP agrees deal with UK government to restore power-sharing to Northern Ireland". Sky News. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ Richard English. The State: Historical and Political Dimensions, Charles Townshend, 1998, Routledge, p. 96; ISBN 0-41515-477-4.

- ^ Dominic Bryan. Orange Parades: The Politics of Ritual, Tradition and Control, Pluto Press (2000), p. 94; ISBN 0-74531-413-9.

- ^ "Beyond the Sectarian Divide: the Social Bases and Political Consequences of Nationalist and Unionist Party Competition in Ireland" by Geoffrey Evans and Mary Duffy. In British Journal of Political Science, Vol. 27, No. 1. (January 1997), p.58

- ^ David George Boyce and Alan O'Day. Defenders of the Union: a survey of British and Irish unionism since 1801. Routledge, 2001. p.255.

- ^ Tonge, Jonathan. Northern Ireland: Conflict and Change. Pearson Education, 2002. p.119.

- ^ "CAIN: Events: UWC Strike: Anderson, Don. – Chapter from '14 May Days'". Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ Oireachtas Sub-Committee report Archived 7 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine on the Barron Report (2004), p.25

- ^ Dr Martin Melaugh. "Northern Ireland Constitutional Convention – A Summary of Main Events". Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN). Archived from the original on 16 September 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ A Chronology of the Conflict – 1979 Archived 6 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN).

- ^ Henry Patterson, Eric P. Kaufmann. Unionism and Orangeism in Northern Ireland Since 1945. Manchester University Press, 2007. p.198-199

- ^ a b A Chronology of the Conflict – 1981 Archived 6 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN)

- ^ Hall, Michael. The Death of the Peace Process?: A survey of community perceptions. Island Publications, 1997. p.10

- ^ a b c d Anglo-Irish Agreement – Chronology of Events Archived 6 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN). Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ^ "A Chronology of the Conflict – 1986". Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN). Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ McAuley, James. The politics of identity: a loyalist community in Belfast. Avebury, 1994. p.77

- ^ a b c d Wood, Ian S. Crimes of Loyalty: A History of the UDA. Edinburgh University Press, 2006. Pages 184–185.

- ^ Martin Melaugh. "CAIN: Issues: Politics: Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) (2004) Devolution Now: The DUP's Concept for Devolution, 5 February 2004". Cain.ulst.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 13 May 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ Moving On, Democratic Unionist Party Archived 13 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Facing Reality, Democratic Unionist Party Archived 13 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "2005 Local Government Election Results". Northern Ireland Elections. ARK. Archived from the original on 9 August 2007. Retrieved 24 August 2007.

- ^ "Paisley 'will accept nomination'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 4 January 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ Sunday Times, page 1.10, 4 February 2007

- ^ Noel McAdam (6 April 2007). "Agreement must bring benefits, Congressmen are told". Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 6 April 2007.

- ^ "Twelve good folk and true... or Brown's dirty dozen?". The Independent. London. 15 June 2008. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ^ Sharrock, David; Coates, Sam (12 June 2008). "42 day detention: bribes and concessions that got DUP on side". The Times. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

Sweeteners for Northern Ireland and a peerage for the Rev Ian Paisley, dropping sanctions on Cuba and the governorship of Bermuda were among the offers the Government is thought to have used to secure Gordon Brown's victory in yesterday's vote.

- ^ "Dodds' expenses bill NI's highest". BBC News. Archived from the original on 4 January 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ O'Doherty, Malachi (8 January 2010). "The real Robinson affair". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 21 May 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ^ "The DUP's full role in Red Sky row revealed". The Detail. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- ^ Justice, Adam (18 March 2015). "General Election 2015: Ukip could form coalition with Tories and DUP". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ Wilkinson, Michael (5 May 2015). "Conservative Ukip coalition: what have the parties said". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ Cromie, Claire (16 April 2015). "Nick Clegg warns of rightwing 'Blukip' alliance of DUP, Ukip and the Conservatives". The Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ Stone, Jon (28 April 2015). "Tory coalition with DUP and Ukip could spell the end of the BBC as we know it". The Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ Dunne, Ciara (16 March 2015). "An alliance with the DUP will be a harder bargain than either Labour or the Tories think". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 8 April 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ a b Stroude, Will (5 May 2015). "Owen Jones warns of 'homophobic' DUP holding influence over future government". Attitude Magazine. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ "Statement by First Minister & DUP Leader Peter Robinson MLA". www.mydup.com. Archived from the original on 16 September 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ "What connects Brexit, the DUP, dark money and a Saudi prince?". The Irish Times. 16 May 2017. Archived from the original on 12 June 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ Manley, John (14 October 2016). "NI Conservatives' disquiet over DUP love-in to be raised with party HQ". The Irish News. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ Gibbon, Gary (4 October 2016). "Tories look to increase majority with DUP deal". Channel 4. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ "Conservatives agree pact with DUP to support May government". BBC News. 26 June 2017. Archived from the original on 26 June 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ "Tory-DUP deal is 'not temporary' says Nigel Dodds". BBC News. 4 October 2017. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ^ "Dublin accused of hijacking talks". The Times. 25 November 2017. Archived from the original on 25 November 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- ^ "Arlene Foster to address DUP reception at Tory conference". The Irish News. 2 October 2018. Archived from the original on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- ^ "Boris Johnson and Philip Hammond 'to attend DUP conference'". BBC. 20 November 2018. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- ^ "Top Tories speak at £1,500‑a‑table Unionist dinners". The Times. 10 March 2018. Archived from the original on 14 May 2018. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ "Jacob Rees-Mogg snubs Tories to appear at DUP fundraiser". Belfast Telegraph. 31 December 2018. Archived from the original on 31 December 2018. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- ^ "Nigel Farage's Ukip backer Arron Banks bolsters his DUP bid". The Times. 13 May 2018. Archived from the original on 16 May 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ "Q&A: What is the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) scheme?". BBC News. 13 December 2016. Archived from the original on 23 June 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ^ McAdam, Noel (7 March 2017). "I want one party for unionism, says DUP's Arlene Foster". Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ^ Cross, Gareth (10 May 2018). "It's a tie: DUP's Wells says removal of whip gives Sinn Fein equal voting power in Northern Ireland". Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ^ "Election results 2017: DUP and Sinn Féin celebrate election gains". BBC News. 9 June 2017. Archived from the original on 9 June 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ a b McDonald, Henry; Syal, Rajeecv (9 June 2017). "May reaches deal with DUP to form government after shock election result". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ "DUP says it cannot support Boris Johnson's Brexit deal". The Guardian. 17 October 2019. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ McClements, Freya (13 December 2019). "North returns more nationalist than unionist MPs for first time". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Arlene Foster announces resignation as DUP leader and NI first minister". BBC News. 28 April 2021. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ a b "DUP members ratify Edwin Poots as party leader" Archived 2 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News, 27 May 2021.

- ^ a b "DUP Stormont team: Little sign of healing, say outgoing ministers". BBC News. 8 June 2021. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ "Police investigating claims of UDA intimidation during DUP leadership contest" Archived 24 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine. The Irish News, 29 May 2021.

- ^ "'I felt I never fitted in': The inside story of two rising female stars' DUP departure". Belfast Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ "DUP leader Edwin Poots resigns amid internal party revolt" Archived 28 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News, 17 June 2021.

- ^ "Q&A: What went wrong for the DUP's shortest-serving leader?" Archived 28 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News, 18 June 2021.

- ^ Kearney, Vincent (20 June 2021). "The chaotic downfall of the DUP triumvirate". RTE. Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ Pogatchnik, Shawn (22 June 2021). "Jeffrey Donaldson to be crowned DUP leader unopposed". POLITICO. Archived from the original on 22 June 2021. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ "DUP leadership: Sir Jeffrey Donaldson ratified as party leader" Archived 1 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News, 30 June 2021.

- ^ "Alex Easton: DUP MLA quits hours after Donaldson ratified as leader" Archived 1 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News, 1 July 2021.

- ^ "DUP: NI First Minister Paul Givan announces resignation". BBC News. 3 February 2022.

- ^ "DUP officers in South Down, representing 305 years' party membership, dramatically resign". The News Letter. 26 April 2022.

- ^ "NI election results 2022: The assembly poll in maps and charts". BBC News. 8 May 2022. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "Northern Ireland Protocol: Assembly Speaker blocked by DUP for second time". BBC News. 30 May 2022.

- ^ "DUP only party outside Tories to support PM in no confidence vote". Belfast Telegraph. 19 July 2022.

- ^ "DUP will not drop block on Stormont Assembly sitting over organ donation law". The Independent. 13 February 2023.

- ^ "Brexit: DUP will vote against Windsor Framework plans". BBC News. 20 March 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ "DUP panel submits Windsor Framework report". BBC News. 31 March 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ "DUP leadership 'risks splitting party' over Windsor Framework". BBC News. 3 April 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ Carroll, Rory (21 May 2023). "DUP urged to restore power-sharing in Northern Ireland after Sinn Féin poll triumph". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ "Democratic Unionist Party | Northern Ireland". DUP. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

The DUP has a five-point plan to build a better Northern Ireland within the Union, by supporting and boosting our National Health Service, growing our economy and creating jobs, tackling the cost of living crisis, securing a better education system and negotiating the removal of the Irish Sea Border.

- ^ "DUP set for crunch meeting as party leader briefs members on proposals to end Stormont boycott". ITV Northern Ireland. 29 January 2024.

- ^ "DUP mole 'wore a wire' to leak meeting to Jamie Bryson". BBC News. 30 January 2024. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ "Leaks, tweets and cries of deceit - but a deal was done". BBC News. 30 January 2024. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ "DUP: Next days crucial for Stormont return, says Sinn Féin". BBC News. 30 January 2024. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ "DUP leader Sir Jeffrey Donaldson quits after sex offence charges". BBC News. 29 March 2024.

- ^ Kearney, Vincent (29 March 2024). "DUP leader Jeffrey Donaldson steps down after allegations". Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ Graham, Seánín (29 March 2024). "Jeffrey Donaldson resigns as leader of Democratic Unionist Party after being charged with historical allegations". The Irish Times. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ James W. McAuley, Graham Spencer. Ulster Loyalism After the Good Friday Agreement. Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. p. 124

- ^ "DUP fights back against 'erosion of Britishness'" Archived 2 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The News Letter. 25 June 2008.

- ^ Tonge, Jonathan. The Democratic Unionist Party: From Protest to Power. Oxford University Press, 2014. p. 151.

- ^ Muller, Janet. Language and Conflict in Northern Ireland and Canada: A Silent War. Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. p. 122.

- ^ "DUP will never agree to Irish language act, says Foster" Archived 11 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. 6 February 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ "The role of the Irish language in Northern Ireland’s deadlock" Archived 15 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Economist. 12 April 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ "DUP veterans motion prompts strong Commons support" Archived 10 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The News Letter. 23 February 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ McCulloch, Allison (2014). Power-Sharing and Political Stability in Deeply Divided Societies. Routledge. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-317-68219-6. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ McGarry, John; O'Leary, Brendan (17 June 2013). The Politics of Ethnic Conflict Regulation: Case Studies of Protracted Ethnic Conflicts. Routledge. p. 135. ISBN 9781136146527. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ Ignatieff, Michael. Blood and Belonging: Journeys into the New Nationalism. Vintage, 1994. p.184.

- ^ Manley, John (7 June 2017). "Arlene Foster urged to make unequivocal rejection of loyalist paramilitary support". The Irish News. Archived from the original on 13 June 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ Gordon, Gareth (7 June 2017). "DUP 'divorces' from Loyalist endorsement". BBC News. Archived from the original on 9 June 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ Young, David (7 June 2017). "Arlene Foster rejects paramilitary-linked backing for party". Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 7 June 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ "Foster: DUP 'fundamentally rejects' endorsement from paramilitary groups". News Letter. Archived from the original on 10 June 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ "From abortion to evolution: the terrifying views of the DUP you need to know". The Independent. 9 June 2017. Archived from the original on 12 June 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2017.