Talk:Tritone

| This is the talk page for discussing improvements to the Tritone article. This is not a forum for general discussion of the article's subject. |

Article policies

|

| Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

| This It is of interest to the following WikiProjects: |

|||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Alternatives[edit]

Where do we mention that the tritone is alo known as Diabolo in Musica, Diabolus in musica, or Diavolo in musica? Would improve findability. PS apologies for any newbie mistakes in editing Tacoekkel (talk) 16:35, 1 May 2008 (UTC)

I went ahead and threw that into the first paragraph. Gingermint (talk) 00:54, 30 September 2009 (UTC)

- I've added a link to Diabolo (disambiguation). Tayste (edits) 20:31, 5 December 2012 (UTC)

Examples[edit]

Need to mention use of the tritone in Don Giovanni.

- Feel free to do so by editing the article! (I can't add anything about this myself, because I didn't know the tritone was particularly significant in Don Giovanni.) --Camembert

- tritone is used a lot in West Side Story too -- Tarquin 14:58 17 May 2003 (UTC)

- Danse Macabre also uses the tritone, I believe that to achieve the correct opening effect (after the "clock" strikes thirteen) the soloist is required to detune his E string to E flat thus forming a tritone between the open A and E(flat) strings.

I think the opening notes of "The Simpsons" theme are a tritone (actually, something like C -> F#+G) and it is used heavily throughout the tune. njh 4 July 2005 00:09 (UTC)

- I knos that the simpsons theme song is in the dorian key. I don't think there are any intervals of a tritone however.207.157.121.50 11:17, 14 October 2005 (UTC)mightyafrowhitey.

- Tritone can also be built from the major third and a flatted seventh at the bass,using a second inversion progression at the right hand —Preceding unsigned comment added by 41.74.91.137 (talk) 10:40, 5 July 2010

- Actually it's in the Lydian mode.

- Note quite - it's in "Lydian dominant"! (lydian 7) Musical_mode#Other_types_of_modes

There were way too many examples, there are thousands and thousands of popular songs with this paticular interval in them and we don't need more than a handful. To point out some famous heavy metal songs or a single film soundtrack by a well known film composer use it is useful, that a paticular Primus or a Red Hot Chili Peppers song has it in is not. The Jimi Hendrix one is good though because that intro is nothing but the interval. 86.130.146.221 22:01, 9 January 2007 (UTC)

- "The tritone is used very extensively throughout Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 8 in C minor, "Pathétique"." Is this use more extensive than in other minor key works of the composer/period? Any references to published studies? Apus 11:38, 19 April 2007 (UTC)

Unfortunately little study has been done, to my knowledge, on the tritone. The AS Cambridge music course focuses on this interval quite significantly which may lead to students doing research in this area for their a2 investigation and report. I conducted my report on the Diminished 7th chord which is really a close relative of the tritone, but not solely on the tritone. Beethoven used it profusely in the Pathetique sonata. Every few bars you experience a tritone. Especially at the beginning and end.

What I find interesting about the tritone is how people were afraid of using it in the past due to its connections with satan. Does anyone have any examples of the tritone being used in baroque or earlier works? Many church hymns include tritones (For those in peril on the sea and such) but other than that, I have been unable to find many tritones being used deliberately in older music. An interesting field to look into.

Jake381 10:41, 30 May 2007 (UTC)

- Hi Jake! Are you sure that people were afraid of using it in the past on account of its connections with Satan? This seems to be a recent myth, as the article discusses, and not something supportable based on the documents of the time. It was not an often used interval because it was both large and dissonant (you won't find many melodic sevenths either), but I've never seen a demonic or Satanic connection before the 18th c. (when it's already in common use). There's a fourteenth century work about avoiding the tritone, but it's couched entirely in musical reasons, not religious or moral. -- Myke Cuthbert (talk) 16:24, 30 May 2007 (UTC)

- Greetings Mscuthbert! Though I would not place my life upon my statements as above, from my searchings I have come to my personal conclusion that it was used for this reason. I cannot see any reason otherwise why they would avoid this interval so determinedly. Dissonance creates interest in music. Before say Mozarts time I would hazrad to say that people were much more afraid of the powers that be. Though there will most likely be no written evidence that people avoided this interval, it did inherit the name "diabolus in musica". Surely nobody would wish to put the devil in their music without worrying about public reaction? Pre Classical composers still had patrons didn't they? Nice to converse with other musically aware! I don't get to much anymore :( Jake381 07:10, 7 June 2007 (UTC)

- Except that they didn't actually avoid it all that markedly. It's present even in Renaissance church music—in passing, like all dissonances (and this was a time when even major and minor thirds were considered dissonant). The term "diabolus in musica" doesn't appear in a religious context anywhere. It probably comes from the fact that they're really difficult to sing and stay in tune. — Gwalla | Talk 04:07, 29 February 2008 (UTC)

- I first heard the term "Diabolus In Musica" in the 1970s, when it was the focus of a 'Pied Piper' programme presented and written by David Munrow, an expert in and performer of mediaeval and Renaissance music. I wonder if the BBC still have a recording or transcript of that programme? I am a mathematician with a musical bent, and this inspiring programme certainly informed my understanding of music, and teaching of mathematics! Sasha (talk) 22:52, 28 November 2012 (UTC)

Abbreviation for Tritone[edit]

All the other articles about intervals mention an abbreviation, such as P5 or M2. i can't seem to recall what the abbreviation is for augmented and diminished intervals, and I was displeased not to find the answer here... Luqui 19:55, 31 December 2005 (UTC)

- a4 (or A4) or d5 are in common use. Frequently you will see them notated as x4 for the augmented 4th and ο5 for the dim 5th

Pi[edit]

Is it true that "a common symbol for tritone is π"? We used "TT" in school. Hyacinth 11:28, 23 February 2006 (UTC)

- I have never seen pi used, so I'm removing it until someone provides a source. —Keenan Pepper 13:59, 23 February 2006 (UTC)

- For goodness sake that's T.T (Tri Tone), which is commonly used, only someone wrote the two Ts too close together once and someone else interpreted it as a pi symbol.--JamesTheNumberless 15:52, 19 January 2007 (UTC)

- Did you mean T.T. (not T.T) with a period after each T? I never saw TT or T.T. used anywhere myself, and I personally don't like either of them, because each requires more than one character to represent an interval, which gets confusing when strung together. Also the real word is "tritone", not "tri tone", so the second "T" in TT or T.T. capitalizes a letter found in the middle of the word, in which case, to be consistent, semitone would have to be abbreviated "S.T.", but whatever, it doesn't matter what any of us happened to see in some class or happen to use ourselves or happen to like. What matters is what can be backed up by citation, of which there still is none for "TT" or "T.T.". By the way, Howard Hanson used "t" (the single, lower case character) to represent the tritone in his "Harmonic materials of modern music: resources of the tempered scale", which absolutely could be cited (here's a peek http://archive.org/stream/harmonicmaterial00hans#page/10/mode/2up/search/tritone), but his system is a little different in that octaves are ignored, and all intervals are reduced to their smallest inversion. For example, a major seventh interval equates to a half step, so his system doesn't really apply in this article. Still, "t" would be so much more convenient than "TT" or "T.T." would be. Whatever.—76.94.244.40 (talk) 21:50, 31 March 2013 (UTC)

- "As far as I know" is nice for the talk page (I'm guilty of it too), but it doesn't help the article. Can you cite the use of TT?—76.94.244.40 (talk) 01:14, 1 April 2013 (UTC)

April 08 edit[edit]

The tritone wasn't exploited after equal temperament (which doesn't really have a good date to speak of, anyway, if you leave it unqualified. 1600? 1920?). It really began to be exploited as a modulation in the Romantic period by composers like Chopin, Liszt, and Schumann (there are of course earlier examples, but they are less extensive). By the 20th century is was a natural part of the tonal language of composers like Holst, Vaughan Williams, and Rachmaninov. The reason it was used is for that "unexpected" quality of modulating to a key drastically unrelated to the previous. (How much of this should go in the article?)

Inverted at the octave, no interval except the tritone retains its identity. Why qualify it as the only one within the octave, when none without the octave do?

To say it has no "harmonic relationship" is false unless your definition of harmonic interval dictates that every equal tempered interval has no harmonic relationship. The ET-tritone has justifications; they are just more ambiguous than any other interval.

I've put the later points into a bulleted list, because they are more or less a random collection of facts about the tritone. Rainwarrior 19:30, 8 April 2006 (UTC)

- By "no harmonic relationship" I mean that because the ratio of 1 to the square root of 2 is mathematically irrational, two vibrating bodies tuned to a tritone that start in unision will NEVER return to unison, whereas when they are tuned to, say, an octave they will be passing the zero point in the same direction simultaneously (which is what I mean by "move in unison" in this context) after the slower has gone through one cycle and the faster through two. This follows from the mathematical nature of the root of 2. --Hugh7 08:20, 8 June 2006 (UTC)

- I don't quite understand what process you are describing. Two pitches at a tritone, which "start" in unison? Then they return to unison, while constantly moving in the same direction? Is the speed in this direction geometric or arithmetic in this case? I can't picture what you mean; I'm sorry. What is the "zero point" you are referring to? I'll respond though:

- The perfect fifth in equal temperament has the ratio of 1 to the twelfth root of 128, which is no less irrational than the square root of two. Irrationality is not the issue with regard to harmonic relationships; the harmonic relationship is defined more by the whole number ratio it approximates. For instance, the twelfth root of 128 is very close to 3/2. Similarly, in most tonal usage, the (equal tempered) tritone is more or less a stand in for 7/4. The difference is that it is not as closely aligned to this simpler ratio as, say, a fifth to 3/2, or even a major third to 5/4.

- It would not be used so extensively in dominant chords if it did not have a harmonic relationship to the rest of the chord. As a place to modulate it is definitely more "distant" than modulation by a fifth or third. My opinion is that it's actually more strongly numerically related to the original key than the semitone relationship (though most harmony books use the circle of fifths as a metric of distance, and will state otherwise; In modulation, however, the most important factor seems to be how many tones are held common, and how many or not). - Rainwarrior 15:35, 8 June 2006 (UTC)

- I was using "start in unision" in the lay sense, not the musical sense, or the micro (within one vibration) not macro (measured over many vibrations) sense. If two vibrating bodies start moving from their neutral (unstressed) position (easiest to think of two strips of steel clamped in the same vice being twanged together, or reeds of a reed organ); If they are equal length etc, they will sound in unison and continue to move together. If one is twice as long as the other, it will vibrate half as fast (they will sound an octave) and they will move together past the neutral point after one vibration of the longer one, two of the shorter. However, if they are tuned in the ratio of 1: root 2 because the ratio is mathematically irrational, they will never move simultaneously through their neutral points again. Rainwarrior said "the harmonic relationship is defined more by the whole number ratio it approximates." but the ratio of 1: root 2 does not approximate to any other. I think we are at cross purposes here because I am looking at it from a mathematical/acoustic point of view, not a musical/harmonic one. But isn't "the perfect fifth in equal temperament" a contradiction, because a fifth in equal temperatment is not perfect? --Hugh7 23:08, 24 April 2007 (UTC)

- Hugh7, Rainwarrior meant that the equal temperament tritone functions harmonically because of its approximation to just intervals such as 7/5. You're right that two sine waves at an irrational frequency ratio would only cross the middle line at the same time once if sustained indefinitely. I know what you mean. (In fact, they would cross each other an indefinite number of times, but only once per any vertical position.) The ear is forgiving though and tends to hear an interval "as it should be" rather than "as it is". That's why we can listen to someone strumming an out-of-tune guitar and still be able to identify the chord progression (I, IV, V, etc.). It's the same with equal temperament versus just intonation. The ear receives irrational relationships, but tends to overlook the errors and "hear" them as whatever just relationships they are close to. It's hard to prove that, since it deals with the personal experience of perception, but people like Helmholtz found good supporting physiological evidence. A fifth in equal temperament is not "perfect" but it approximates 3/2, which is perfect, so it's "convenient" in harmonic discussions (though false) to speak of a "perfect fifth" in equal temperament. It’s good to remind ourselves of the truth once in a while though.—76.94.244.40 (talk) 00:40, 1 April 2013 (UTC)

- Rainwarrior, it's interesting to note that the reason the tritone retains its width when inverted depends entirely on the fact that it's tuned in equal temperament. The just intervals that the tritone approximates do not retain their width when inverted, and those intervals are most likely the original basis of harmony (not the tempered tritone). For example, 10/7 is wider than 7/5, 16/11 is wider than 11/8, 64/45 is wider than 45/32, etc. You can definitely hear the difference between a tritone and its inversion in just intonation. That means that all those "tritone substitution" progressions in chromatic romanticism and later in jazz are artificial. The F-to-B tritone in G7 is not the same interval as the F-to-Cb interval in Db7 in "real" harmony, so you can't substitute Db7 for G7 in "real" harmony, and you can't quickly modulate from the key of C to the surprise key of Gb by going CMaj G7 Db7 GbMaj. We can only get away with that kind of G7 to Db7 substitution because equal temperament confounds all the many kinds of tritone intervals into a single interval (just as it confounds many major seconds into a single interval, etc.). Equal temperament allowed a freedom of modulation (well, a freedom of “frenetic motility” at least, if you will) but only with the associated costs of a loss of musical accuracy and a restriction of the number of destinations to modulate to (only 12 possible tonal centers instead of potentially hundreds of audibly distinguishable targets). Fortunately, electronic technology makes pitch control easy, and lots of electronic composers are now exploiting the wider pitch resource with increased vigor, joining the much-harder-working acoustic folks (for whom increased pitch variety is always problematic). (By the way you said the tritone is a stand in for 7/4. I think you meant 7/5. 7/4 is a minor seventh interval.)—76.94.244.40 (talk) 00:40, 1 April 2013 (UTC)

Degree of dissonance of the tritone[edit]

I don't think this should be exaggerated, which I think the article did. Persichetti in Twentieth-Century Harmony has what I think is a more usual view:

- It is difficult to classify the tritone or the perfect fourth out of musical context. The tritone divides the octave at its halfway point and is the least stable of intervals. It sounds primarily neutral in chromatic passages and restless in diatonic passages. The perfect fourth sounds consonant in dissonant surroundings, and dissonant in consonant surroundings.

That's more like it, I think. Gene Ward Smith 03:01, 11 June 2006 (UTC)

I just added a sentence in the article based on that book.--Roivas 21:50, 16 November 2006 (UTC)

The Tritone's usage in history[edit]

The tritone is a restless interval, classed as a dissonance in common practice music; even more dissonant than the minor second or seventh[citation needed], and given the name diabolus in musica ("the Devil in music") by some from the early music era to the baroque period, likely because of its unwanted occurrence as F against B when two voices were singing a fifth apart[citation needed]. It was exploited heavily in the Romantic period as an interval of modulation for its ability to evoke a strong reaction by entering the key least related (retaining only two common tones, the least possible) to what occurs previously[citation needed].

I'll try to provide some better information on this. Anyway, this paragraph needs to be improved.

Anyway, you'd think the "key least related" would have no common tones.

The secondary dominant and diminished seventh relations are what facilitates modulation in tonal music. Both of which contain tritones. Not sure what the paragraph above is trying to get at and I think it would just confuse someone who is trying to learn the basics of music theory.--Roivas 22:02, 16 November 2006 (UTC)

- When taking 7 of 12 tones to build your scale, you only have 5 tones left over. So, if you want to pick the most unrelated scale of 7 tones, you have to reuse at least 2 (7-5 = 2). (Though the minor-second modulation also has only 2 common tones.) - Rainwarrior 22:55, 16 November 2006 (UTC)

Okay, two keys with roots a tritone apart have two common notes between them. I get what you mean now. I would make the paragraph a little more clear, that's all.--Roivas 23:54, 16 November 2006 (UTC)

- As for the diabolus in musica stuff, a citation should be really easy to find. If my books weren't packed up in boxes right now I'd put one down for you, but if anyone else out there has, say, the Richard Hoppin Medieval Music, or even the Grout history, check the index for it. You'll find something. - Rainwarrior 23:01, 16 November 2006 (UTC)

- I put in some clarification there--the Diabolus in Musica is not a medieval term (search for it in the Thesaurus musicarum latinum and you won't find anything). I also tried to start a little section on its use in the classical and baroque eras. I think that after the initial definitions, dividing the article by usage historically is important. (I also think that the list of pieces with tritones in them needs to be pruned carefully--naming works without prominent tritones is harder than naming works with them). --Myke Cuthbert 00:32, 28 November 2006 (UTC)

Yeah, I've never been too clear on this. I saw the term mentioned in Walter Piston's "Harmony" when I was flipping through it, but only as a passing comment. Agree on your other points as well.

An answer might be found in this great little collection of papers: Music in the Western World, a History in Documents. I can get it from a local library in the next couple of weeks.

Funny that Black Sabbath's "Symptom of the Universe" wasn't mentioned! That's a great tritone riff. Just kidding.--Roivas 07:05, 28 November 2006 (UTC)

- I have the Weiss-Taruskin Music in the Western World sitting here, but I didn't see anything on the tritone (it avoids music notation for the most part, so discussion of elements such as tritones is sparse). The Strunk volume of documents might have something on this topic, but I also doubt it. --Myke Cuthbert 22:41, 28 November 2006 (UTC)

- Btw -- Nice job on so many edits, Roivas. I want to move the part about the TT in "first inversion" chords from Jeppesen to between the Medieval and Baroque sections, since it's really dealing with 16th century music which played by different rules. We don't yet have a subsection on the tritone's use in Renaissance music. --Myke Cuthbert 03:23, 1 December 2006 (UTC)

Sounds good. Thanks!--Roivas 05:08, 1 December 2006 (UTC)

My suspicion is that people use it because it "sounds cool."--Roivas 22:50, 28 November 2006 (UTC)

- "even more dissonant than the minor second or seventh[citation needed]"

This statement bothers me as dissonant and consonant are fairly subjective terms and the definitions for both tend to change drastically within short periods of time. I know that Hindemith qualifies what you are saying (for his own reasons), but I'm sure I can find sources that say otherwise. Can we make this statement less definite or, at least, qualify it with a source?--Roivas 19:30, 27 November 2006 (UTC)

Occurrences[edit]

If folks would please refrain from adding more and more "tritone occurences" in popular culture, that would be great. It's one of the most ubiquitous musical devices in Western Music. Nothing special about it. Suprised no one has mentioned the English police siren! At least that's sort of interesting.--Roivas 22:08, 3 December 2006 (UTC)

- Agreed. The newest Ravel example seems absolutely silly. A list of Ravel works without tritones would be more interesting. Or a discussion of how Ravel uses it would help someone who comes to this article expecting to learn something. The European siren usage would be a good mention though. --Myke Cuthbert 04:32, 31 January 2007 (UTC)

Can someone...[edit]

Can someone translate the German regarding the tritone in the history section? Not all of us (including me) understand German. bibliomaniac15 05:26, 27 January 2007 (UTC)

- I'm not so fluent, but since I did add the texts, I guess I have some responsibility. :) I am surprised by the "angenehme" and really hope I didn't mistranscribe "unangenehme," but given other things Mattheson has written, it is entirely possible. Also, I added a little section explaining how mi-fa can be a tritone. --Myke Cuthbert 05:11, 29 January 2007 (UTC)

Tritone Substitutes[edit]

With respects to Jazz music, shouldn't someone mention tritone substitutions? (unsigned message)

- An important element not mentioned in the article, but I have little expertise on the issue, so I can't add this section.--Myke Cuthbert 16:40, 24 March 2007 (UTC)

- Currently it's breifly mentioned in the article but I think it deserves some more limelight then what it currently has. Omillas (talk) 21:05, 20 December 2018 (UTC)

Mi contra Fa[edit]

Historically, the interval of the tritone was Mi-contra-fa, not Si contra fa; Si against Fa implies solfeggio thinking, while Mi against fa is hexachordal thinking. Please read the 18th century theoretical examples before changing this again. --Myke Cuthbert 02:15, 20 February 2007 (UTC)

- how exactly does "mi against fa" describe a tritone and not a half step? Der Elbenkoenig (talk) 01:41, 8 October 2011 (UTC)

- The question might just as well be asked the other way around, in which case the answer is "only when mi and fa are in the same hexachord". Mi in the "hard" hexachord (the one running from G up to E with all natural notes) is B, while fa in the natural hexachord (the one from C up to A) is F. The notes F and B form a tritone when F is the lower tone, and a semidiapente (diminished fifth) when B is the lower note. Of course, if you take the hard and soft hexachords (the "soft" hexachord is the one from F up to D with a B-flat), mi in the former is (once again) B, but fa in the latter is B-flat (hence a chromatic semitone, or augmented unison, which in the rules of 16th-century counterpoint is a very different thing from a minor second); the reverse puts A against C (a minor third). The dictum does not really apply to derived (transposed) hexachords, where virtually any interval at all may result from mi against fa.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 02:43, 8 October 2011 (UTC)

most dissonant interval?[edit]

isn't the tritone the most dissonant musical interval? 67.172.61.222 22:48, 9 March 2007 (UTC)

- No. Aside from dissonance being difficult to define in a quantitative way, it shows up in every dominant seventh chord. If anything is "most dissonant", it's probably the minor second. - Rainwarrior 17:33, 10 March 2007 (UTC)

- I'll see your "no" and raise you a "yes for the following reasons"-

- since a tritone divides the octave in half symmetrically, there is no tonal center between the two notes, and it is always unstable regardless of context (from a purely clinical viewpoint, a lack of tonal center is a pretty concrete definition of dissonance, imo).

- a dominant seventh chord is relatively dissonant, but it doesn't always sound out of place, given certain contexts (i.e. building tension to resolve to the tonic or elsewhere or harmonizing with a scale).

- when you play the two intervals as one note after another, there is a pretty obvious difference. going from E to F sounds much different than going from E to A#.

- like all other imperfectly consonant intervals, a semitone can sound perfectly fine in certain contexts. listen to "From the Morning" by nick drake for example. A tritone never sounds melodic.

- finally, since an interval is roughly as consonant as it's inverse (i.e. a fourth and a fifth), a major seventh would have to be similarly dissonant. it is, of course, not especially consonant, but when you play a maj7 chord it's certainly not comparable to what a b5 chord (or a diminished chord) sounds like.67.172.61.222 00:23, 16 March 2007 (UTC)

- Dissonance and consonance are culturally defined terms and don't obey particular universal rules. You could correctly say that an interval was "treated as the most dissonant interval by composer X" or "in period Y" or "in Noh theater" but your ear is not a good judge of universal dissonance. For instance, C->B# is considered a dissonance by most tonal theorists (augmented 7th). Similarly, a bare perfect 4th is definitely treated as a dissonance in nearly all common-practice harmony--it does not have roughly the same degree of consonance as the P5.

- I think I remember reading somewhere that Dissonance can be measured as the least common multiple between two frequencies or something like that; C to B# is anything but dissonant as it is an augmented seventh which is enharmonic to an octave. It is the most consonant interval other than unison.

- Your point about harmonic and melodic dissonances being different beasts is a quite good one. --Myke Cuthbert 01:03, 16 March 2007 (UTC)

- What do you mean by "sounds melodic"? And what is melodic dissonance? Do you have a definition or is this an entirely subjective measurement? And as for "harmonic" dissonance, consider any chord with exactly two semitones and no tritones (either C D♭ D♯ E, or C D♭ E F) and and compare to any chord with two tritones but no semitones (C D F♯ G♯, or C E♭ G♭ B♭♭); which is more "dissonant" subjectively? Or similarly with three semitones (C D♭ E F G♯ A) vs three tritones (C D E F♯ G♯ A♯)? - Rainwarrior 06:53, 16 March 2007 (UTC)

- Rainwarrior, how do you do the sharp and flat symbols? --63.25.21.154 (talk) 11:10, 7 March 2008 (UTC)

Myke and Rainwarrior are right. There is no fixed definition of "most dissonant interval" in equal temperament. It's completely subjective. Maybe if User:67.172.61.222 took beats into consideration he/she may have something going for his/her argument. Even then it wouldn't matter.--Roivas 22:07, 18 April 2007 (UTC)

- I'm inclined to agree with 67.172.61.222. In twelve-tone music, this is roughly how consonance and dissonance play out:

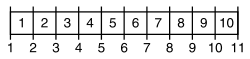

- INTERVAL AND INVERSION:

- Most consonant

- 0 (perfect unison) and 12 (perfect octave)

- 5 (perfect fourth) and 7 (perfect fifth)

- 4 (major third) and 8 (minor sixth)

- 3 (minor third) and 9 (major sixth)

- 2 (major second) and 10 (minor seventh)

- 1 (minor second) and 11 (major seventh)

- 6 (augmented fourth) and 6 (diminished fifth)

- Most dissonant

- I imagine the only thing that changes culturally is exactly how strict the definition of "consonant" is (in medieval times only 0/12 was consonant, gradually growing to include 5/7, 4/8, and 3/9)--but that still gives you a pretty clear indication of where every interval falls regarding sonance. Joe routt (talk) 04:40, 27 May 2008 (UTC)

- Can you cite a source for this information per Wikipedia:Citing sources? Hyacinth (talk) 06:09, 27 May 2008 (UTC)

- Huh? 4/8 is 1/2, aka an octave, which is consonant no matter what culture or time period you're looking at. 3/9 is 1/3, octave-equivalent to a perfect fifth. 0/12 isn't even possible (I guess it could mean a single string with no harmony at all). Not sure what you intended. — Gwalla | Talk 17:48, 27 May 2008 (UTC)

- You misunderstand me. When I refer to 0/12, 5/7, etc, I am not referring to fractions. In this case 0/12 would be an interval of 0 semitones (unison), paired with its inverse, an interval of 12 semitones (octave). Likewise, I used 5/7 to mean a perfect fourth and fifth. Allow me to rephrase myself: In medieval times, only unisons and octaves were consonant, gradually growing to include perfect fourths and fifths, and major and minor thirds and sixths. I hope that clarifies things. Joe routt (talk) 00:06, 28 May 2008 (UTC)

Historical uses[edit]

Wouldn't it be helpful to make it clearer that the equal tempered tritone familiar today is not the same as most older tritones? Close, perhaps, but I wonder how easy it is for people today to hear an equal tempered tritone and think that is the sound that was supposedly the devil in music and something to be avoided. I know I had that misconception for a long time. As I understand it, there are multiple types of tritones found in early temperaments and in just intonation, none of them quite the same as that familiar today. If so, it strikes me as potentially misleading to talk about the tritone's history as if it is a single thing. Does this make sense? Also, I have the impression that the "devil in music" thing was less about how dissonant it was and more about how the tritone's existence made it clear that a "perfect" system of harmony and tuning was impossible. Pfly 06:53, 12 March 2007 (UTC)

- There is no historical evidence for the Devil in Music idea going before the middle Baroque era, so it's hard to say how temperament would have affected this idea. The tritone's unacceptability in certain contexts comes from the way it substitutes for a perfect fifth (or, more rarely, P4) and not from the way one tritone differs from another. Discussions of the size of the semitone, tone, major and minor thirds, etc, are common. Discussions of the size of the tritone are rare. --Myke Cuthbert 16:12, 12 March 2007 (UTC)

- I just looked up what I could find on the topic in W.A. Mathieu's "Harmonic Experience" book, checking pitch names at the Scala site [1]. Again, I am still too unsure about this to edit the actual page but thought I'd put some thoughts here. Interestingly, Mathieu makes almost no mention of the word "tritone" in his book. His main theme seems to be showing out equal tempered intervals (ET) "stand in" for the more consonant justly tuned ones (JI) described with ratios; and that one ET pitch can "stand for" more than one JI pitch, depending on the harmonic context; and that the context can set up an ET pitch to stand for one JI pitch but then continue as if it was a different JI pitch. He makes a good case for this being one of the major strengths of ET and something composers have exploited, knowingly or not, for the way it can "trick the ear" (ie, sound cool). So in this framework, the term "tritone" is not very useful since it does not indicate what JI pitch is involved. So instead he almost always refers to tritones as "augmented fourths" or "diminished fifths", or less frequently, other terms. In ET an augmented fourth is the same pitch as a diminished fifth; the tritone. But in harmonic progressions, the two have different functions. Anyway, I made a list of the various JI pitches for which the ET tritone could "stand for" harmonically. Some are purely theoretical (too hard to set up a harmonic progression that would bring it out), but at least 4 are heard as different, maybe 5:

- The augmented fourth F# 45:32 (590 cents) (aka "diatonic tritone"); the "diminished fifth Gb 64:45 (610 cents) (aka "2nd tritone"); the eleventh partial "undecimal semi-augmented fourth" F# 11:8 (551 cents); and the "grave fifth" or "wretched pa" 40:27 (680 cents), this last being more a "bad fifth" than a "tritone". Other intervals in the tritone range that are more theoretical than useful include "acute fourth" 27:20 (520 cents, more a bad fourth than tritone); the 555 cent quarter-tone; "classic augmented fourth" 25:18 (568 cents); "septimal tritone" 7:5 (583 cents); and the "Pythagorean tritone/augmented fourth" 729:512 (612 cents).

- Anyway, I was just curious enough to look up stuff this far, but must attend to other things. Unsure whether this stuff is useful for this page (though its been very useful to me personally in understanding harmony), but thought it worth posting here. And yea, the "devil in music" comment was something dredged up from memory and probably just a theory I randomly speculated about once rather than something real. I'll keep my eye out for references on the topic though! Pfly 19:46, 12 March 2007 (UTC)

- Sorry I jumped too much on the "devil in music" aspects of your first post. I think there is a lot of important information in your second comment which should be added to the article. A couple of thoughts though. Many of the names of pitches on the Scala site are not conventionally used, and are in fact historically inaccurate ways of attributing a name to an interval. The one that jumps out at me immediately is "wretched pa" -- "pa" is an Indian note name (from Sa to Pa is basically from Do to Sol), so no pre-ET European composer would have been thinking of their interval as any form of "pa". The terms I recognize are "septimal tritone" and "Pythagorean tritone". In many tuning systems, there would be all sorts of different A4s and d5s in use which don't have conventional names. I don't know which parts of the article would need to be modified to take account of these subtleties, but I suspect not all of it.

- The part of the article which I think needs the most work is the use of the tritone from about 1650-1800, and as this is the period where ET thinking became dominant, it may be the best place to add your information. --Myke Cuthbert 19:22, 14 March 2007 (UTC)

- Hmm, having research a bit more, I've gotten the impression that of the JI pitches I mentioned only the 45:32, the augmented fourth, is what the word tritone has mostly meant, historically. Maybe the diminished fifth as well, but I'm not so sure anymore. Today in ET I'm sure both are often called tritones due to enharmonic equivalence. The 11:8 pitch is supposedly a possible "blue note" rather than a "tritone", if it is harmonically used at all. The 729:512 Pythagorean tritone might count as a historically significant tritone, if it is not merely a theoretical construct. The rest of the pitches I mentioned seem better called fourths or fifths rather than tritones, except perhaps the 7:5, which as I understand is probably a modern theoretical invention anyway.

- So I take it back! Except perhaps something about the difference between an aug4 and a dim5 and how they relate to the term tritone historically, and how once upon a time, the pitch of the tritone was different from that in common use today (the "wretched pa" term comes from Mathieu's book -- he uses Indian sagram terms for prime factors, "pa" being equivalent to "Pythagorean", but a lot easier to say and write!) Pfly 23:51, 14 March 2007 (UTC)

- 7/5 is far from modern. Offhand, I remember that Giuseppe Tartini wrote about them and a notation for them, but I'm reasonably certain there are earlier references to it. The tuning of a dominant seventh as 4:5:6:7 is really quite natural, and can be frequently heard in vocal quartets, string quartets, and small brass ensembles. It would be strange to think that this extremely stable chord was not used before modern times. - Rainwarrior 05:41, 15 March 2007 (UTC)

- FYI I added a brief note about how the tritone is called "The Devils Interval". Jaydubya93 (talk) 12:21, 22 March 2014 (UTC)

Sympathy for the Devil's Interval[edit]

I've always thought that the lowest note in the repeated bass line of the Rolling Stone's "Sympathy for the Devil" sounds like "the wrong note". Someone suggested to me recently that maybe they were using "the Devil's interval". Does someone know if this is true? If so, it seems like that fact would be a worthy addition to that article (and maybe this one). - dcljr (talk) 03:13, 21 March 2007 (UTC)

- No, the wrong note is an 'A' beneath an E major chord. Usually a bassist should play a 'B' in this context, but here he plays an 'A'. The interval is a perfect-fourth which sounds wrong because it's not part of the harmony (producing other dissonant intervals, like a major second/ninth and a major seventh, but no tritones). - Rainwarrior 05:37, 21 March 2007 (UTC)

Hugh7 trivia[edit]

It seems to say more about Lillian Hellman or Dorothy Parker than about the tritone. Consensus to remove? --Myke Cuthbert 19:39, 23 April 2007 (UTC)

- Yes, it's amusing and characteristic of Parker's wit but obviously pretty irrelevant here. Rigadoun (talk) 19:04, 24 April 2007 (UTC)

Isn't trivia always more or less irrelevant? Rather than delete, if you must, please move it to Dorothy Parker or Lillian Hellman --Hugh7 23:15, 24 April 2007 (UTC)

- I might be more against trivia sections in articles than others, but I think this piece of trivia might not have a good place in Wikipedia. There are many great jokes about diminished fifths, but I don't know where they should go. Though I think an article on humorous statements made about music theory would be a fine addition to WP, and I'd definitely want to contribute. --Myke Cuthbert 01:06, 25 April 2007 (UTC)

Tritone as irrational ratio[edit]

That the equal-tempered tritone stems from an irrational number ratio does not explain it as a dissonance. Except for the octave, all intervals in ET are irrational numbers. The perfect fifth, for instance is 1.4983070768766..., yet it is treated as a consonance. --Myke Cuthbert 01:06, 25 April 2007 (UTC)

We almost need another name for the frequency exactly half way up or down the octave whose frequency is the square root of two times the tonic. "tritone" doesn't quite cover it because it depends which kinds of tone it's three of. ET is an approximation to Pythagorean perfect intervals. The "perfect" fifth sounds consonant in ET and so "is treated as a consonance" because for most ears it is near enough to 1.5. Using the figure above, the ET "perfect" fifth from A440 is 659.2551138257 Hz, the true perfect fifth is 660, so they would beat together at 0.745 Hz, a slow throb that would not be perceived as "out of tune" by most people (two slow even for a vox humana effect). The true root-2 interval is not near to anything. That's the point I've been trying to get across. --Hugh7 08:18, 25 April 2007 (UTC)

- It's near to several just intervals, like 7/5. Furthermore irrationality is certainly not the cause of dissonance, and equal temperament is not the cause of the tritone's dissonance. The tritone is still dissonant in just intonation (and it was known to be dissonant long before temperament began). - Rainwarrior 16:05, 25 April 2007 (UTC)

- 7/5 is pretty remote for a just interval, being the ratio of two non-trivial prime numbers. Two vibrating bodies tuned to 7:5 will pass through their rest-points in the same direction only every 35 cycles, which is rather too many for the ear to "count". Do people hear that as "more harmonious" than an accurate 2^½:1? --Hugh7 07:49, 1 May 2007 (UTC)

- And 6/5 only once every 30, but that one's long been catalogued as a consonance, and what about 7/4, shouldn't that be by your logic more consonant than 6/5? The lowest common multiple isn't really a measure of consonance. Dissonance and consonance are largely contrapuntal functions, for instance, 4/3 is "dissonant" in much theory. 7/5 is dissonant in tonal use in general. This has nothing to do with the fact that 7/5 is an audibly pure and stable interval and 2^1/2 is not. If you put it in the context of a justified dominant seventh chord 4:5:6:7, compared to the ET version it is profoundly stable. - Rainwarrior 17:37, 7 July 2007 (UTC)

- 7/5 and 10/7 are relatively consonant. They just sit there nicely. However, if you stack three large major seconds (9/8), which is what a tritone would literally be (an interval the width of three tones stacked), which is the same as stacking six perfect fifths and subtracting three octaves, or basically stacking prime 3 six times ignoring octaves, you get 729/512 and its inversion 1024/729, both of which are pretty dissonant. That's why the tritone is historically considered dissonant. It has to do with reaching far away using repetitions of the same prime 3, not with reaching nearby for those close friends prime 7 and prime 5. As another illustration, even stacking prime 3 just four times is dissonant. Adjusting for octaves, that gets you the Pythagorean Major Third, 81/64, which is more dissonant than 5/4, even though 5 is a higher prime. 38.86.48.38 (talk) 06:06, 2 May 2015 (UTC)

Musical examples (getting out of hand again...)[edit]

I think that the musical examples section is getting a little out of hand again. My suggestion: can we make the section "Music which explicitly mentions the tritone" which would include "Slayer" or call the section "Unusual uses of the tritone," which would include the retuned timpani in Fidelio (extremely unusual for its time). And move the rest either to a new article "Prominent uses of the tritone" or more generally, "Prominent uses of particular musical intervals." Thoughts? --Myke Cuthbert 01:06, 25 April 2007 (UTC)

- I cut the list down to pieces in which the tritone appears unusually or self-referentially. Yes, there are lots of Metal pieces which feature tritones, but also lots of country songs, Lawrence Welk ballads, etc. The Slayer reference could be returned, but does it use a tritone prominently anywhere except in its name? The "Charmed" example seemed the only one from popular culture which explicitly linked a tritone to specific "evil" effect. I think that if we had a musical example of Purple Haze or the opening chords of Elfman's "Simpsons," then they'd be worth mentioning in section on how the tritone is commonly used, but they're no more unusual than hundreds of other examples. --Myke Cuthbert 21:02, 12 May 2007 (UTC)

- Actually (having just tried to give the article some sense of order), I think the best thing would be to incorporate these in the main text, noting why they are historical. In particular, this would be useful for the heavy metal examples (about which I know nothing)...which songs were the "first" to use the tritone that was "practically endemic" to black metal (I deleted that phrase, as the wealth of examples from other kinds of music make it clear there is no endemism here) and how did it become so associated with the genre? In general, instead of a list, putting in text gives you more context about why they are notable (e.g. first of its kind in such-and-such genre, or widely familiar, etc.). Maybe I'll get around to it someday. Rigadoun (talk) 05:14, 12 November 2007 (UTC)

The musical examples should at the very least say whether the tritone is used harmonically or melodically, so readers will know what to listen for. — Gwalla | Talk 04:39, 29 February 2008 (UTC)

Slayer does extensively use "Diablolus in Musica" throughout their work and hence the name for the album. One of the guitar tab books (I believe it's the one for "Decade of Aggression") points this out several times. Also, one of the former engineers for Macintosh stated that the original Mac startup sound is a tritone in the "Welcome to Macintosh" documentary. Henningp (talk) 08:06, 7 December 2009 (UTC)

It may actually be a good idea to refactor the article a bit and eliminate the examples section in favor of an "in popular music" section not in list form, and maybe a "non-musical uses" section for things like car horns and air raid warnings. As it is, it's a bit scattershot, not only acting as a magnet for trivia but also redundancies (such as Danse Macabre, who is mentioned in the history section). — Gwalla | Talk 21:09, 29 January 2010 (UTC)

I generally hate examples but Wikipedia's own article for Black Sabbath's Black Sabbath goes out of its way to mention the tritone; the central, three-note riff is a "devil's tritone", presumably selected because of the song's subject matter. It's probably the quintessential example of a tritone in metal music. 146.90.225.67 (talk) 20:35, 6 September 2012 (UTC)

function of chord[edit]

can someone please add a section to explain its function? Jackzhp 20:53, 7 May 2007 (UTC)

- Function of what chord? Hyacinth 20:56, 7 May 2007 (UTC)

World of Warcraft[edit]

I thought this info from the recent Blizzcast about the use of the Tritone in World of Warcraft was interesting:

- "There's an interval in music known as a tritone ... it's been referred to in history as the "devil's interval" ... it's not quite consonant and it's certainly not terribly dissonant and it makes people feel ... uneasy without being harsh or jarring so I wrote all around that interval ... I'm playing a lot of games with that interval ... that interval and the cello ... that pallet of choir and harp ... blended all together to create the vocabulary for the Blood Elves." — Brower, Russell (2008-08-07). "How the music in World of Warcraft has evolved since the game began" (Interview). Interviewed by Nethaera, Blizzard Inc. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

{{cite interview}}: Unknown parameter|program=ignored (help)

Since this is the only citable mention that I know of of the use of the tritone in modern media, I thought it would be worth including. -Miskaton (talk) 15:00, 12 August 2008 (UTC)

- This really seems too trivial to mention. The only recent citable mention of the tritone? Really? — Gwalla | Talk 16:00, 12 August 2008 (UTC)

- Hmm, I agree with Gwalla. There certainly isn't any shortage of modern writing and scholarship on the tritone. Now it would be wonderful if someone had the time do dig through them and expand the article, but that's a different matter entirely. :) --Blehfu (talk) 18:13, 12 August 2008 (UTC)

The ratios in just intonation[edit]

The tritone was never 5/7 in either Medieval or Renaissance music when the term first arose. In the medieval period, it was 512/729 (8/9 x 8/9 x 8/9 --three tones of a tritone) in the content of Pythagorean tuning. In that tuning, all other intervals are 2/3 and 3/4. 512/729 is startingly dissonant in that context. The so-called equal-tempered in so tame in comparison that most contemporary musicians cannot understand what the original fuss was all about.

In the Renaissance, it was 32/45. A whole tone (8/9) higher than than the just major third (4/5). Again, in the context of Renaissance just tuning, it seems rather jarring.

The big problem of the tritone in the original choral contexts is that it tended to disorient the chorus and its sense where the correct pitch should be placed. 71.210.0.143 (talk) 16:35, 10 April 2009 (UTC)Robert Ross

- The article didn't say that 7/5 was used in the Medieval or Renaissance periods, it simply listed 7/5 among just tritones. Hyacinth (talk) 08:12, 29 September 2010 (UTC)

17:12[edit]

What about 17:12? It's only slightly sharper than the equal tempered tritone. 151.103.236.139 (talk) 18:40, 27 September 2010 (UTC)

- What about it? Do you think it should be added to the article? Hyacinth (talk) 22:05, 28 September 2010 (UTC)

Black sabbath and metal[edit]

It is definantly notable that a straight tritone is the main riff of the song "black sabbtah" by the epnonymous band, and that metal music in general is based around the tritone and its uses in the pentatonic scale and to a lower extent the blues scale. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 216.163.3.121 (talk) 06:22, 20 April 2009 (UTC)

- Agreed, even if a decade late. I am surprised that this is not discussed in the article. When I think of tritone out side of jazz, this is the exact song I think of. The tritone is foundational to metal. Jyg (talk) 05:51, 20 April 2020 (UTC)

I am unable to understand this article[edit]

Hello, I am kind of Newbie and I am aware a Simple English version is being written. Still I started reading this article and there were scores of words that do not form part of my vocabulary.

Love, Andreseso (talk) 10:39, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

- Such as? See Help:Contents/Links. Hyacinth (talk) 21:09, 22 May 2009 (UTC)

Like much of the music theory at Wikipedia, it only makes sense if you already know what it means. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 72.94.170.222 (talk) 17:49, 3 April 2011 (UTC)

- Could you be a little more specific? I notice, for example, that User:Paolo.dL has recently begun making some changes in the introduction. Do you feel these are improvements, or have they made the article less comprehensible for you?—Jerome Kohl (talk) 22:34, 3 April 2011 (UTC)

Car Horn[edit]

Aren't car horns deliberately tuned to the tritone? This must be the main reason why they're duophonic. Worth mentioning? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 81.109.11.182 (talk) 13:37, 8 October 2009 (UTC)

- yes, i think i read that somewhere, car horns are usually tritones, and they're intended to be annoying, so someone's opinion is that this is the most dissonant interval —Preceding unsigned comment added by 170.170.59.138 (talk) 20:48, 26 October 2009 (UTC)

Some car sirens use tritones, but normal car horns are a single note. (Usually natural F) 151.103.236.139 (talk) 18:34, 27 September 2010 (UTC)

Toward an English version of this article[edit]

In an edit summary, User:Paolo.dL wrote: "Thank you Jerome Kohl. Would you mind if I delete the reference to German language? Knowing it comes from Latin is more than enough. Specifying how the tritone is called in other languages does not seem relevant in this article."

- Please do delete the reference to the German/Latin term, or else I will be forced to list the Spanish, French, Albanian, Japanese, etc. terms as well. I'm not actually sure that the Latin term itself has any relevance in English. As a native English speaker myself, with graduate degrees in music earned at American institutions, I have never heard it used outside of musicological seminars and articles discussing Latin treatises.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 16:40, 4 April 2011 (UTC)

- I found the statement in the first section of the article. It was inserted by someone else, and I just moved it in the introduction. I believe you misinterpreted it: it did not state that "tritonus" was the Latin term. It listed it as another term (sometimes) used to indicate the tritone. Obviously this meant it was used in English, as this article is in English and all synonyms listed in the intro are supposed to be in English, unless otherwise specified. Initially, before my edits, the text specified that the term was often used in German as well, but I thought it was irrelevant information, and deleted it. Later, it was you who wrote it came from Latin, and inserted again the reference to German language! So, I really cannot understand why you wrote: "delete the reference to the German/Latin term, or else I will be forced to list the Spanish, French, ... terms as well". However, I am glad that you changed your mind. It's good to know that, in your opinion, this term is so rare that it does not deserve to be mentioned. I agree: let's delete it. Paolo.dL (talk) 18:50, 4 April 2011 (UTC)

- I did understand all that. When you moved that text, your edit summary questioned whether it was a German or Latin term. It is the term used in German (as well as in Dutch, Danish, Finnish, Norwegian, and Swedish, as can be determined from the interwiki links to the corresponding articles on the Wikis in those languages), though of course it is a borrowing of the Latin word. Your position is perfectly correct, in my opinion. I believe that whoever thought "tritonus" is used in English was wrong. My reference to adding other languages was a (poor) attempt at humour. My apologies for leading you astray.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 19:15, 4 April 2011 (UTC)

- I found the statement in the first section of the article. It was inserted by someone else, and I just moved it in the introduction. I believe you misinterpreted it: it did not state that "tritonus" was the Latin term. It listed it as another term (sometimes) used to indicate the tritone. Obviously this meant it was used in English, as this article is in English and all synonyms listed in the intro are supposed to be in English, unless otherwise specified. Initially, before my edits, the text specified that the term was often used in German as well, but I thought it was irrelevant information, and deleted it. Later, it was you who wrote it came from Latin, and inserted again the reference to German language! So, I really cannot understand why you wrote: "delete the reference to the German/Latin term, or else I will be forced to list the Spanish, French, ... terms as well". However, I am glad that you changed your mind. It's good to know that, in your opinion, this term is so rare that it does not deserve to be mentioned. I agree: let's delete it. Paolo.dL (talk) 18:50, 4 April 2011 (UTC)

Evident logic fault in the introduction[edit]

I recently rearranged the article to make the introduction more complete and more easily understandable. However, I did not fix a logic fault which was already present in the text (I just moved it from first section into the intro). The logic fault is easy to detect: the "traditional" definition, given in the first sentence of the intro, clearly implies that both the augmented fourth (A4) and the diminished fifth (D5) are tritones, as both span 6 semitones (3 tones). However, the article states that D5 should not be called a tritone (unless A4=D5, as in 12-TET). There are three possibilities to solve this fault:

- We accept the definition as it is: simple and clear (tritone = 3 tones = 6 semitones), and as a consequence we also accept that both A4 and D5 are tritones (even in tuning systems which assign them different sizes).

- We make the definition stricter. In short: tritone = A4. For instance: "the tritone is an interval spanning 3 tones, and encompassing ONLY 4 staff positions".

- We say that both definitions 1 and 2 are used by different authors. In this case, we also need to decide what one we give first, according to some valid criterion (the most commonly used one?).

In my opinion, the definition tritone = 3 tones = 6 semitones is correct. But since I trust the editors who wrote this article, I suspect that the strict definition tritone = A4 is ALSO true. So, I would discard solution 2, and suggest either the first or the third solution, but this is only my personal opinion, and I do not have enough information to take a decision. I need the opinion of an expert to fix this logic fault.

Paolo.dL (talk) 17:09, 5 April 2011 (UTC)

- As with so many terms (not just musical ones!), the exact definition for "tritone" varies with time and, perhaps, place. The definition in the lede paragraph is the usual modern definition, which refers to the absolute distance in an equal-tempered conception (not necessarily in 12-EQ tuning) of the pitch space. This definition also applies in many historical periods where an equal-tempered conception is not applicable. When a distinction is made between "tritone" and "diminished fifth", it implies one or both of two things: (1) the absolute distances are different (because of the non-12-EQ tuning system used), or (2) the interval species are different. The latter condition is of particular concern to music theorists of the 16th century, when tuning debates were also of considerable importance. At that time, a sharp distinction was made between the tritonus which, as its name states, contains three consecutive whole tones, and the semidiapente (diminished fifth) whose name means "short of a (perfect) fifth" (not "half of a perfect fifth") and which is divided as semitone–whole tone–whole tone–semitone. This matters because of the types of semitones and whole tones used in just intonation, where two semitones do not necessarily add to exactly a whole tone. (Zarlino explains in his Istituzioni armoniche that in this context "semi" does not mean "half", but rather "less than", "falling short of". Therefore "semitone" means any interval in the range of half of a major second.) Interestingly, for earlier theorists (in the 13th century, for example) this was not an issue and they, like most modern theorists, used the word "tritone" to describe both the augmented fourth and diminished fifth. I qualify "modern theorists" with the word "most" because, although this applies to beginning-theory textbooks and most other contexts, just intonation has again become a concern for a certain number of theorists in the 20th and early 21st centuries, who make the same distinctions as their 16th-century forebears. This article as it stands does not appear to go into this (and of course some proper references would need to be found), but it is already so complicated, turgid, and technical that it has earned cries of "I can't understand this!" This poses a bit of a problem: how not to sacrifice accuracy while at the same time reducing the complexity. This seems to be something of a specialty for you, Paolo—or at least, I have seen you tackle this kind of problem before in music theory articles—so, for the moment at least, I shall stand back and watch the master at work.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 17:55, 5 April 2011 (UTC)

- Thank you for this outstanding and extremely interesting contribution. I will study interval species ASAP. In the meantime, I am not convinced (yet) that there is a difference between tone+tone+tone, semitone+tone+tone+semitone, or semitone*6. This is because "tone" is as ambiguous as "semitone". I mean, they are not specific intervals, but just "interval types" (the 12 semitones, 12 tones, 12 intervals composed of 3 semitones, etc.). In other words, unless you use 12-TET or a similar tuning system, there's no such a thing as a semitone, tone, "1.5-tone", "bi-tone", "2.5-tone", and tritone of fixed size... As explained in Pythagorean tuning, 1/4-comma meantone, and 5-limit tuning, every interval type in these tuning systems (except for unison and octave, of course) has at least two possible sizes. I'll think more about this. It may take time before I understand 100%. Paolo.dL (talk) 18:45, 5 April 2011 (UTC)

- It is a confusing topic, to be sure, and this may be an argument against even mentioning it in this article. However, in Zarlino and other 16th-century theorists, there is never any question of arbitrarily mixing the different sizes of tone and semitone. The specific use of the major and minor varieties of each is determined by the tuning system used—in Zarlino's case, what he calls the Ptolomaic syntonic diatonic. In any case, in most varieties of just intonation, the minor semitone is chromatic, and the major semitone diatonic, and the species of the semidiapente includes only major semitones, for example.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 19:00, 5 April 2011 (UTC)

- Yet we do have a problem. We did not explain the reason why D5 is not a tritone. Everybody can easily understand or read elsewhere that D5 spans 6 semitones, so it clearly meets our definition of tritone. Even if we simply use tritone = 3 tones, rather than tritone = 3 tones = 6 semitones, everybody can see in our main article about intervals (Interval (music)#Main intervals) that both A4 and D5 span 6 semitones. By the way, both are classified as tritones in that table. The notion that 1 tone = 2 semitones (which implies 3 tones = 6 semitones) is too elementary and intuitively appealing to be ignored altogether. Paolo.dL (talk) 19:22, 5 April 2011 (UTC)

- I see your point. The problem, then, is "our definition", which is drawn from a 12-tet conception of pitch space (according to which, properly speaking, our interval under discussion should be simply called "6"). It is becoming increasingly clear why beginners are finding it difficult to understand this article. "Tritone", on the surface of it, ought to mean "three tones", yet we are debating whether it is four or five, and whether four and five are really the same thing. Have we gone completely mad?! Well, no, because of course the entire terminological apparatus was devised under a system in which there were not twelve divisions of the octave, but seven (even if unequal ones). The conflict is between the historical (etymological) explanation, and the one that assumes common music-making practice of today. Surely the latter ought to be the starting place, if for no other reason than this is what most beginners coming to this article will be assuming. Explaining why D5 might not be regarded as a tritone is a more refined level of explanation, and should be relegated to a later part of the article, in my opinion. Under this plan, the lede and main definition can, I think, ignore this distinction, though the beginner still may find it confusing to learn that the interval may be either a fourth or a fifth. Quite apart from the historical issues, we need to keep in mind that musical context still may make a distinction, especially if we are going to keep on describing the tritone as a "dissonance". Even the beginner is entitled to know why a G4–C♯5 tritone resolves to F4 (or F♯4)–D5, whereas as G4–D♭5 tritone resolves instead to A4 (or A♭4–C5.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 21:46, 5 April 2011 (UTC)

Ok. Thank you for the info. Everything you wrote makes sense. Let's try to be consistent with the intuitively appealing definition of "whole tone" = 2 semitones = either M2 or d3 (where M2 includes, in just intonation, both lesser and greater M2). Fortunately, this is also the definition given in Whole tone. In this case, are we sure that there is no simple way to write the strict definition of "tritone"? Can we write, for instance, that a tritone is, for some authors, just an interval composed of 3 whole tones (= 6 semitones), i.e. either a4 or d5, and for others, more strictly, an interval composed of three M2's, i.e. an A4? (I am just guessing; I did not verify: does this imply an A4?) Paolo.dL (talk) 15:26, 6 April 2011 (UTC)

- At first glance, this formulation ("for some authors") seems to cover the situation admirably. The only thing I might suggest is that "composed of three whole tones", taken literally, could still be read as meaning "three M2s", the parenthetical equation to six semitones notwithstanding. What we are struggling with here is the contrast between an absolute distance (half an octave, measured on a logarithmic scale of course) as opposed to an interval measured by counting along the steps of a diatonic scale segment. In the former case, it would be just as true to say "3 whole tones (=8.5 seventeenths of an octave)", or any other mathematically equivalent expression, though this would hardly be helpful to anyone. In the latter case, we must assume that the reader already knows (or can discover this from a link to Diatonic scale) that the equivalent of a tritone can only be found as TTT or STTS, and not (for example) TSTS, or SSTT.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 19:43, 6 April 2011 (UTC)

I managed to grasp everything you wrote, and it makes sense. Just a note: as far as I understand, it is not always true that "the equivalent of a tritone can only be found as TTT or STTS". I guess this is true only if you use a diatonic scale (such as the Ptolomaic syntonic diatonic used by Zarlino, I guess), or a similar scale with less than 12 pitches, and if you accept an important condition:

- always decompose the tritone into existing incomposite intervals,

where existing means that they are formed by notes which exist in the scale (for instance, C# does not exist in C major diatonic scale, so the semitone C-C#, and the tone B-C# do not exist in that scale), and incomposite means that the notes are adjacent (so an interval is incomposite if no intermediate note exists in the scale between the two ends of the interval). Using the above mentioned conceptual framework:

- If you use a diatonic scale, there's only one interval which can be decomposed into 3 adjacent existing and incomposite tones; this interval is an A4 and the 3 tones are all M2. (notice that without your help I would not have been able to deduce this from the article)

- However, interestingly, if you use a chromatic scale, the most complete decomposition of a tritone is into 6 semitones. The decomposition into 3 tones is possible and legitimate (because the 3 tones exist in the scale), but it is an incomplete decomposition, as all tones are "composite" intervals in a chromatic scale, and can be further decomposed into semitones. As a consequence, you can always find 12 "tritones" (intervals formed by 3 tones) in a chromatic scale. 6 of them are A4, and the other 6 are d5.

So, depending on the scale you use (diatonic or chromatic), the definition TT = T+T+T takes different meanings. Do you agree with this conclusion? Am I still missing something? — Paolo.dL (talk) 16:43, 12 April 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, both accurate and elegantly put. The terms "existing" (not a usual music-theory term, but useful in this context) and "incomposite" (a usual theory term but ordinarily found only in discussions of ancient, medieval, and Renaissance tuning theory) will need to be defined for the benefit of the beginner. Equally for the beginner's benefit, it should probably not be mentioned that the identical sounding interval cannot be called a tritone if the existing intervals are drawn from, e.g., 10-equal or 14-equal tuning, where the octave divided exactly in half is made up of interval of 5 and 7 "semitones", respectively.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 23:42, 12 April 2011 (UTC)

Fixed[edit]

I dared to edit, according to Jerome Kohl's explanations and advices. I believe this fixes the logic fault. I did not use the words "existing" and "incomposite". If you think the article can be made clearer by using these terms, feel free to edit. I used the terms "strict" and "broad" to identify the two interpretations of the classical definition: TT = T+T+T. I don't know whether these terms are also used in the literature or not, but they seemed to be appropriate. I am sincerely grateful to Jerome Kohl for his outstanding contributions. I believe his historical review deserves to be published in the article. Paolo.dL (talk) 14:54, 13 April 2011 (UTC)

Ridiculous Encyclopedia entry: “Tritone”[edit]

With so many sensibilities affected on reading the absurd Wikipedia node, Tritone (music theory), I'm nearly as troubled for indecision over which notion needs addressing. I'll concede, to focus on that which is likely most relevant.

The resource, Wikipedia, is an Encyclopedia. An encyclopedia is a collection of knowledge essentials. The article, although accurate perhaps, is grossly overstated in this context. If Wikipedia were an Encyclopedia of Music Theory then, maybe, this node-- as authored, in its current state (20110711) -- is an appropriate candidate.

Analogizing the notion: the reader who seeks a general understanding of the “tritone”, who happens upon this /article/, is likely to become confused about it. If he or she was not already confused, there's a good chance that this article will accomplish it. Likewise, if the reader is confused, seeking a better understanding, this article is not going to satisfy.

In the context of a contemporary encyclopedic resource, to provide information beyond the scope of general education is in high risk of self deprecation of the greater volume, as is clearly illustrated here.

Jsabarese (talk) 10:39, 11 July 2011 (UTC)

- Wikipedia contains articles about any topic. There's no restriction. We have detailed separate articles about any musical interval.

- In my opinion, this article is quite exhaustive, useful to both beginners and experts, and cannot be made significantly clearer. Unfortunately, the definition of the term tritone is particularly complex, as it needs to refer to a crazy naming convention, which is widely accepted and commonly used in music theory. The article explains everything, but cannot be completely understood unless you study that naming convention, for which a link is provided. We did not create that naming convention, but we are forced to use it. If you don't like it, you can either ignore it, and accept you won't ever be able to understand music theory, or study it.

- Paolo.dL (talk) 12:07, 11 July 2011 (UTC)

- While I disagree that the article, itself, is ridiculous, I do agree that the text of the article could only be understood by those who already know the subject matter.

- I reject the assertion that this article is useful to beginners. I was talking with a friend of mine and he was helping me understand keys and scales and such and he mentioned the Devils Chord. So I came to WP to look it up and did not recognize anything he was telling me. I knew what I was looking for and I was still unsure if I had the right article until the Historical Uses section.

- I also reject the assertion that it cannot be made more clear. We have articles on here explaining any number of things, to think that any concept can't be made clear is contrary to Wikipedia's mission. To paraphrase an old addage "It is a poor teacher who blames his students" Padillah (talk) 18:29, 7 November 2012 (UTC)

- Since this point has been debated already at considerable length, and the article has been edited with this complaint in mind many times since it was first lodged quite a long time ago now, it would be useful to have some examples of just what you find still could "only be understood by those who already know the subject matter". Without such guidance I am at a loss to know where to begin. For example, you name something called "the Devils Chord", a term I have never before heard and which I cannot find in this article, either, although I do find a reference to the expression "diabolus in musica" as a nickname for the interval of a tritone. Are you trying to say that "chord" here would be clearer to the layman than "music" or "interval"? As far as I can see this would increase, rather than decrease confusion. As another old adage has it: "It is a poor critic who waves his hand at the world and says, 'something isn't right here, fix it'".—Jerome Kohl (talk) 19:05, 7 November 2012 (UTC)

- OK, how about the first sentence?

In classical music from Western culture, the tritone is traditionally defined as a musical interval composed of three whole tones.

- So a tritone has three notes in it? Is that what you're saying? You mean to say you honestly think some person off the street will understand this with little to no problem?

- And the second sentence doesn't help:

In a chromatic scale, each whole tone can be further divided into two semitones. In this context, a tritone may also be defined as any interval spanning six semitones.

- So is it three notes or six notes? Why introduce a level of complexity in the second sentence before clarifying the first sentence?

- And there is the interchangeable use of "tone" and "pitch" as in the beginning of the second paragraph:

Since a chromatic scale is formed by 12 pitches, it contains 12 distinct tritones...

- And I am not confusing the use of tone within the word tritone with the word tone. I am pointing out that in the first sentence the word for what a layperson would call a note or sound is "tone" ("musical interval composed of three whole tones"). The word used then switches to pitch in the very next paragraph. This is confusing for a layperson. As a layperson I'm telling you - it confused me. Surely you must know that laypeople don't refer to C as a tone. We call it a note. This may upset some people that spent years learning the difference but that is what we call it.

- I'm not going to bother mentioning the introduction of different types of scales as being not understood to any degree by laypeople.

- Then there's the third paragraph:

In the above-mentioned naming convention, a fourth is an interval encompassing four staff positions, while a fifth encompasses five staff positions (see interval number for more details).

- This means nothing at all to a layperson. I don't even know what to object to, it's that obscure. Having followed the link to the Staff article (a violation of WP:EGG BTW) I realize that you have now used three distinct terms to reference what, to the layperson, is the same thing. Believe it or not this does not make the article easier to understand.

- The sentence after that:

The augmented fourth (A4) and diminished fifth (d5) are defined as the intervals produced by widening and narrowing by one chromatic semitone the perfect fourth and fifth, respectively.

- Do you really think that someone that knows what it means to "widen" or "narrow" a perfect fifth doesn't know what a tritone is? And how does introducing the narrowing of a perfect fifth to a diminished fifth help the layperson understand the concept of tritone? (Always assuming that's what was being mentioned, I don't know)

- It's content like this that makes us complain that this article is not understood by the layperson. With obstacles like these in mind is there value in trying to edit this article for the layperson? Is this one of those exceptions that just isn't going to be understood until you understand what these other things are first? How do we note that in the article? Is there something that can be added to the heading to warn people this is a technical article and requires detailed knowledge to use? Padillah (talk) 15:32, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- Thank you for the specific examples. I immediately see a recurring problem, which is the confusion of "tone" with "note". This has got one very unfortunate aspect, which has to do with the difference between American and UK terminology ("note" in the UK is often used where Americans say "tone", and from what you say I assume you are from the UK). However, I think the problem is larger than this, and should be addressed. As for using "three distinct terms to reference what, to the layperson, is the same thing", I believe this may have been done in a desperate attempt to address exactly the problem of which you are complaining: explain one and the same thing in three different ways, in the hope that, if the first two fail to get the information across, the third one is bound to accomplish the task. I really don't know what to say about using "widen" to explain "augment", and "narrow" to explain "diminish". Perhaps a little meditation on this passage will produce some alternative that is more meaningful to the layperson. Perhaps in the end you are right: the layperson will never be able to understand such a complex and sophisticated a subject as different degrees of pitch difference.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 17:05, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- Carefully reading over the lede paragraphs, I have to admit they make my brain hurt. In addition, there is at least one statement that is flat wrong: a diatonic scale may well be said to contain only one tritone, but it is not necessarily an augmented fourth—it depends on which of the two notes you start from (e.g., in a C-major scale F up to B is an augmented fourth, but B up to F is a diminished fifth). I am also inclined to agree that all that stuff about different kinds of scales does not really belong in the lede, which should only summarize the main points. The opening sentence, however, is strictly accurate: the traditional definition of a tritone does in fact include the idea that it is composed of three whole-tone intervals, and therefore "includes" four (not three) notes. However, strict accuracy and a useful summary are not necessarily compatible, either, and the distinction between a distance and the way that distance is built up within a scale, while important to understanding musical interval terminology, is probably best delayed until later in the article. This quickly becomes way too complicated for a lede, since it entails explanations of "species" of an interval, such as whether that distance is (virtually) divided into three whole steps, or a half step (semitone, or minor second), two whole steps (whole tones, or major seconds), and another half step. Now my brain is starting to hurt again, so I will stop.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 18:51, 9 November 2012 (UTC)